Think quotas are the key to getting women into leadership roles? Think again, writes Shaheena Janjuha-Jivra

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”https://issuu.com/revistabibliodiversidad/docs/dialogue_q1_2017_full_book/32″ ]READ THE FULL GRAPHIC VERSION[/button]

Gender diversity in leadership is as big an issue as ever. Some might point to significant strides in women achieving political leadership – with Angela Merkel in Germany and Theresa May in the UK. Others may argue that the time has never been better for women aspiring to leadership roles in business.

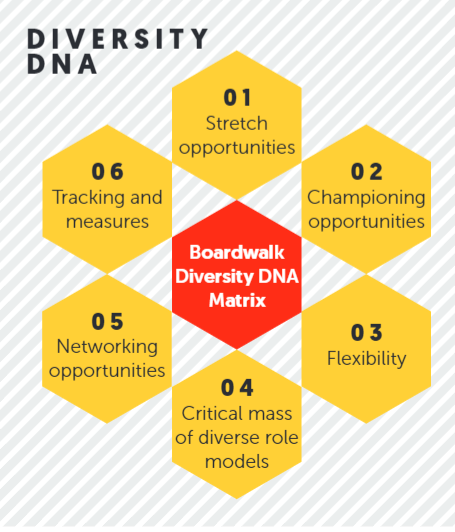

A deeper look at the profile of women in leadership roles, however, gives a very fragmented picture. The typical question clients pose has moved away from the ‘why does gender diversity matter?’ to ‘how do we achieve gender diversity and retain female talent?’. Organizations fall into the trap of using a ‘silver bullet’ approach, focusing on one or two areas: such as setting quotas or targets and flexible-working policies. They assume that if these are addressed, the challenges of getting more women into leadership will be solved. In reality, the process is far more complex and nuanced, and requires a series of connected activities combining policy, measurements and interventions to achieve sustainable behavioural change across an organization. The Boardwalk Diversity DNA Matrix (below) has been created as a result of analysis of good practice across 53 countries, examining both national policy and organization-wide practice to understand what really works in recruiting, retaining and promoting female talent. The matrix identified six key areas organizations need to focus on to create an inclusive culture and added value from a diverse workforce.

For the last decade, quotas have dominated discussions around leadership positions for women. The emotive nature of these discussions often leads to a mistaken assumption that quotas are the most effective means of achieving diversity in leadership. The dominant view has been that quotas will intrinsically breed attitudinal shifts across different sectors, resulting in the proliferation of more gender-balanced boards across all sectors. Our research on women in leadership across the 53 Commonwealth countries demonstrates this is not the case. In fact, the value of quotas as a silver bullet is strongly challenged. The data clearly demonstrates that there is no correlation between quotas and success in achieving balanced gender leadership.

The research measured women appointed to leadership positions across the private, political and public sectors. The internationally accepted baseline is 30%, the point at which a minority group will make an impact – challenging groupthink and normalized behaviour. Our research reveals which countries have reached or exceeded the 30% baseline, and in which sectors. Analysis of the data demonstrates that the successful sectors and countries do not share a common policy – including the imposition of quotas – and therefore we cannot assume success lies in the implementation of legally imposed quotas with penalties for noncompliance.

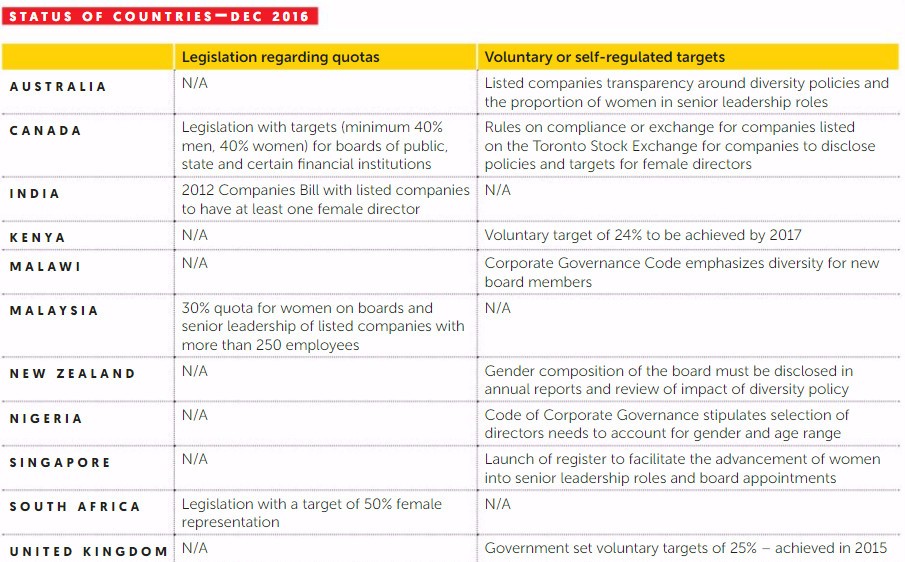

The countries with clear policies on quotas are represented in the table opposite. The table shows the broad range of legislation and voluntary procedures across different countries, reinforcing the point that there is no single remedy for the issue. Countries with hard rules on quotas have struggled with achieving targets. For example, in the case of India the initial deadline had to be pushed back as the targets were not reached, with similar experiences in South Africa.

If we look at the countries that have successfully achieved the 30% benchmark, there are alternative approaches that warrant greater attention. One of the most surprising results in this research is the prevalence of women in leadership positions in the public sector across the Caribbean (see above left). In terms of gender profile, women in the Caribbean are highly educated, with more girls than boys in education and higher attainment levels. The impact of a highly educated section of the female workforce has created a strong pipeline of talent for the public sector. The public sector is regarded as a more stable working environment, along with better conditions and pay.

Yet despite their considerable academic success, there is still gender disparity in pay, with women earning less than their male counterparts, and more women seeking jobs in the private sector. In some countries, more than 70% of leadership positions in the public sector are held by women. But, by contrast, only two states (Barbados and Dominica) have over 30% of board positions in the private sector held by women.

The education profile of women creates a strong pool of talent for recruitment. A training programme for high-potential women in the public sector was established to provide opportunities for leadership development along with collaborating with the private sector in solving real-life challenges. The interactive nature of the training programme created the opportunities to build transformational leadership skills to support working with diverse teams and create truly innovative approaches to improve the quality of life for people.

The Diversity DNA Matrix draws together the six key areas organizations can address to be better prepared for diversity and inclusion. Each of the areas are interlocking to create greater transparency around measures and progress, along with specific interventions to create promotion opportunities for women, using networking opportunities to identify talent to create championing opportunities. Policies to create more flexible working conditions also need to address how line managers implement policies in a fair and consistent manner – and that means addressing bias, both conscious and unconscious. Stretch roles create the antidote to the sticky-floor syndrome that impedes female leadership progression. When clients apply the Diversity DNA Matrix they are able to adapt each of the areas to what already exists in the organization, and this provides a powerful starting point. This approach is more likely to achieve success – because organizations do not have to react to quotas as a knee-jerk reaction that is likely to be accompanied by resentment and resistance.

Building a diverse team is the first step for many organizations. The next, more challenging goal is to create an inclusive culture. Transformational leaders have the skills to encompass diversity and mobilize the wide range of talent in their teams, yielding greater financial returns and improved leadership potential across the organization.

Dr Shaheena Janjuha-Jivraj is chief executive of Boardwalk Leadership, a training and research consultancy with global reach, specializing in gender diversity and inclusion