Chief executives need to know how to unwrap Earth’s new powerhouse

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”https://issuu.com/revistabibliodiversidad/docs/digital_book_for_issuu/28″ ]READ THE GRAPHIC VERSION[/button]

From small roads great economies grow. In the early 1990s, China was a relatively small economy that had just built its very first highway. Benefiting from IMF’s help, India had barely managed to escape bankruptcy. How the structure of the global economy has changed over the last 25 years! China is now the world’s second-largest economy, and competing with the US on all fronts – economic, technological, and geopolitical. India is today the world’s sixth-largest economy. By 2022, it will surpass Germany to become the fourth-largest and, by 2025, may even overtake Japan into third place.

Southeast Asia is another powerhouse. Home to 600 million people, the ten countries comprising the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) account for US$2 trillion in GDP, just a tad smaller than India’s and, as a region, make up the third fastest-growing economic block in the world, after China and India. By almost all measures, it can be said that this will be the Asian Century.

Other than ongoing digital disruption, nothing should be more important for Western chief executives than emerging Asian nations – because it is these economies that will play central roles in shaping Asia’s destiny over the next decade and beyond.

Making sense of Asia’s growth

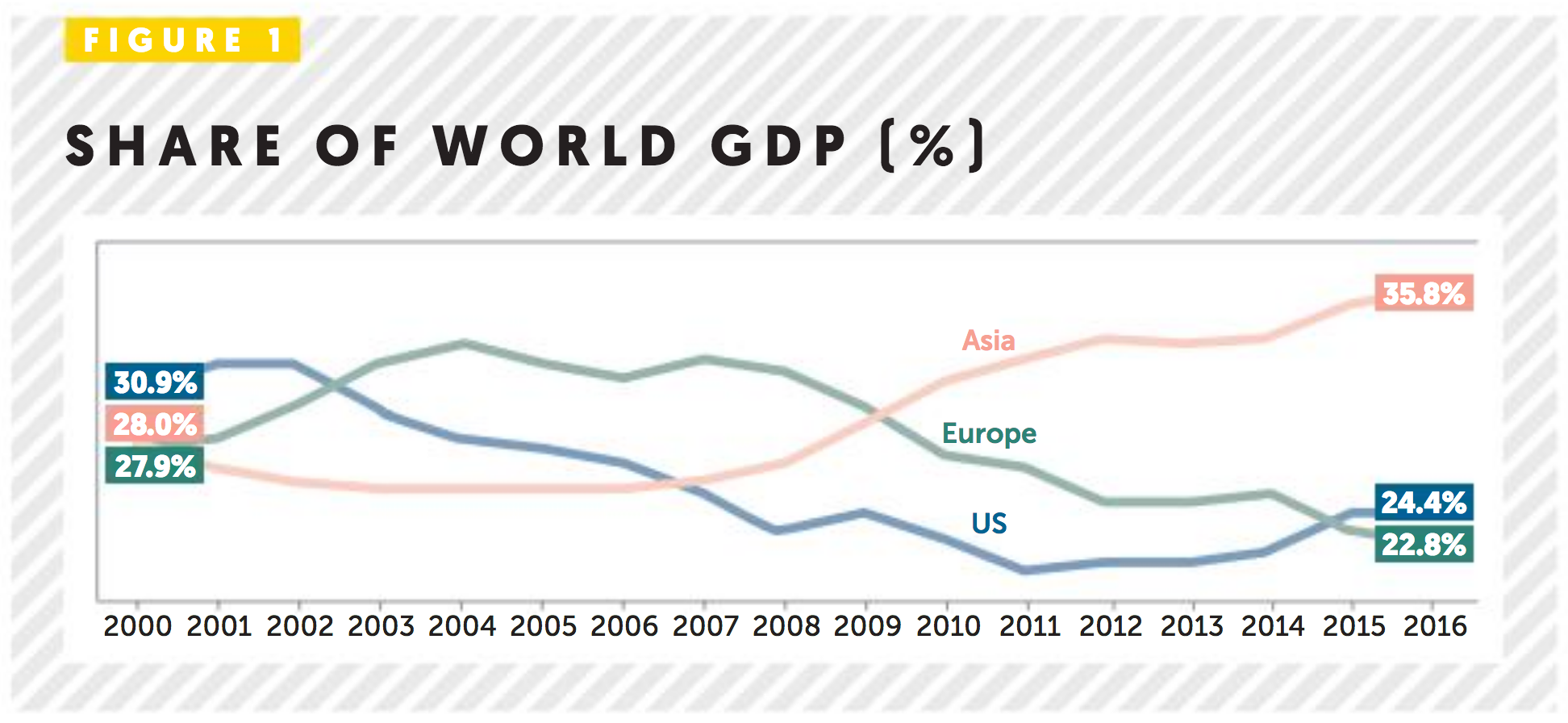

Figure 1 tracks the global GDP share of the world’s three economic legs – the US, Europe and Asia. As recently as 2000, all three legs were about equal in size, each accounting for almost 30% of the world’s GDP. In fact, at that time, the US accounted for a slightly bigger share than the other two regions. It is a very different story today. Asia is now 50% larger than the US or Europe. By 2025, Asia’s GDP will be larger than that of the US and Europe combined. In short, in a mere 25 years (2000-2025), the structure of the world economy will have changed dramatically.

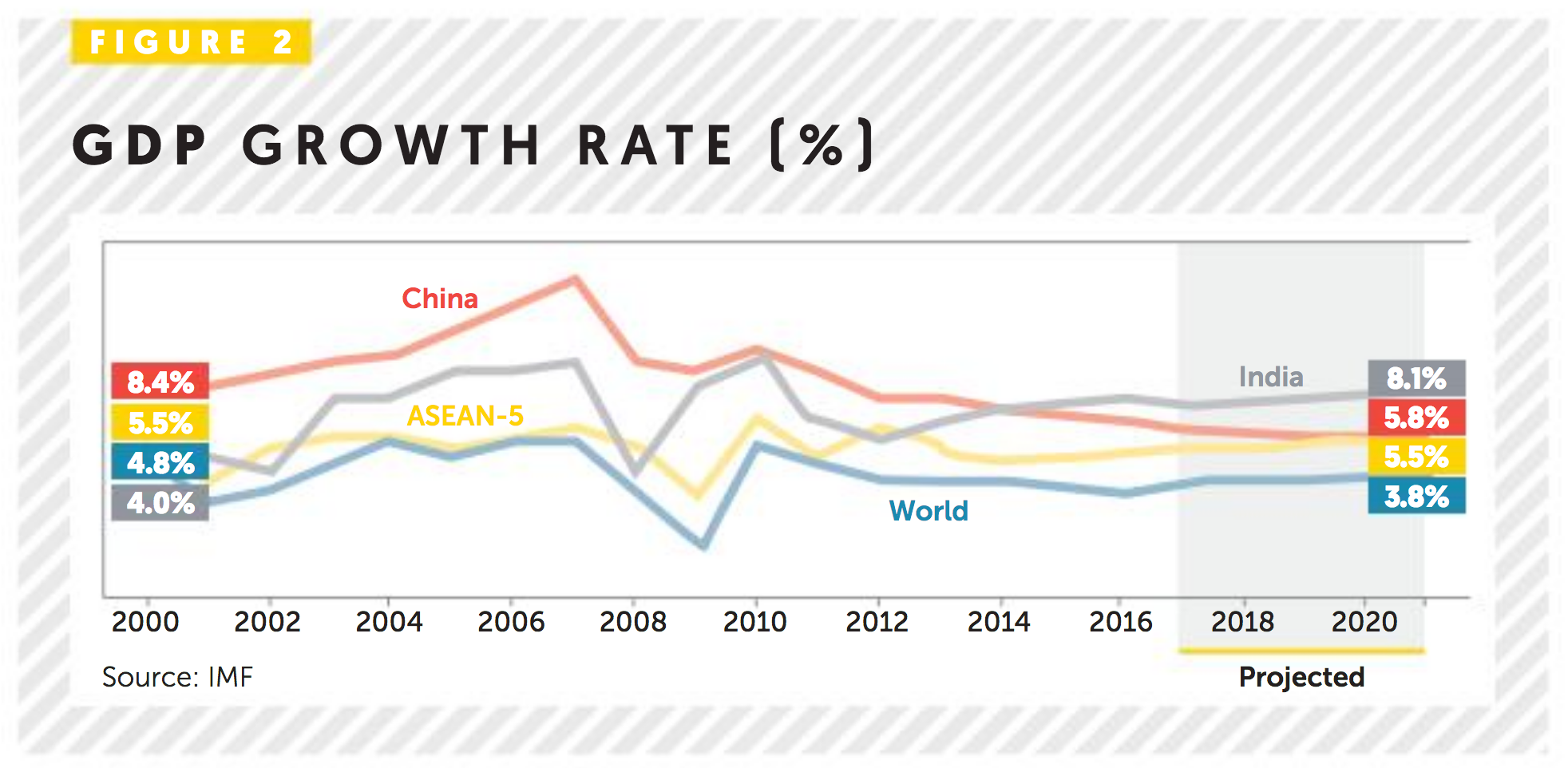

Figure 2 helps us make sense of why Asia is growing at such breakneck speed. The answer lies in the three big legs of emerging Asia – China, India, and ASEAN.

All three are growing much faster than the other big emerging markets of the world – Latin America and Africa, whose economies are growing at around 4% a year.

Asia’s advantage relative to Latin America and Africa? First, massive scale. As a result, on purely economic grounds, most of the world’s multinationals feel compelled to invest and manufacture within China, India and ASEAN rather than export to these markets. This trend brings not only capital, but also knowhow.

Second, a deep love for science, technology, mathematics and engineering (STEM). Just look at Asia’s disproportionate share of PhD students in the STEM fields in US universities. As a result, Asian economies are able to absorb foreign technology at a faster pace than in Latin America and Africa. And in terms of patents granted, China and India are the world’s two fastest-rising technology powers.

Third, political stability. Country risk is lower in Asia than in much of Latin America and Africa. Lower country risk makes both foreign and domestic companies more willing to invest for the longer-run in Asia

than elsewhere.

Fourth, very high rates of saving. As a result, Asian economies have more domestic capital available for investment in infrastructure, a foundational requirement for

economic growth.

What could hold Asia back?

- Threat 1

The middle-income trap

The biggest risk is a middle-income trap, where a country attains a certain income and gets stuck at that level. China’s per capita income has to reach only one quarter of that of the US for it to become the world’s largest economy. India’s per capita income needs to reach only one tenth of that of the US for it to become the world’s third-largest economy. In short, given their vast populations, even if China and India were to keep growing as middle-income economies, they would become economic powerhouses. Over the last 100 years, very few countries have managed to avoid a middle-income trap, the exceptions being South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Will China, India and Indonesia manage to break through? As in the case of South Korea, this will require massive structural reforms.

Asia’s fortunes also depend on how geopolitical tensions play out. North Korea, the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the China–India border, the India-Pakistan border and the Middle East are some of the world’s major geopolitical hotspots, all based in Asia. If any of these tensions morph into full-scale war, the consequences could be catastrophic.

- Threat 2

Asia becomes more ‘Asian’

Asia is becoming more internally integrated. Rapid growth means that opportunities for exports and imports among the Asian economies are growing at a faster pace than trade with the US, Europe or elsewhere. They also benefit from geographic proximity and shorter supply chains. Figure 3 aptly captures the growing intra-Asia integration via trade.

The prospects for further trade integration within Asia look promising. China, India, ASEAN, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand are currently negotiating an intra-Asia free trade agreement (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP). As and when RCEP becomes a reality, it will provide another fillip to rapid growth in intra-Asia trade.

Asian economies are also coming closer via foreign direct investment. When Chinese and Japanese giants look at big, fast-growing markets for investment, India and ASEAN loom large. Thus, it is not surprising that Chinese technology companies such as Alibaba Group and Tencent have made some of their largest – multibillion dollar – outbound investments in India and Southeast Asia. This is true also of Japanese and South Korean companies. Japanese car companies enjoy over 50% market share in India. Hyundai from South Korea is the number two carmaker in India. Samsung and LG are the two largest companies in India’s home appliance market. And Japan just launched India’s first bullet train project – the capital investment of around US$20 billion is being financed almost solely by Japanese banks.

Asia’s opportunities for multinationals

There are two important ways in which multinational corporations can leverage the rise of Asia:

- as market destinations

- as global platforms to expand the company’s reach in other markets

Evolving market opportunities in China

As China’s economic growth slows from the average of 10.5% during 1980-2010, to around 6% today, its economic structure is also changing. Sectors such as steel, cement, glass and construction machinery – whose fortunes are tied to growth in real estate and Home Additions industry– suffer from slow growth and massive overcapacity. These are no longer viable market opportunities for foreign multinationals.

The automobile sector has also slowed considerably. The days of 30+% annual growth are gone. Car sales are now growing at around 5% a year. With the ubiquitous spread of ride sharing, even this level of growth will shortly taper off. Selected opportunities do exist, however. As Chinese buyers trade up, demand is shifting from mass-market cars to luxury brands, including Tesla in electric vehicles. The real growth opportunities lie in industries that cater to new needs and wants.

- Industrial automation The driver here is a shrinking labour pool

- Solutions for energy efficiency driven by leaders’ desire to reduce China’s massive dependence on imported oil

- Solutions for pollution control and abatement Along with India, China is home to many of the most polluted cities on earth

- Solutions for agricultural productivity and water scarcity Even though China is a vast country, only one eighth of its land area is arable. China also suffers from acute scarcity of fresh water

- Business-to-business services As Chinese companies become bigger, get listed, go global and make acquisitions: they need leading-edge professional services of all types – accounting, legal, investment banking, and so on

- Business-to-consumer services High-growth opportunities exist in almost all domains – childcare, elder care, healthcare and financial services. With a very high proportion of dual-career couples, a growing number of families in China have the financial means but not the time to devote to childcare. A very high rate of savings also means that they need advice regarding how to invest money wisely instead of gambling it on speculative real-estate or ill-advised stock market investments. As the population gets rapidly older, they also need help taking care of their parents – not just in terms of health care, but also retirement homes and nursing homes

- Higher-quality goods and travel Given the ferocious clampdown on corruption, conspicuous consumption by government officials has come down dramatically. Yet, with rapidly growing affluence, millions of Chinese households are trading up in the quality of what they eat, what they wear, how they live, what type of car they drive and how they spend their free time. This may not mean more Ferraris and Porsches, but it does mean more Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi and Land Rover cars. It also means more imported food and dining out. Perhaps, most important of all, it means much more foreign travel

Evolving market opportunities in India

India is running about 13-15 years behind China, the time gap between 1978 and 1991, when China and India respectively launched their economic reforms. Thus, market opportunities in the India of 2015-2020 are, in many ways, similar to those in China during 2000-2005.

India’s biggest drive today is a rapid buildup of infrastructure. Thus, demand for all types of products and services connected to the construction sector is growing faster than the economy as a whole. This includes not just industrial products, such as construction machinery, but also consumer goods, such as home appliances.

Similar to the China of 15 years back, the car market is growing rapidly. India today is the fastest-growing car market in the world.

There are, of course, some important differences in today’s India and the China of 2000-2005. Today’s technologies are far more advanced than those of yesteryear. As a result, as India becomes increasingly urban, the government is pushing for the creation of smart cities. As solar power becomes price competitive with fossil power, coal demand is rising much more slowly than anticipated. Instead, demand for solar and wind power equipment has skyrocketed.

Similarly, on the consumer side, some of the biggest growth stories are private schools and after-school tutors for children, financial services to help people manage their savings, smartphones, social media, e-commerce, ride sharing, ready-to-cook food, dining out and travel. After China, outbound travel from India is the second fastest-growing in the world.

Leveraging China and India as global platforms

In 2013, President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with the goal of boosting China’s road and maritime connectivity with the rest of the world, most notably Asia and Eastern Europe. By some estimates, BRI could mean a capital investment of around US$1 trillion over 20 years. Companies such as GE and Honeywell are looking at the BRI as a potential opportunity to leverage their strengths in China and partnerships with Chinese companies to grow their business in the BRI countries.

India is playing a different kind of platform role. Unlike China, the Indian government makes the country far more open to foreign multinationals and does not pursue a my-market-for-your-technology policy. As a direct result, most of the world’s technology giants prefer to do leading-edge R&D work in their Indian, rather than Chinese, labs. Google has its second largest R&D lab in the world – after Silicon Valley – in India. This is true also of other technology giants, such as IBM, SAP, Adobe and Texas Instruments. Google and Facebook look at India as the ideal platform for the development of internet services that would work well with low-end smartphones, slow bandwidth speeds, and be extremely affordable. Once developed for India, these solutions can then be rolled out to other emerging markets.

Something similar is also playing out in the automobile sector. Companies such as Ford, Hyundai, and the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance now use India as the launchpad for the development and marketing of cars aimed specifically at emerging markets. The logic is that success in India can be cloned easily in other emerging markets.

Asia beckons

Asia’s GDP today is 50% larger than either the US or Europe. By 2025, it could be bigger than the US and Europe combined. Asia will still be growing faster than any other region of the world. Asia is also becoming internally more integrated – by trade as well as investment linkages. Thus, becoming smart and serious about Asia is a strategic imperative, not an option.

There exist massive and growing opportunities to benefit from the large markets for almost everything in Asia. In addition, China and India offer the potential to serve as global platforms to enter and succeed in markets outside Asia.

Two of the key requirements for success in Asia include making Asia your second home, and learning to make sense of the world, not just through Western, but also Asian, eyes.

— Anil K Gupta is the Michael D Dingman chair in strategy and entrepreneurship at the Smith School of Business, the University of Maryland and a visiting professor at INSEAD. Haiyan Wang is managing partner of the China India Institute

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”https://www.linkedin.com/groups/5125875″ ]JOIN THE CONVERSATION[/button]