The father of modern management, Peter Drucker, tells us what to do about risk, writes William A. Cohen

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”https://issuu.com/revistabibliodiversidad/docs/dialogue_q3_2016_full_book/58″ ]READ THE FULL GRAPHIC VERSION[/button]

Risk in management is unavoidable. Some of Peter Drucker’s clients did not acknowledge this. They thought risk could be avoided and wanted Drucker to show them how. But instead, Drucker told them not only was risk unavoidable, it could be desirable. In fact, the assumption that risk is present is a basic element of any successful enterprise.

Change is inevitable, risk is necessary

Drucker saw that, in attempting to lower risk, managers and professionals of all types sometimes made assumptions that could lead to disaster. The most popular method of risk lowering is to assume either no change in the current situation or that a trend, whatever it is, will continue into the future. The fallacy of either can be seen almost daily as many stock market investors make one of these assumptions with poor results. Drucker understood that change is inevitable and he advised his clients to think the same way.

Picking the right risk is crucial

Drucker learned to analyse situations and emphasized the importance of taking the right risks, because taking the wrong ones can be disastrous. Drucker’s investigations led to the discovery of a critical factor in the process: while deciding on the right risk, one must establish controls over the actions involved in taking that risk. If managers fail to do this, actions might be mismanaged and intended objectives not reached, even though the right risk has been taken. Selecting the best bet to make is useless if that bet is poorly executed.

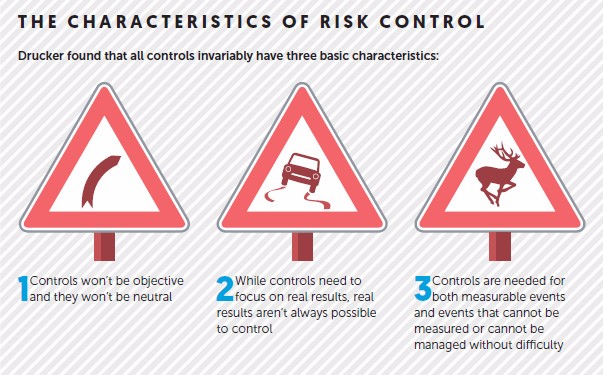

The near impossibility of objectivity

From 1924-1932 a study of lighting conditions was carried out at the Hawthorne Works, a Western Electric factory near Chicago. One experiment involved examining the effect of better lighting on productivity. It sounds simple enough. The control was based on increasing the wattage of the light bulbs weekly and then noting the results in productivity. It was expected that productivity would increase as lighting improved week on week and, sure enough, it did.

However, one week, some joker decreased lighting intensity instead of boosting it. Guess what? Productivity improved anyway. It was neither a miracle nor an error in measurement. In practice, workers had expected the lighting intensity to increase and this motivated them to work harder, more efficiently, and more productively. Today this is known today as the Hawthorne Effect. It demonstrates that the novelty of being the subject of research, along with increased attention to measuring the results, can cause at least a temporary increase in productivity. Measuring people’s actions is unlike measuring physics. “Controls are not applied to a falling stone,” said Drucker, “but to a social situation with living, breathing, human beings who can and will be influenced by the controls themselves.”

How to focus on real results

It is relatively easy to measure effort or efficiency, but much more challenging to measure real results with a control. Drucker explained that it was of no value to have the most efficient engineering department if the department was designing the wrong products. Drucker also differentiated leadership from management, saying: “Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.”

Measuring efficiency is usually less difficult. For example, one can measure the number of times a leader recognizes subordinates for accomplishing good work. That’s considered a sign of good leadership. However ‘good work’ can be done on the wrong things, as well as the right ones. Maybe salespeople are doing a marvellous job of selling the wrong products. Is this ‘good work’? To complicate controls further, how do we know what are ‘the right things’? This is much harder to know when so many factors, and multiple human beings, are involved. Since leadership is an art, an observation, its value might well be in the eyes of the beholder.

Some results cannot be measured

Controls can be challenging because some events, relevant to organizational risk, simply are not measurable. We have already noted that nobody possesses facts about the future. We cannot know what may suddenly happen. For example, the ubiquitous slide rule, once carried by every engineer worthy of the name, disappeared almost overnight when the pocket electronic calculator hit the market in the early 1970s.

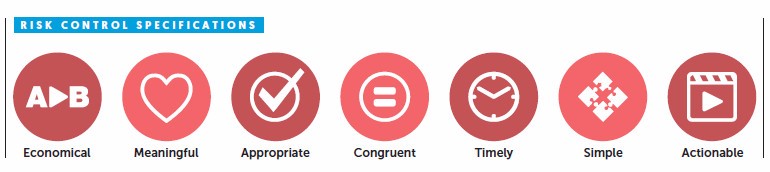

Drucker investigated further and determined that all controls must satisfy certain specific specifications (see panel, above):

- They must be economical. The less effort required to gain control, the better.

- They must be meaningful. In other words, they had to be intrinsically significant or symptoms of significant developments.

- They must be appropriate to the nature of what you are measuring. Absenteeism of a yearly average of ten days per employee sounds acceptable, but what if you have only two employees and one was never absent and the other recorded 20 absent days?

- Measurements must be congruent to the phenomenon measured. As a writer, I’m interested in book sales. I once read a bestselling book by a famous entrepreneur. He had bought a well-known company and promoted the company’s product frequently on television stating, “he liked the product so much, he bought the company”. His advertising promotions were great. However, when I read the book, I found it was, at best, fair. Yet it sold 2 million copies, surpassing many better books about entrepreneurship in sales, including Drucker’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship, which came out at about the same time (not to mention several that I had written, the best of which sold just under 100,000 copies).

One day it was revealed that the author had spent almost $2m of his own money promoting his book. Book royalties are a lot lower than you might think, frequently around 15% of the net total received by the publisher – itself often only half of the retail price of the book. Since this entrepreneur was not the publisher, I estimated that he earned approximately $1m in royalties from his total book sales, which amounted to a personal loss of $1m. Of course, he may have been willing to pay this to have had a bestseller, just for bragging rights. But it demonstrates that, as a control measurement, book sales alone – the tool most frequently used to measure public demand for a particular book – is deeply flawed without other factors being noted and compared.

Control requirements 5, 6, and 7 are much easier to grasp, and more intuitive. Controls need to be timely. They are an expensive waste of time if the information received arrives too late to be of use. They need to be simple. As Drucker noted, complicated controls don’t work. They frequently cause confusion and lead to other errors. Finally, controls need to be orientated towards action. Controls are not created for academic interest. They are for implementing strategy once actions, which involve the right risks, have been chosen.

The final limitation

The final limiting factor for controls is the organization itself. An organization operates with rules, policies, rewards, punishments, incentives and resources, capital equipment and so forth, but its success comes from people and their daily, frequently unquantifiable, actions. The expressions of their actions, such as an increase in salary, may be quantifiable. However, their feelings, motivations, illnesses, drive, ambitions and the like are not. As an operational system, the organization cannot be quantified accurately.

What it all means

Risk is essential. The key to success is picking the right risks and then controlling these risks, taking into account the many factors that make controls so difficult to comprehend and use. But knowledge is power. Selecting the right risks, and monitoring the seven important aspects of the risk controls identified by Drucker, leads to effective risk management. One cannot do more, nor should the consultant consider doing less.

This article is adapted from Peter Drucker’s Consulting Principles, to be published by LID Publishing in 2016