Businesses’ lifespans are getting shorter – but 12 habits can help leaders buck the trend and create great, enduring organizations.

Startups rarely survive their second birthday. Even established UK and US firms now only live for 15 years. How can your organization buck this trend?

This question ignited a 13-year study to try to understand why so many businesses are dying, the beliefs and behaviors behind the high failure rate, and how we could do things differently.

To do this, we first identified seven ‘Centennials’ who have outperformed their peers and endured for over 100 years. In sport, we looked at the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team and British Cycling; in education, Eton College; in science, NASA; and in the arts, we looked at the Royal Academy of Music, the Royal College of Art and the Royal Shakespeare Company. We spent five years working with those organizations to see how they worked from the inside, before exploring their beliefs and behaviors with 500 business leaders. Finally, we analyzed the neuroscience and psychology behind what we had established were the wrong behaviors for longevity, to see how we could break them.

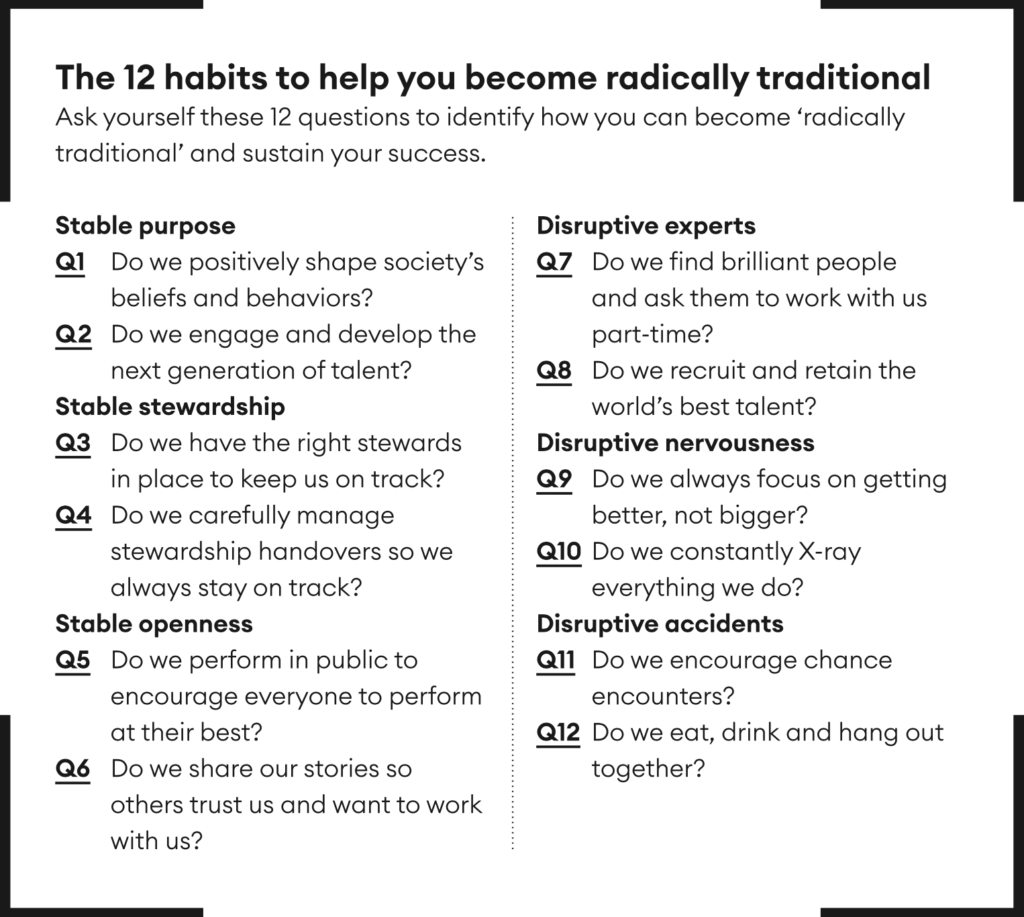

Our findings surprised us – and everyone we met. The Centennials don’t focus on growth, cost and being secretive, like most organizations. Instead, they try to get better, not bigger. They are intentionally inefficient, and they share their stories with the world. They’re “radically traditional”, as the Royal College of Art puts it. They build a stable core – built on purpose, stewardship and openness – and a disruptive edge, which is maintained via experts, nervousness and accidents. That combination is what keeps them ahead.

Stable core

For long-term success, the first question to ask is: “What is our North Star? What are the beliefs and behaviors we want to shape in society over the next 20 or 30 years?” If you don’t do this, at some point, all your money and talent will start to go elsewhere.Take the computer science industry. It’s struggling to attract the talent it needs – particularly women – as it tries to continue to change the world. As a result, we live in world that is often designed by men, for men; where, for example, Alexa can struggle to understand female voices, mobile phones are often too big for women to hold, and AI has helped develop medicines and cars that are often more dangerous for women to use.

This is not only a huge problem for society, it’s a huge problem for the companies involved: if they aren’t able to attract more women in future, they won’t survive. But it wasn’t always like this. Some of the first computer scientists, at Bletchley Park in the 1940s and NASA in the 1960s, were female. By 1985, half of the computer science graduates in the US were women.

But in the mid-80s, everything changed. Personal computers came out and were targeted at boys. Parents put them in their sons’ bedrooms, where their daughters couldn’t get to them. The industry produced games that were made for boys, films that were made about boys, and helped set up school clubs – for boys. As a result, between 1985 and 1990, the number of female computer science graduates more than halved, falling from 15,000 to 7,000 each year. The situation hasn’t really improved since.

This type of talent imbalance is not unique to the computer industry. It’s the sort of problem that can arise for any industry, or company, if it takes a short-term view and ignores its long-term purpose. Just look at the S&P 500, the index of the most valuable companies in the US. Over the last 50 years, indexed firms have become better and better at making short-term profit. Their collective market value has increased 14-fold; shareholders have profited handsomely. But, by focusing on the short-term and ignoring long-term purpose, businesses have failed to attract the next generation of money and talent. The result? The average lifespan of S&P 500 companies – their tenure on the index – has fallen to just 15 years.

Some would argue this is a good thing. When a company fails, they say, its resources can be reallocated to a better firm. However, this ignores the friction and wastage that corporate death involves. The long-term success of any economy or society depends on the stability of its core institutions – and the long-term challenges that societies face (such as education, health, immigration and climate change) are less likely to be addressed if everyone is solely focused on the here and now. A recent McKinsey study, for example, showed that if more US companies took a long-term view, they would have performed better for longer – while US GDP would have increased by over $1 trillion and there would have been five million more jobs in the last 15 years.

Three things stand out in how the Centennials maintain a stable core.

1 Purpose

The Centennials know they need to take a long-term view if they want to survive. They clearly articulate their ‘North Star’ to embody the beliefs and behaviors they want to create in society, and analyze everything they do to ensure it serves that purpose. As a result, they are confident that money and talent will be there when they need it in the future. Just look at NASA: astronaut applications have quadrupled in the last 20 years, from 3,000 to 12,000. And of the 20 astronauts it has taken on in the last ten years – twelve in 2017 and eight in 2013 – half have been women.

2 Stewardship

Once you know your long-term purpose, the next step is to check you’ve got the right stewards. These are the ‘parents’ of the organization, who set the tone and make sure the right beliefs and behaviors are passed on from one generation to the next. Typically, they’re around a quarter of the people in the organization, evenly spread from the top to the bottom and across all of its communities. For every long-serving chief executive at the New Zealand All Blacks, for example, there will be a long-serving coach, and probably a long-serving captain or other leader among the players.

Stewards normally work in the organization for at least four years before they are appointed into these key roles, and stay in post for at least ten years. There is often a two-year handover between stewards – a new leader might be announced two years before they take over, or the old one could stay on in a non-executive role. Think of how previous chief executives or chairs at Apple, Amazon and Google have stayed on after a new post-holder was appointed.

3 Openness

With purpose and stewardship in place, the final step is to check that you’re also being open. If you want to perform at your best, you need to perform in public – so the Centennials ask ‘strangers’ to watch them and help them find new ways to improve. Show others what you’re doing, and why, so they can trust you and support you.

For example, when Pixar first started out, it had a choice. It was in a race to make the first computer-animated film, and Pixar’s leaders knew they could either hold their cards close to their chest and keep their secrets, or share their discoveries with the world. They chose the latter and found that, as a result, more money and talent came to them.

Disruptive edge

When you know the core is stable, then you need to look at your edge. It doesn’t matter how stable you are: if you don’t keep moving forward, you’ll die.

3M, for example, developed a ‘vitality index’ to help it work out if it is moving forward and how likely it is to survive. It measures the percentage of this year’s sales that come from products developed in the last two years. 3M sets targets for each market, depending on how quickly it moves. In mobile phones, for example, the target would be 100%, as most people change their phone every two years. For computers it would be 50%, as these are changed every four years. 3M has built a clear understanding of how quickly it needs to move forward to survive.

Blackberry’s collapse shows how quickly things can go wrong if you don’t move forward. In the four years after the launch of Apple’s iPhone, Blackberry’s sales went up six-fold. It dismissed the threat posed by Apple and Samsung, and celebrated rising sales of its old products in new markets, such as India and the Middle East, where network speeds were slower and people couldn’t afford to buy an iPhone. But it didn’t realize that its vitality index was falling. After four years, when its old products died, its sales fell by 90% – from $20 billion to $2 billion – in less than five years.

This may seem like a freak event, but it’s not. Many companies have their best year ever right before they go under: think of Chrysler, General Motors, Kodak, Hewlett-Packard, Lucent, Nokia, Motorola and Texaco. As sales grow, their vitality index declines.

The Centennials, by contrast, take a very different approach. They know they need to keep moving forward so they are continually disrupting themselves and making changes. There are three key aspects.

1 Experts

Centennials excel at making themselves porous. To steer away from confirmation bias, to keep new ideas flowing, and to pinpoint best practice and approaches, they turn to disruptive outsiders and experts who question and challenge everything. They find the best people they can and ask them to come on board part-time: that makes it easier to say ‘yes’, and allows the experts to keep working in other fields, drawing on fresh ideas. Alternatively, experts are employed full-time – and deployed across at least three projects at once, to maximize their impact.

2 Nervousness

For most enterprises, growth is the reason they exist. For Centennials, it is something to be cautious – even nervous – about. While they know they need to be big enough to create impact and to be financially stable, they worry that growth often occurs at the expense of standards, can distract from core purpose, and can lead to a loss of control.

The emphasis is on getting better, not bigger. They often limit the size of the organization and its sites, typically with 150 people per site at most, while limiting management layers to fewer than five. And if rapid growth is essential, they set up spin-offs.

3 Accidents

Centennials make time for serendipity: they encourage happy accidents by promoting happenstance connections. To do this, they get people to work on at least two different projects, across different teams, to increase their exposure to others, and change teams regularly. They place cafes and meeting rooms in central areas so people bump into each other.

Failure, recovery and sustained success

The approaches developed by the Centennials do not exclude the possibility of mistakes and shocks. All the organizations we worked with have had a major failure at some point in their 100-year-plus existence. But the response has always been the same: go back to the core to check it’s stable and on track, and then start to look at the edge. So ask yourself: Have we strayed from our purpose, do we have the right stewards in place, and does society trust us? And then: How can we bring in better experts, how can we become better, and how can we create more accidents?

For sustained success, the lessons of these 100-year organizations is clear. First, make sure a stable core is in place – and then work on your disruptive edge.

Alex Hill is professor of operations management at Kingston University, a Duke CE educator, and author of Centennials: The 12 Habits of Great, Enduring Organisations.