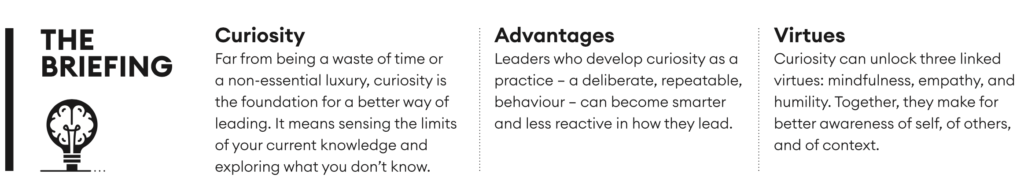

A willingness to explore what you don’t know is the foundation for leading more effectively

In theory, curiosity is an essential leadership behaviour. We lionize the Steve Jobs and Thomas Edisons of the world. The business journals regularly proclaim curiosity’s value. But in practice, who has time? Sure, we can perhaps let the folk in R&D or marketing indulge their curiosity every now and then. But the rest of us? We’ve got strategies to implement, KPs to I, Os to KR, and oh so much email. Who has time for curiosity? And, quite frankly, would it even be worth it if we did?

The wellspring

If you equate curiosity to dandy-ish meandering through fields of irrelevance, combined with dereliction of your stuff-to-do duties, then of course it’s not worth it. It’s a short road to be invited to “go be curious” in an different organization.

But curiosity should be thought of differently, as more tangible and more constrained. In its essence it’s sensing the limits of your current knowledge and being willing to explore what you don’t know just a little longer. In practice, that means knowing that the first thing which occurs to you is unlikely to be the best thing; that one of the hardest things to do is to uncover the real challenge; that a slight pause before commitment will allow other options to emerge; and that being able to make good decisions begins with understanding alternatives and options.

Things get even more interesting when you come to realize that by making curiosity a practice – a deliberate behaviour that’s repeatable – it becomes a source of three essential leadership virtues: empathy, mindfulness and humility. All three are well-known concepts; none are immediately associated with hard-driving business success. However, they can be the foundation for a new, more effective style of leadership. Each gives you an opportunity to be smarter and less reactive in any situation. Each virtue can be built through the practice of asking a good question (questions I’ll share with you). And when these three virtues of mindfulness, empathy and humility combine, something magical happens. Each feeds the others, creates a virtuous circle, and helps you change the way you lead forever.

Mindfulness (but not how you’re thinking about it)

Like coaching some 30 years ago, an obsession with mindfulness has blossomed in the fertile fields of California. Were I to ask you about mindfulness, you’d probably have both a definition and an opinion: probably something like “be here now” (definition) and “slightly sceptical” (opinion).

A definition that can reframe and, if needed, destigmatize mindfulness might be simply, “Being more situationally aware.” You’re better able to see what’s happening. You’re able to separate data from judgment, fact from opinion. You’re less limited by your assorted cognitive biases. If you can also “follow your breath” while sitting on a cushion, consider that an added bonus.

The question you can ask yourself and others on a daily basis to help make mindfulness an everyday practice is, “What do I know to be true?” It’s almost impossible to have a fast or a glib answer to this. It puts the focus in two places. Externally, it starts the process of winnowing data, separate from the interpretation of that data. That’s a revealing exercise, as it’s almost always true that a very small amount of data can generate vast amounts of opinion that can both trigger and confirm your biases.

Internally, it helps you acknowledge your subjective reality. It can help you identify how you’re feeling (“It’s true that I’m sad and I’m angry”) and also gain a meta-understanding of your own judgments (“It’s true that my opinion is that my boss is crazy”). That labelling de-escalates the power of both the feelings and the judgments. When you’re more able to see what is true, and your opinion about what’s true, your decisions are likely to be more robust.

Empathy (but not in that touchy-feely way)

The old joke suggests that if you want to understand your enemy, walk a mile in their shoes. Because then you’ll be a mile away from them. And you’ll have their shoes.

It’s also true that the ability to “walk a mile in their shoes” is one of the most common definitions of empathy. A similar but different definition is “being more other-aware”. Empathy is how you connect with the other person across from you. It’s the act of seeing them fully, being present to who they are, and having that awareness then influence the way you respond to the world.

It’s easy to not have that connection in our lives. The combination of our neurobiology, our busy-ness, the nature of our organizations and even the nature of capitalism can lead us to default to seeing the other person as a role, a tool, a cog in the machine. You harden your heart so you can get things done.

An everyday question that can disrupt that pervasive ossification is one that can be asked at the end of any conversation, whether that’s a formal check-in or an informal chat. “What needs to be said that hasn’t been said?” invites those issues that live on the margins into the centre of the conversation. It can be the small stuff – the tiny irritants where the usual thing to do is swallow the annoyance and carry on with the relationship just slightly dinged. It can be the big things – those that are laden with significance, where it’s never quite the right time to bring it up. Most importantly, it’s a question asked of, and answered by, both people in the conversation. It’s an exchange, a mutual act of vulnerability that allows empathy to take root.

Humility (but not the thinly-disguised boasting type)

Humility is often connected with a sense of abasement, of lowering yourself. That’s understandable when you realize that the etymology of the word traces back to the Latin adjective humilis, which can be translated as “from the earth” and is derived from humus, meaning “earth”.

In these topsy-turvy days, “I’m humbled” has also come to be shorthand for “I’m awesome and I fully deserve this award you’re giving me, and probably more”. But assuming you’re not yet a pro athlete or movie star, a more helpful definition for humility is “being more self-aware”.

The twist here is that this definition embraces not only what you’re less good at, but also your strengths. It in fact acknowledges all of you, in your complicated, brilliant messiness. That’s what “grounded” means: you’ve got both feet on the ground, you know who you are, and where and how you stand.

It’s only through doing this work that you can get to CS Lewis’s insight that “humility is not thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking of yourself less.” You’re only able to think of yourself less when you’ve done the work to accept yourself, and are less likely to be hijacked by the need to prove your strengths or disguise your weaknesses.

The everyday question that you can ask yourself and that can keep you grounded is, “Who am I at my best?” It’s not a question you’d typically associate with a sense of humility. But it invites the person not just to remember and acknowledge their strengths, whatever they may be, but also those attributes that contribute to better relationships: generosity, tolerance, openness to possibilities, love.

This is illuminating

In this time of pandemic and remote working, we’re all rapidly learning what it takes to show up well in virtual meetings. A good microphone. The kids in another room. Bathing at least once a week, whether you need it or not.

Also essential is lighting. The secret of going from good to great is three-point lighting. You have a key light: its job is as the principal illuminator and it is the first step in helping you be seen. Then there’s the fill light: its job is to eliminate the shadows that the key light creates. It’s typically off to the other side of the key light, and helps you be seen as fully rounded. Finally, there’s the backlight, which does two things. It reveals the background, while at the same time helping you stand out and apart from it.

The combination of mindfulness, empathy and humility is the three-point lighting of effective leadership. Humility – being more self-aware – is of course the key light. Step into the spotlight. Show us your best side. Let us see your strengths. Empathy, being more other-aware, is the fill light. You see them, and you see yourself reflected in them. And mindfulness, more situationally aware, is the backlight. We better see the context, and, at the same time, we see how we’re separate from it.

As with most things, the real power of these three attributes lies less in what they offer by themselves, and more in how they interact with each other. Each virtue has potential blind spots, or shadows, for which the other two virtues fill in and compensate.

The danger of mindfulness’s heartless focus on “just the facts” is countered by empathy and humility. The risk of empathy’s self-sacrificing “rescuer” focus is restrained by the grounding of mindfulness and humility. The possibility of humility’s self-absorption is shaken off by the pull of empathy and mindfulness.

Curiosity is a superpower

Curiosity is the foundation practice. By engaging in curiosity as a repeatable, deliberate behaviour, the three virtues of mindfulness, empathy and humility emerge. They are the pathways to smarter perception and action. By being more situationally, other- and self-aware, you start to better triangulate reality.

Laying down the gauntlet and challenging people to “Be more mindful! More empathetic! More humble!” feels overwhelming and is not obviously accessible. Shifting the focus to curiosity can make it feel more achievable. So stay curious a little longer. Avoid the “advice trap” of defaulting to the habitual responses of “I know…”, “Let me tell you…” and “Can I suggest…” Ask the questions that open the possibilities of deeper insight, clarity of focus, and even personal transformation.

Stay curious and you will change the way you lead forever.