In the wake of coronavirus, understanding the behavioural levers of progress is more critical than ever

Humanity was underperforming before the virus. The gap between where we were and where we could be was a gulf prior to the pandemic’s arrival. How will it look after Covid-19? It will mostly be worse, but it will also force us to work harder and make some changes.

On public healthcare, human safety, and economic management, humans’ potential is far higher than our performance. So what are the behavioural elements that limit our progress? What levers should we use to move forward more effortlessly? What interventions would have the most profound impact? Where and on what should leaders and lawmakers focus their efforts and resources?

To answer these questions, we should consider for a moment that changing behaviour is the same as launching a space rocket. There are two fundamentals that determine this craft’s chances of success.

The first fundamental is friction. The more scientists and engineers are able to reduce friction, minimizing drag on the spacecraft, the better its progress into the cosmos.

The second fundamental is motivation. Its fuel-carrying capacity is critical. The efficiency at which it converts its fuel via combustion into kinetic energy is another critical element.

Space flight is determined by the relationship between friction and fuel (motivation). If the friction outweighs motivation, the rocket remains on the ground. If the motivation outweighs friction, it shoots to the skies. Human progress is determined by the same levers.

The personal finance paradox

How do you help people who struggle to manage their money? When asked this question, most folks – quite reasonably – suggest teaching people the ABCs of money management.

But here’s the thing. Teaching people about money management doesn’t work very well. In fact, it’s a really poor way of having them improve their handling of their personal finances.

Our memories are blameless here. Personal finance tutees remember the lessons perfectly well. The problem is they don’t execute them. Even immediately after learning the techniques to manage their money, only 4% of course attendees put the techniques into action. In the medium-term that figure falls to a statistical zero. Only 0.1% of tutees maintain the habits beyond a few weeks of their learning them.

The right medicine

If telling people doesn’t work, what does? It turns out that reducing friction really works. There is a story about an online pharmacy in the United States. Patients with long-term health conditions pay a quarterly fee and have their prescriptions delivered to their front door every 90 days.

The challenge is that most of the patients are buying branded drugs. Yet there are generic meds available of precisely the same formulation. They are chemically identical to the branded version. But they are vastly cheaper.

The online pharmacy wants its customers to switch to generic drugs which are higher margin for the retailer but far lower consumer cost. “It’s cheaper for you,” it says, “because it’s cheaper for us.” It decides on a campaign to have its customers switch their orders. It puts banners on its website advertising the potential savings. It sends them letters. It promotes the offer via email alerts. The case is compelling: you get exactly the same product for a third of the price.

And what happens? Nothing happens. Almost nobody switches. The customers know switching will save them money for exactly the same service. Yet they don’t switch. Telling them just doesn’t work.

Here, we need to dive into behavioural economics. Readers may be familiar with my papers on the ‘allure of free’. The evidence shows that a reduction to free is much more powerful than a drastic price cut. If you reduce a dollar soda to 40¢, then sure, some people buy it who would normally have declined, but the increase in sales is almost never commensurate to the reduction in price. If you make it free, nearly everyone grabs a can.

So what does the pharmacy do? It offers its customers a whole year of free drugs, as long as they sign over their subscription to generic brands. You might think most would switch: not only do they get the same drugs much cheaper, for 12 months they get them for nothing at all. And yet, less than 10% switch. The pharmacists – angry that the behavioural economics doesn’t work as they hoped– start writing to me. “We read about your ‘allure of free’,” they say. “Well, we made it free and they still didn’t take it.”

“Ah,” I say, “then maybe it’s about friction. They are currently buying branded and to switch to generic they still have to do something. They have to return the letter.”

The pharmacy launches a new plan. Instead of sending a letter asking them to sign to switch, it mails a letter saying that if they don’t return it signed, they will be switched automatically.

What happens? Lawyers happen! Lawyers happen in a big way. It turns out this is illegal. Illegal things are fine as hypothetical theories. They are not fine in reality. But nevertheless, the change in approach demonstrates the purity of the idea.

What did the pharmacy do? It created a T-intersection. It wrote to its customers telling them that unless they returned the letter they would lose all their medication.

If they wrote back, they had a choice: the costlier branded medication, or the cheaper generic drugs. In both cases, they had to do something. In this case, the vast majority switched. Once denied the ‘no-action benefit’ of doing nothing at all, the patients changed their behaviour and almost all of them opted for the generic drugs.

It’s the story of friction: people just don’t like returning letters.

To save a shilling

How do you motivate someone to save? There’s not much point telling people to save money. Most folks know they should put something aside for a rainy day; but they still don’t do it. Coronavirus was a crisis that few could have predicted. It hit the Western world like a hammer blow, though having personal savings mitigated the worst for most people.

But in poor countries, every day can be a crisis. Saving just a little a day can mean the difference between life and death. People are living hand to mouth, and then something happens and they have nothing to fall back on. So they borrow, sometimes at interest rates of 10% a week. Once they get into this cycle they become stuck in it – all their cash goes into repaying the interest and things get worse and worse.

Out in Kenya, the goal was to find a system that actually propelled people to save, rather than simply accept it was a good idea, but not act on it.

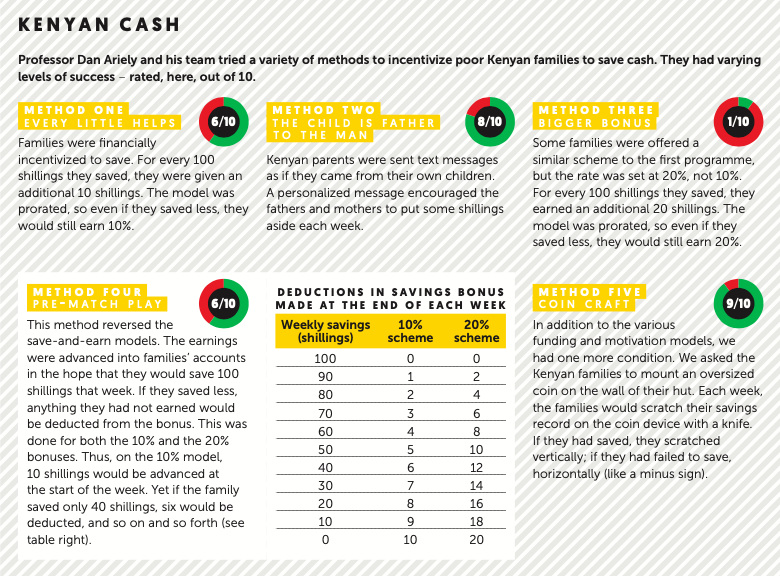

Central to the plan was the aim of incentivizing families to save 100 shillings a week – about one US dollar – so they would have something left for a rainy day. We tried all sorts of options.

Which of these methods worked best? Most people assume that the 20% savings bonus will have the most effect; the 10% bonus the next best effect; and loss aversion a small effect. The average assumption is that the children’s messages and the coin device will achieve nothing. Simply put, most people assume other people are rational actors – that increasing the incentive will deliver a commensurate increase in benefit.

But people are not rational actors. The bonus schemes had an effect, but there was no difference in savings performance between the 10% version and the 20% model, despite the rewards being double in the latter.

The loss aversion model did work – humans are hardwired to avoid loss over seeking gain. When families saw the money leave their accounts at the end of each week, it proved a powerful motivator to stop the perceived ‘loss’– despite the fact that the net result was identical to the normal schemes, in which the bonus was paid retrospectively.

So what of the text messages? It turns out that sending texts in children’s names helps a lot. The motivation was twofold. The texts acted as a reminder, and reminders are important: it’s easy to forget to save. Moreover, the emotional element of having their children asking them provided a powerful motivator: most parents worry more about their offspring than themselves. They want the best for their children, which meant that we involved their children more frequently as a motivational tool.

Yet by far the most important measure was the coin device. It doubled savings compared to everything else. But why? An experience on the other side of Africa holds the clue.

Unhiding the hidden

There is a complex city in South Africa called Soweto, and in it there is a very large slum. One day, I found myself in the slum at the sales office of a company that sells funeral insurance. To understand the importance of this you need to know that South Africans spend more on their funerals than they do on their weddings. I want to point out that that’s probably a very rational allocation of resources, given that with funerals we know for sure that we will have only one!

When I’m there, a man comes in with his son to buy funeral insurance. But he buys that insurance just for one week – it is all he can afford. If he dies in the next week, 90% of the costs of his funeral are covered. But if he survives, that money goes straight out of the family budget for that week.

Just after he purchases the insurance, the man ceremoniously places the certificate in the hands of his son. Why the ceremony? The explanation is the same as for the Kenyan coin. Buying insurance, like savings, is an observable behaviour. The only observable thing when someone saves, pays off debt or buys insurance is that there is less: less water, less fruit, fewer things on the dinner table. But by grandly offering the certificate to one’s son – like scratching vertically in the Kenyan experiment – we are demonstrating something very important for motivation: activity. We are making desirable, but invisible, economic acts visible.

Power up

Let’s return to our launchpad. Following the pandemic, the rocket of the human race needs to fly a good deal further than it would have done before. But, we can still work to bridge the gap. To do so, we must both reduce friction and provide motivation. And we must experiment to better understand what motivations will work best.

The good news is that if we hold in our minds those two key factors, friction and motivation, and if we keep testing and trying, we will raise the rocket eventually.