Haste often leads to wrong decisions. If you want to get things right, don’t rush.

Imagine you are the benefits manager in your company. You receive an offer from a local bakery to supply sugar-free plant-based pastries for consumption by your organization’s employees when they are in the office. You know that employees often reach for less-healthy snacks to kill their hunger, such as doughnuts or biscuits that contain high doses of sugar and saturated fats. What would be your reaction to the proposal?

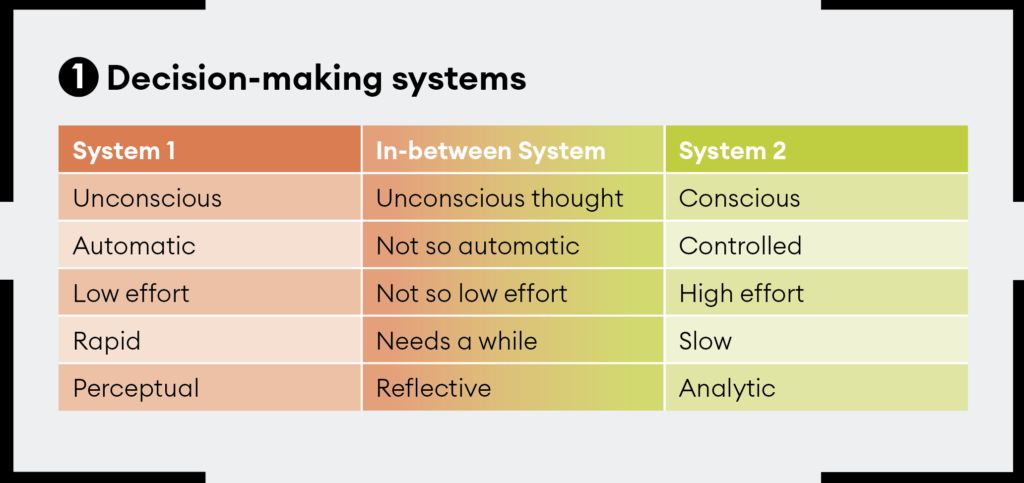

Following the “dual theory of thinking” popularized by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman in his famous 2011 book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, you could take two alternative paths: follow

System 1 and respond quickly, or System 2, and respond slowly. Let’s look at the mechanics of each system as applied to the case.

Quick vs slow response

What happens when you use System 1? Your mind makes a decision based on your previous similar experiences, the information available, your values and prejudices, and your personal situation at the time. You may have heard of another company that tried to innovate its employee benefits, with poor results. You may not know the nutritional composition of a typical doughnut compared with the proposed sugar-free plant-based pastry, or the effect of excess saturated fat and sugar on employee performance. You may not follow the recommended patterns of healthy eating and living yourself. And you may feel under pressure to decide quickly, as your next meeting is about to start. So, when you receive the offer of these alternative products, you decide not to waste your valuable time analysing the pros and cons. Your decision is to reject the proposal without even considering its possible advantages.

What happened? In this case, heuristics took over the decision process. You preferred not to spend resources on studying the case and your mind identified some reasons that seemed compelling. You felt confident enough to make a quick decision without needing to acquire more knowledge or devote more thought to the matter.

Let’s take the alternative approach: System 2. You consider that the bakery’s proposal deserves analysis because of its innovative nature and its possible benefits for employees’ health. You study the type of products that colleagues are accustomed to consuming in the office, the frequency with which they eat them, the best and worst ingredients for their performance, and evaluate the bakeries in the vicinity, as well as the range of healthy products available online. You also consult a nutritional advisor to get an expert point of view. You then go to your employee representatives and discuss with them the possibility of including healthy snacks in the company’s benefits programme. You also talk to your boss to inform him or her about your project. The problem is that while the staff representatives are willing to help you choose the best option, your boss does not seem at all happy with the initiative due to current budgetary constraints. The decision gets complicated.

What has happened now? You have assessed the decision as important and undertaken a thorough analysis process, including the involvement of other stakeholders. But you overlooked a critical factor that might have suggested it was not the right time to start the project: the resources available to fund the programme.

By using System 1, you invested no effort but missed out on the potential benefits of the proposal, while by following System 2, you have spent a considerable amount of time reaching a dead end. Could there be another way?

The In-between System

For my book The Wrong Manager, I conducted a survey of managers and executives. The first thing I asked them was to give an example of a management mistake they had witnessed. Two questions were particularly significant. One asked, “How do you think the decision in your example was made?” The most common answer, for 41% of respondents, was that the decision had been made “after a short period of reflection”. Beyond that group, 35% said that it happened “after a thorough process of analysis”, while 24% chose “quickly, once the decision maker understands the situation”.

In another question, I asked: “How do you think most of the important decisions of an organization are actually made?” Almost half, 49% of the respondents, answered that most of the important decisions are made “after a short period of reflection”. It was again the most common answer. Similarly, 36% picked “after a thorough process of analysis” and 15% chose “quickly, once the decision maker understands the situation”.

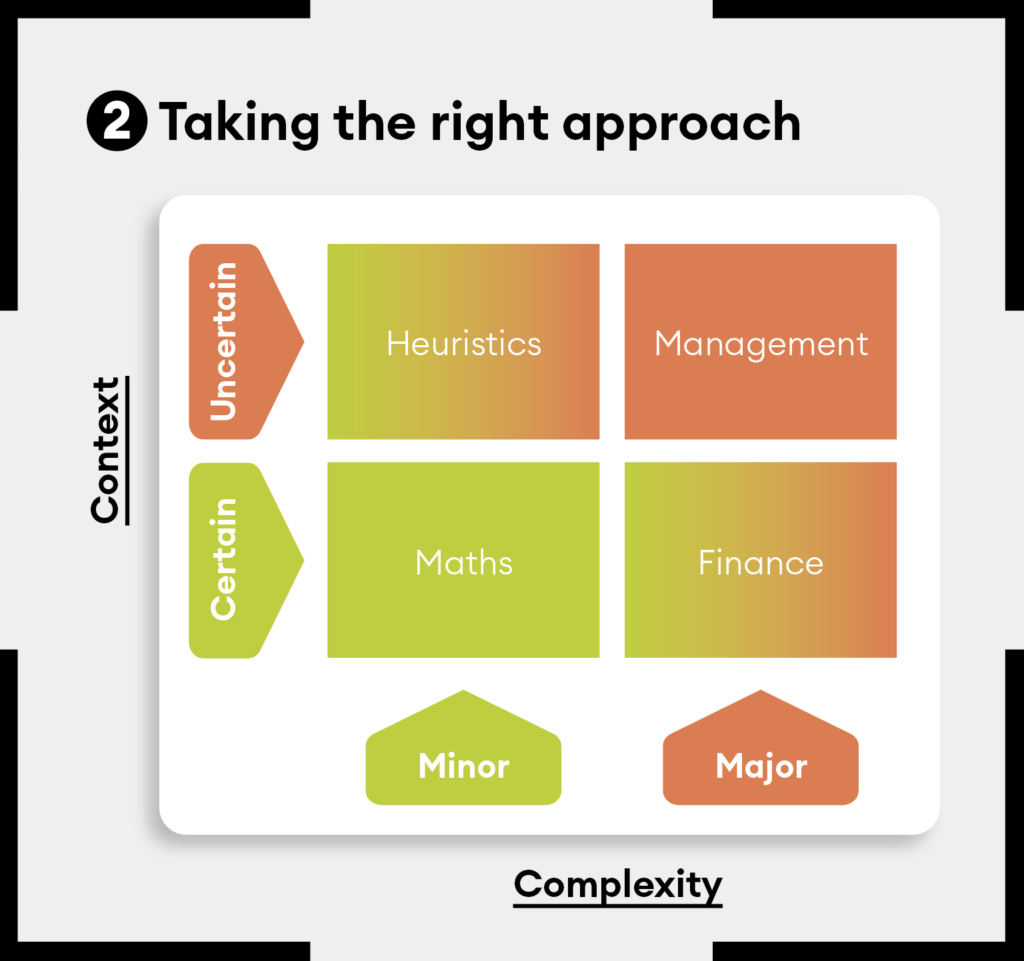

The survey seems to confirm that the most frequent position from which a manager makes a decision is somewhere in between the two systems of Kahneman’s dual theory of thinking. I describe this as an “In-between System”. The table below shows how this intermediate decision-making system would be defined.

The In-between System is clearly related to the concept of “unconscious thinking” that Ap Dijksterhuis and some others have investigated. According to his experiments, when making complex decisions, a short period of unconscious thinking leads to a better decision. The human mind is not able to consciously manage a large amount of information in a short time.

However, through unconscious thinking each piece of information is associated and integrated with the rest, facilitating diagnosis and, consequently, leading to a better solution. Unconscious thinking allows decision-makers to dig deeper into the available information and work out new solutions other than the obvious ones that emerge as soon as a problem is presented.

In our example of healthy bakery goods, if the decision maker had let his or her mind run its course for a while, he or she would probably have achieved a better diagnosis of the problem, have found a way around the temporary budget constraints, and taken advantage of the healthy-eating proposition made by the bakery – and all without the need for a time-consuming in-depth analysis of the matter.

The right timing of management decisions

In today’s fast-paced business environment, speed seems to be part of the essence. The pressure to be efficient is high and many leaders feel the need to move fast to remain competitive.

Speed in decision-making can lead to a dynamic organization that is able to adapt to changing market conditions, but it can also lead to hasty and ill-considered decisions. Leaders need to strike a balance between speed and thoughtfulness, and this is a real challenge.

The right approach requires taking into consideration the different kinds of decisions a manager faces. In The Wrong Manager, I propose a chart (below) to help sort out the relevant factors. The chart is based on two key variables.

Context can be certain or uncertain. A certain context would be when the problem can be solved by numerical computation so that the result is known with a high degree of probability. In the case of healthy cakes, if you could know the effects of unhealthy snacks on employee performance, you could compare it to the budget for healthy cakes, and assess if the costs would pay off. By contrast, the outcome of a decision in an uncertain context is unpredictable, which is the case with most management decisions.

Complexity may be minor or major. This depends on the factors to be taken into account, the parties involved, the range of options, the sophistication of the problem conditions and the difficulty in foreseeing cause-effect relationships.

In a certain context, a decision-maker would have to try mathematical/statistical or financial tools to reach an objective evaluation. Applying heuristics to such decisions is clearly a lousy move, and following a thorough decision process would be a foolish waste of time. There should be no discussion here. But what happens in an uncertain context?

According to the chart, a complex decision in an uncertain context requires the tools and skills normally associated with management. Applying ‘management’ to a decision means defining an appropriate objective, establishing a set of reasonable alternatives, gathering the relevant information, and conducting an adequate analysis to reach a well-argued solution. If you were to apply heuristics to a managerial decision, the chances of making the right decision would be greatly diminished.

When an uncertain context and minor complexity come together, we can apply heuristics. This is a field widely explored by decision theories; it is where intuition and mindset play a key role. Heuristics are hugely valuable because they can save managers lots of time and resources. But they can also lead to severe problems as a consequence of many factors, among which I would highlight cognitive biases.

The effect of cognitive biases on decision-making is widely known. They distort our perception of reality and influence our judgements. They can cause decisions to be based more on our subjective beliefs and past experiences than on accurate information, and often lead us to make erroneous assumptions and overlook important facts.

This is where the In-between System and use of unconscious thinking come into play, in place of pure heuristics. The recommendation is often simple: cool off, go on with other activities for a while, and come back to the decision later. If you can (and be honest: you usually can), wait a little longer and sleep on it, because tomorrow’s decision will most likely be better than the one you are about to make today. Pressure and haste are always bad counsellors when it comes to making any choice.

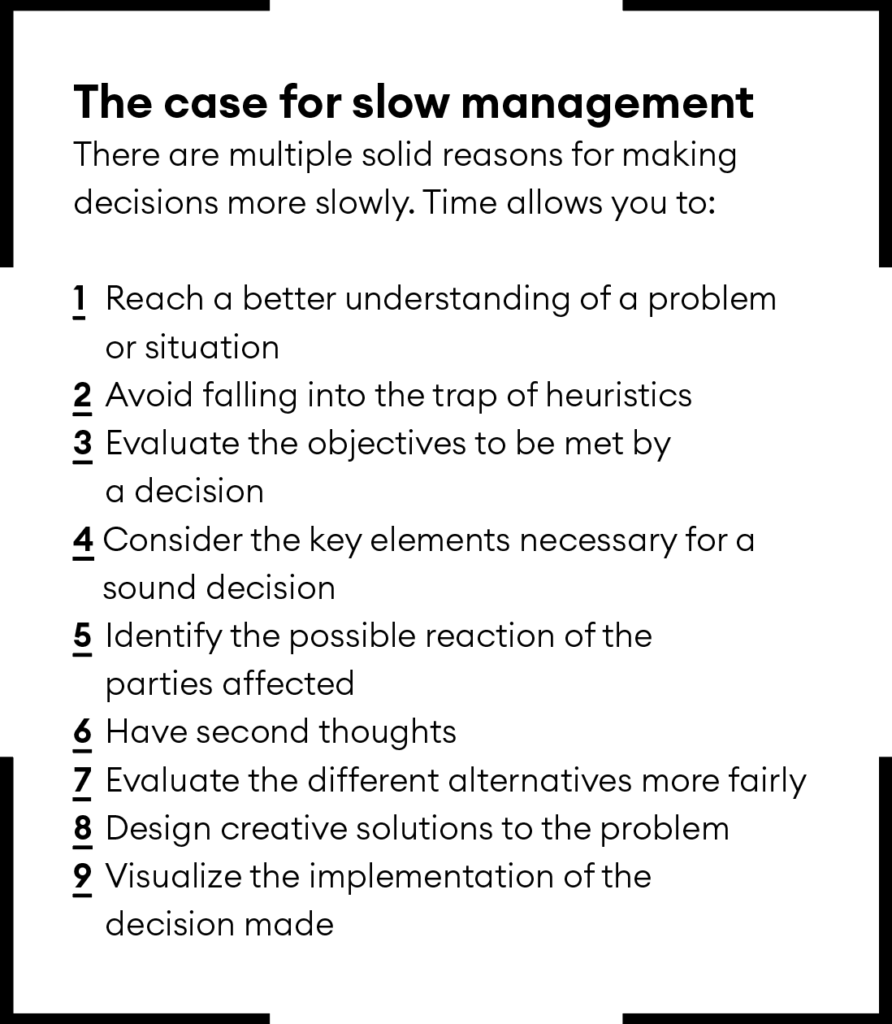

The beauty of slow management

We have seen that rushing is not a good idea when it comes to minor decisions, let alone major ones. It seems obvious, but the belief that success belongs to those who move quickly and make decisions on the fly is common. Leaders should remember that the ‘rush to success’ mentality can lead to the wrong decisions. Taking the time to slow down and carefully consider all available options can yield a significant handful of benefits and, ultimately, greater success.

Missing an opportunity by being slow to decide can happen once in a lifetime; making a mistake by deciding too hastily can happen all the time.

Marce Fernández is author of The Wrong Manager: Management mistakes and how to avoid them (LID Publishing).