Discover the innovation equation, with Anne-Valerie Ohlsson

In the race for competitive advantage and efficiency, companies have subjected their organizations to a series of health and wellness fads. Consider, if you will, the ‘no-fat diet’ (hire consultants, cut the workforce, outsource); the ‘HIIT’ (high-intensity interval training) workout (centralize, decentralize, localize, globalize, repeat); the ‘mindfulness wave’ (à la Google, arguably less successfully). Companies are geared for efficiency, and the drive for this efficiency has long been the foremost concern of the senior management team. And yet, companies today can only thrive if they balance both sides of the ambidextrous organization – innovation and efficiency, exploration and productivity.

As the world grows increasingly connected, globalized, digitized, companies need to adopt an innovation mindset. The need to think like a start-up is critical. But the solution is a great deal more complex than setting up an incubator, or providing employees with innovation time off, or – worse – an innovation bonus. In over 20 years of working with multinationals around the globe, I have learnt this much: only a structured, comprehensive, cohesive approach can help firms seed a sustainable, repeatable innovation and entrepreneurial mindset into their DNA.

The competition for share of mind and wallet is fierce

Challengers fuelled by technology and instant global footprints have blindsided incumbents and reinvented their industries. In most cases, they didn’t even belong to the industry in the first place. How does a Hilton or a Marriott compete with Airbnb when the challenger doesn’t even own hotels? How to compete with a taxi company that owns no taxis and no drivers? And then there is fintech… and insurtech… and the latest… proptech. Legislation lags, regulations falter and the mouse overcomes the mammoth, not only moving his cheese, but eating it.

In faithful incumbent style, the giants of the world are scrambling to catch up. Innovation hubs are flourishing around the globe, with varying degrees of success (read, mostly none). As incubators fail to deliver results, companies have ramped up their quest for the Holy Grail (venture boosters, corporate venture capital, partnerships with universities, research labs, global innovation competitions). And, as with any fad, the results have either failed to materialize or provide lasting results.

Building an innovation DNA

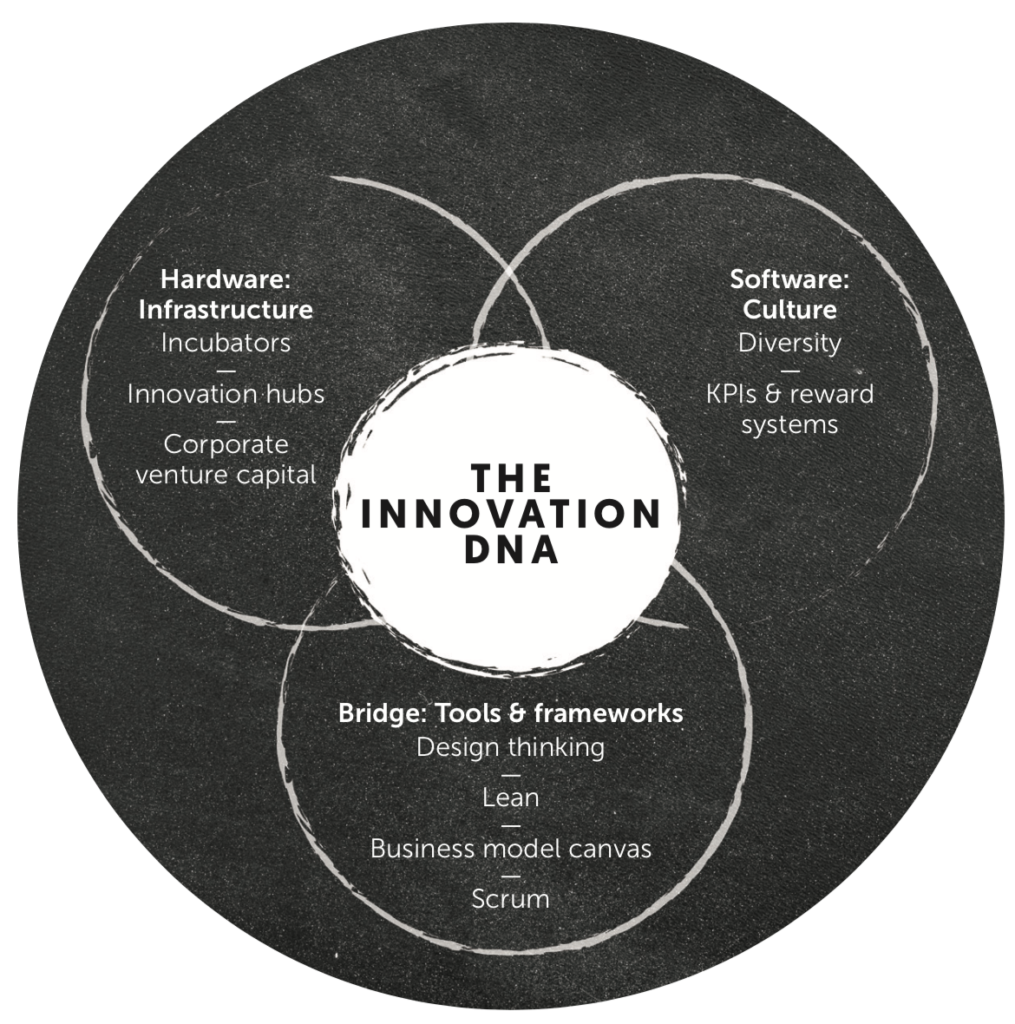

We actually need a three-pronged approach that brings together hardware (an innovation centre), software (a culture that supports innovation), and a series of tools and frameworks that help organizations challenge the existing status quo, assumptions and norms of their industry.

1 The hardware: the easy part

The innovation infrastructure is the easiest part of the equation. Companies launch innovation hubs with the following mandate: “What could wipe out a significant portion of our market share?” They hope that the diversified, cross-functional, global teams assembled will answer questions such as: what happens if people no longer own cars? Which industry are cigarette companies really in? Why is the fintech (technology applied to financial services, e.g. cryptocurrency) industry still based on credit cards?

Some companies have managed to take themselves out of their industry by playing on their strengths and transferring them to different, growing industries. Take the Kodak versus Fujifilm example. Why did Fujifilm not go the Kodak way? Because it was able to reassess its core capabilities. What does it take to make film? Collagen and light. What did Fujifilm go into? Medical technology devices and face cream. Light and collagen. The company’s mission is ‘value from innovation’, and its revenue keeps growing. While Kodak scrambled to contain the technology designed in its own labs by setting up printing booths in supermarkets and malls, Fuji recognized that the era of film and its significant profit margins was coming to an end. By building an innovation team, setting up an innovation centre with significant resources and making the conscious decision to look outside its own industry, Fujifilm was able to reinvent itself, rather than fight a losing battle against the consumer.

The problem? To date, incubators and other forms of venture boosters have yielded little success and most of them have closed down or moved into R&D. Why? Because the culture doesn’t support experimentation, failure, chaos, all of which are intrinsic to exploration, or innovation. Embedding a Google, Netflix or IDEO-like culture is not easy: employees of a large consumer goods multinational recently confessed that while the management had installed a pool table, no-one used it, fearing they would be perceived as lazy or slacking off. Another client confided that only projects in line with current revenue generators were funded and were the only path to promotion, discouraging the development of wild ideas or the search for solutions to wicked problems.

2 The software: a culture of experimentation

Setting up an innovation infrastructure, whatever its shape or form, is a necessary first step: it sends the signal that the company is willing to invest resources. The real challenge is to create a repeatable, sustainable formula – a mindset of innovation across the company, accepting a messy, chaotic process that goes against the drive for efficiency embedded in large companies. The willingness to experiment, the idea that failure is part of a learning process and not the end of a career.

Companies need a culture that supports the explorative, uncertain, wasteful nature of innovation. It is about embracing a form of focused chaos, and it includes rethinking performance indicators, reward systems and promotion criteria. Some questions include:

- Values – What do we stand for in terms of innovation?

- Resources – How do we support our innovation efforts?

- Processes – How do we get innovation done?

- Behaviours – How do we think, approach and act in order to foster innovation?

- Success – How do we measure our innovation output?

Supporting creativity and experimentation through organizational design and human capital strategies is the most difficult aspect of the innovation equation. Painting a wall blue is easy. Accepting that employees work on their own projects, spending corporate resources while trying to work out if walls should exist in the future, is more challenging. A number of companies, such as 3M, or Virgin, encourage ‘dabble time’. Sir Richard Branson believes that CEO should stand for chief enabling officer, growing a generation of ‘intrapreneurs’ that will come up with the next big ideas.

3 Bridging hardware and software

Branson has a point – companies need to acquire the skills of a start-up, and employees should think like entrepreneurs in pursuit of innovation. There are many frameworks which aim at creating ambidextrous, agile organizations that harness the resources of a large multinational, with the nimble market approach of a start-up.

To be truly innovative, a focus on customer pain-points through design-thinking requires companies to think beyond their existing frame of reference, reaching out to non-users, extreme users. This approach requires an understanding of how trends are converging in the real world. It is not about focus groups or close-ended survey questions. This is about observation, about gaining a different perspective. The question is always – does my product or service address the customer pain point? What is the opportunity? Where is the threat? What am I doing for my customer?

Another technique is pivoting, a word out of Silicon Valley to describe a key business attribute possessed by some of the world’s most innovative companies. The tech entrepreneurs who started Instagram, for example, which sold to Facebook for $1 billion, began with an idea for an online check-in app and, when that failed, they worked through ideas until they came to a photo-sharing app. Starting something, determining it’s not working, and then leveraging aspects of that technology is powerful. And let’s not forget either lean methodology or Scrum, a framework for Agile software development (not an acronym, first used by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka in their ground-breaking 1986 paper The New New Product Development Game).

While brainstorming, ideation or ethnographic market research help companies initiate the innovation journey. Nothing happens without execution. Exploring potential new markets through redefining the company’s value proposition and developing a business model canvas (a strategic management and lean start-up template for developing new or documenting existing business models) helps companies think about the implications of a new product or service. It allows companies to answer questions such as: is the value proposition aligned to the customer segment? Think back to Nespresso and the fact that for its first 15 years, it missed the idea that there was a consumer market for their product beyond the office segment. Would Nike have made yoga shoes, had an employee not noticed that women were looking for a total look to walk to their studios in?

The plethora of start-up tools accessible to organizations helps them bridge the hard and soft aspects of the innovation equation by bringing together a space and a culture, creating an ecosystem in which innovation can thrive.

Sustainable innovation

A sustainable innovation strategy is about bringing together all three aspects of the innovation equation as an ecosystem in which companies learn to live with not knowing all the outcomes, being flexible, adaptive and agile, embracing multiple perspectives, and supporting boundaryless environments.

WL Gore is an example, built on the values and entrepreneurial spirit of Bob Gore, who, in 1957, bought the Teflon patent from his employer DuPont. By 2011, the company had over 2,000 patents, including Gore-Tex. The company pursues innovation through a combination of design (flat, little bureaucracy, a great deal of autonomy, a tolerance for failure) and a willingness to experiment and give innovation a chance, as exemplified by the Teflon-coated guitar strings which they launched on the market after three years of experimentation. The strings cost four times that of the average string and the company gave artists over 20,000 free samples to convince them that this was a superior product. Today, they are the leading product on the market. Leaders at Gore can only lead if teams choose to follow them, and they need to explain themselves and their actions. Projects are selected if they respond to three questions:

- Is it real?

- Is it worth it?

- Can we win?

There is no formal organizational chart and every time a location grows to 250 employees, a new office is set up, so as to keep each location small. While the firm is still privately held, employees co-own 25% of the company, sharing in its success. The model is not easy to emulate, as it is based on a number of assumptions: trust that people will, when given the choice, do the right thing; comfort to operate without assumed authority or control.

Supporting and developing an innovation DNA in organizations cannot be driven by fad. Solutions are complex and diverse, like the world we live in. The talk around disruptive innovation has driven fear into the heart of potential innovators, yet most innovations are incremental. Not every company will invent the gramophone or the Post-it Note, but companies such as 3M or Gore have turned innovation into a systematic, replicable approach. You could too.