Humans trust one another. But can they trust organizations? With the right strategies, they will, write Professor Dan Ariely and Logan Ury

Human beings have an innate ability to trust one another. We vary in how trusting we are, and we might choose people we trust carefully. But, generally, we trust. Have you ever been in a café and asked someone to look after your things while you make a trip to the lavatory? Or given a neighbour a key to check on your home while you are away? That’s one of the reasons business propositions like eBay, Airbnb and Uber work. And it’s even truer for Generations Y and Z, which celebrate living in a sharing economy.

Want more scientific proof? In the trust game, you are paired with a stranger and given $10. You can either keep the $10 or send some of it to your partner, who will receive triple the amount you send them and can then choose to send as much as they want back to you. Standard economic theories assume that self-interest would predominate: since you have no reason to believe that your partner will give you anything back, you will keep the money for yourself. However, across many studies, researchers found that, in the vast majority of games, the initial players sent money to their partners. Moreover, their partners rewarded them for this trust: on average, the second player returned more money than originally received from the first player.

This demonstrates that individuals tend to trust others, even when that trust compromises our own material self-interest. Despite seeming irrational, this kind of behaviour makes sense. In a world in which we are not completely self-sufficient, we need reciprocity to live and work together. We might not articulate that reciprocity, but we’re motivated to trust one another because living in a trusting community is advantageous to our survival – and that’s the basis for trust.

Trust generators

Real trust is much harder to achieve when one of the players is a large business. As corporations are, for the most part, faceless, it is not at all obvious to individuals in whom they are placing their trust. Thus, businesses need to find methods beyond meet-and-greet as mechanisms to build trust. So what do they have at their disposal and how can they use these as trust generators?

There are many aspects and building blocks for trust, but here are five key mechanisms that allow human beings to trust one another: long-term relationships, transparency, intentionality, revenge and aligned incentives.

1. The long game: established relationships

Imagine two new people join your team at work. One is on rotation for a week and the other will be your partner for the next three years. Who do you feel more invested in? Who are you more likely to trust? Professors of economics and social science James Andreoni and John Miller (1993) tested the effect the length of a relationship has on our tendency to trust others. In a typical prisoner’s dilemma game (see infographic, page 20), players can either look out for themselves or cooperate with their partners. If both parties cooperate, both benefit. If not, the player who cooperated is hurt. Andreoni and Miller tested situations in which people were paired with the same partners for multiple rounds, or switched to a new partner each round. They found that with consistent partners, and thus a chance to build a good reputation over repeated interactions, people were much more trusting: they cooperated 63% of the time, compared to the 35% cooperation rates when partners switched after each round.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this research shows that we are much more trusting when we think our interactions will extend for a longer period of time. In each interaction, each partner has the opportunity to prove, over and over again, through productive interactions, that they can be trusted to cooperate, and in the process each builds a good reputation for trustworthiness.

Applying the Long Game to corporations

The internet has made it much easier for customers to shop around, rather than staying loyal to one supplier. With this relatively frictionless switching, many companies have focused on flashy short-term deals that appeal to our short-term focus. But with the avalanche of such deals, customers have also become sceptical about the corporations that offer such shiny

conditions to attract new customers while being less favourable to their existing – and potentially loyal – customers. Here are three general ideas for corporations to build longer-term

relationships and thus become more trusted suppliers:

Three ways to build relationships

- Recognize loyal customers via badging – “customer for ten years” – to show you appreciate how long they have been with you

- Reward longstanding customers with loyalty benefits just as you might use promotions to attract new customers

- Launch programmes and products that help loyal customers but have no immediate or obvious benefit to yourself (and may even have a cost to you)

2. The glass door: transparency

Research tells us that human beings are poor at spotting liars (the exception is that liars are good at spotting other liars). For example, see psychologist Paul Ekman’s research,Why Don’t We Catch Liars?(Social Research, 63:3, Autumn 1996). Even polygraphs miss lies, because they detect emotional reactions such as fear – and often we are not emotional about lying. Some studies suggest lies can be detected by means other than a polygraph – by tracking speech hesitations or changes in vocal pitch, for example, or by identifying nervous adaptive habits like scratching, blinking or fidgeting. But most psychologists agree that lie detection is destined to be imperfect. So transparency is crucial because it assures people that the other party is unlikely to misbehave because their behaviours are being monitored. Transparency also helps people understand what’s actually happening. We’re more comfortable in situations where we can see what’s going on behind the scenes.

Applying the Glass Door to corporations

We’ve all had negative experiences with companies. All you need to do is spend a few moments on the @comcast Twitter feed to understand how betrayed people can feel by corporations, particularly cable, internet, or phone providers. Therefore, when we come to evaluate a new service or organization, there’s a good chance that we’ll take our own expectations with us, many of them clouded by salient negative experiences, and use that as a starting point in the relationship. We wear grey-tinted glasses to view our new experience. If a customer is already distrusting when entering a relationship with a company, how can that company grow user trust? One method is through transparency.

After a scandal that includes a breach of trust, governments often increase transparency measures in order to help rebuild trust. For example, after the 2008 financial crisis, the US Securities and Exchange Commission responded with the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.The goal of this legislation was to “support an entirely new regulatory regime designed to bring greater transparency and access” to the financial markets and to financial institutions. Of course, transparency is not the same as deep trust, and it is about being closely monitored rather than being trusted, but it is an important intermediate step as we try to create real trust.

We can see the power of transparency in the corporate world as well. Berkshire Hathaway, for example, builds trust through transparency in its incredibly detailed annual shareholders’ report. Its letter to shareholders always begins by outlining any mistakes from the previous year. Shareholders are then likely to be more trusting of the rest of the information contained in the document.

Three ways to improve transparency

- Encourage all feedback – positive and negative – from your customers and make it simple to report and find online

- Outline in your corporate reports and other public outlets mistakes the company has made, and explain what steps you are taking to rectify them

- Explain the thinking behind any controversial aspects of company policy in easy-to-grasp ways

3. The why factor: intentionality

Author Simon Sinek’s popular Ted Talks demonstrate the impact of explaining why we are doing something, before moving on to elaborate on exactly what it is we are doing. And from another area of study entirely, author Fons Trompenaars’ research on cross-cultural differences also shows the importance of intentionality. Here is his apparently simple dilemma: you are in a car, your friend is driving and speeding, and accidentally knocks down a pedestrian. And now, comes the question: “When you are questioned about the incident do you tell the truth or do you lie?”

This scenario elicited a wide range of responses. No one was comfortable in a situation in which someone might need to lie for them, but the value of friendship sometimes overrode the desire to see justice served for the accident. Across the world, those struggling with the dilemma wanted to know more about what actually transpired and what their friend might have been thinking. So they asked questions like “did the pedestrian die?” and “did the friend expect them to lie?” They essentially cared about the underlying reasons behind the behaviour. More generally, people evaluate our intentionality – the perceived reasoning behind our actions.

They’ll judge us much more harshly if we answer a moral dilemma very quickly, or if we seem to derive some pleasure from another person’s suffering. We are judged less harshly if we seem to ponder our choices for a long time and we suffer as we struggle with the dilemma, and empathize with those who suffer because of our decisions.

Our reliance on intentionality is partly about our quest for finding common ground, including mutual values. We use intentionality to decide whether someone is similar to us, because we feel more comfortable with people like ourselves. Intentionality provides a clue to working out whom we can and cannot trust. Understanding people’s thought processes helps us evaluate their broader sense of morality and allows us to protect ourselves against people who may intend to harm us.

Applying the Why Factor to corporations

The New York Times puts a lot of effort into demonstrating its intentionality. The newspaper has a public editor – someone outside of the normal editing and reporting structure – who focuses solely on interacting with the public. After its website redesign earlier this year, the paper’s public editor wrote an article detailing the major complaints she’d heard and explaining why certain decisions had been made. This insight into the paper’s reasoning for its decisions – its intentionality – helps to build trust (and at the same time is also a nice example of transparency).

Three ways to demonstrate positive intentionality

- Explain to the public why you took unpopular decisions: for example, why you decided to retire certain product lines

- Use campaigns to show and tell how your actions demonstrate that you share your customers’ values

- If you are forced, by outside agents – such as the government – to do something your customers don’t like, explain this process clearly through clear messaging: for example, “the State of Rajasthan made us do this”

4. The counterpunch: revenge

Perhaps counterintuitively, revenge plays a major role in building trust. People consider the ability to exact revenge for potential wrongdoings a form of informal insurance. When revenge exists, everyone knows that if a transgression takes place, the outcome for that person will be devastating. The possibility for punishment or revenge also helps us avoid asymmetrical relationships – in which one side is more open and vulnerable than the other. Reducing the sense of an asymmetrical relationship is a key benefit of revenge.

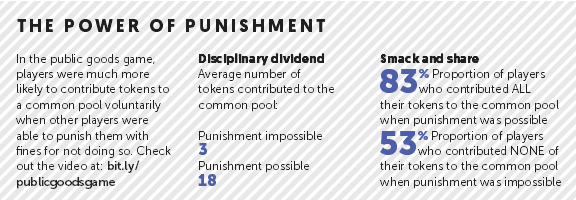

Professors Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter tested the importance of revenge in building trust in the public goods game. In this exercise, people can take a risk with their own money and trust other people to reciprocate. If the other players decline to reciprocate, the original investor loses their initial investment. In some conditions, if the trust was not reciprocated, the betrayed players could sacrifice more of their own tokens to punish the betraying players. This did not provide the betrayed player with any tangible benefit, in fact it cost them tokens – which have a monetary value. But it provided a sense of revenge because the betraying player would lose much more than the cost for the betrayed player.

Fehr and Gächter found the ability to gain revenge had a significant improvement on the outcome of the game. Where punishment was possible, players contributed two-to-four times more than when it wasn’t. In the final round of the game, the average contribution was more than 18 tokens in the punishment condition, and approximately three tokens under the no punishment condition. What these results suggest is that one key benefit of allowing someone to exact revenge or punish is that it reduces the sense that one party has a lot more power and control than the other party, or that they have an asymmetrical, rather than a balanced, relationship. And this ability to control the outcomes of the other players involved helps build trust.

Applying the Counterpunch to corporations

Knowing we can return, at no cost to us, that ‘miracle’ anti-balding medication, or review a restaurant, makes us feel more powerful and more comfortable and willing to take a risk.

Three ways to allow revenge

- Devise online tools through which your customers can comment upon, even criticize, products and deliveries. Make sure they know about these tools in advance, so they recognize the balance of power in the relationship

- Promise customers something for free if you fail to meet your obligations on a product or service – doing it after the fact is nice, but the customer being aware of it before the event is what changes the perception of the power balance

- Allow your customers time and space to vent. Be prepared to find a manager quickly and easily when angry customers ask to speak to one

5. The common goal: aligned incentives

What happens when a waiter warns against a certain dish –“the chicken is a little dry tonight” – and then goes on to suggest lower-priced options? Suddenly the restaurant patrons feel their incentives are aligned with the waiter’s motives – and that the waiter has their best interests at heart. A demonstration that we are willing to sacrifice some income for the benefit of the other party can be an incredibly powerful act; it redefines the relationship from that of buyer and seller to buyer and adviser. The patrons now trust the waiter’s intentions implicitly. Somewhat ironically, this gives the waiter an opportunity to upsell wine and dessert, and probably earn higher tips.

The moment there is a signal that the incentives of the waiter and the customers are aligned, trust increases. Once again, this type of increased trust is easily achieved in a person-to-person setup. We can look the waiter in the eye, listen to his advice, make a judgment about how truthful and helpful he is being and decide to what extent we should trust him.

But what about corporations? Capitalism is in crisis. Much of the problem is down to the public having seen enough examples of bad behaviour to taint its view of corporations as a whole. Rather than entering the relationship based on real trust, as we would with another human being, we enter the relationship expecting to be disappointed, let down, or, even worse, exploited. Starting any transaction or relationship this way is not a recipe for success.

Applying the Common Goal to corporations

Companies demonstrate aligned incentives by recommending things that are clearly not in their best interest. For example, Progressive Insurance builds user trust through its recommendation engine. It shows potential customers a selection of insurance quotes from other providers in addition to its own. Because Progressive is often, but not always, the least expensive, users feel they have aligned incentives, and the company appears trustworthy.

Three ways to align incentives

- Allow your salespeople to recommend suitable products to customers that are clearly of high utility for the customer, but lower price or lower margin for the company

- Offer your customers simple ways to compare your product with those of your competitors

- Give fair assessments of your competitors’ products, even if that means being more positive than you wish to be

The future of trust

Successful companies are already working with individual customers in a way that simulates how individuals create real trust with one another. The ability to create and nourish trust is open to all companies, and many should do more to minimize their image as a faceless giant working against helpless individual customers.