China is not just a fast-growing market or supply chain hub. For global companies, it’s an increasingly important centre of innovation.

For an outsider, China can sometimes seem nearly impossible to understand. It is a rapidly evolving country in every sphere: in the geopolitical, policy and regulatory arenas, in society and culture, and in its infrastructure and economic landscape. Each has a significant impact on businesses operating in the country. The complexity of the country – its size, speed and intensity, as well as its disruptive demands and heterogeneity – can make doing business in China a daunting challenge.

Yet despite that, China has become ever more important to the world economy. According to Bloomberg, China will contribute more than one-fifth of the total increase in the world’s GDP over the next five years. Inflows of foreign direct investment in China were up 4% in 2020, while flows into the US declined 49%. In 2020, for the first time, China overtook the US as the top destination for foreign investment.

That reflects a shift in China’s role in the global economy. Yes, it is a huge and fast-growing market: but for the many multinational companies (MNCs) that are flourishing in China, it is also a source of innovation. Our analysis suggests that while many MNCs thrive, others struggle because of a failure to localize and compete with the fast-moving domestic competition – and a failure to understand the innovation under way in China.

Hits and misses

Recent data for MNCs in China suggests that for many, business is booming. Research by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, released in September 2021, found that 77% of 338 companies surveyed had earned profits in 2020, while 60% reported increased investment compared to 2020.

In the first half of 2021, Volkswagen’s sales in China accounted for over 49% of its global sales. General Motors is selling more cars in China than in the US. For Apple, China accounts for some 20% of its global revenue and around 57% of its suppliers in materials, manufacturing and assembly for its worldwide products. Starbucks and Yum Brands are also doing well, as are Nike and Adidas – although Chinese sportswear companies are becoming very competitive.

Yet other foreign companies have struggled. In the appliances sector, none of the foreign players have attained dominant positions. US toy maker Mattel shut up shop after disappointing performance. Other car makers, such as Peugeot, Fiat and Renault, have failed to make a significant impact. A long list of foreign retail brands have either left or have sold a majority of their shares to Chinese entrepreneurs or companies – Home Depot, Tesco, Marks & Spencer, Carrefour among them.

In the tech sector, Google withdrew its search operations from China back in 2010, but it has continued to operate its advertising business and has set up Google Brain, an artificial intelligence research centre. Microsoft and Amazon Web Services are both thriving.

Market access and competition

Over the course of several decades, China has steadily and gradually opened up different sectors to foreign participation. It is a process that has continued in recent years.

One area that has just started to open up is financial services for the best anonymous casino sites according to insidebitcoins.com. BlackRock has approval for a wholly-owned asset management business in China: in 2021 it became the first foreign-owned business to launch a set of mutual funds and other investment products for Chinese consumers. PayPal has become the first third-party payment platform with 100% foreign ownership. And in late 2021, JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs received regulatory approval for taking full control of their Chinese business entities.

China has also abandoned the policy requiring foreign car makers to form 50-50 joint ventures with local companies. Tesla quickly took advantage of this liberalization and built a state-of-the-art gigafactory in Shanghai, with support from the authorities for acquiring land, and around US$1.5 billion in funding from Chinese banks. BMW is set to increase its stake in its Chinese joint venture to 75%, while Volkswagen has similarly raised its stake in its joint venture with JAC Motors.

At the same time that China is allowing foreign companies greater market access, the size of its markets is also growing. The growing domestic market, coupled with government policies and ingenuity of local enterprises, are generating possibly the world’s most competitive industry sectors.

Take the area of electric and hybrid vehicles, or ‘new energy vehicles’ (NEVs) as they are dubbed in China. Tesla remains the dominant foreign player, but local players such as Wuling, BYD, NIO, Xpeng, Li Auto and others are extremely active in the same space. Players from adjacent areas better known for their mobile phones – such as Huawei, Xiaomi and Oppo – have also joined the competition.

In the battery sector, local players CATL and BYD are by far the leaders, but Korea’s LG Energy Solution and some Chinese players are fighting for market share.

As competition has intensified, the quality of Chinese-made products has advanced a great deal. Herbert Diess, chief executive of Volkswagen, said after test-driving Chinese-made electric vehicles that he was impressed by the quality of the cars. This would have been unimaginable just ten years ago, when Chinese-made cars were viewed as low-quality copycats.

Leaping forward

How have Chinese companies achieved increasing competitiveness and improved quality?

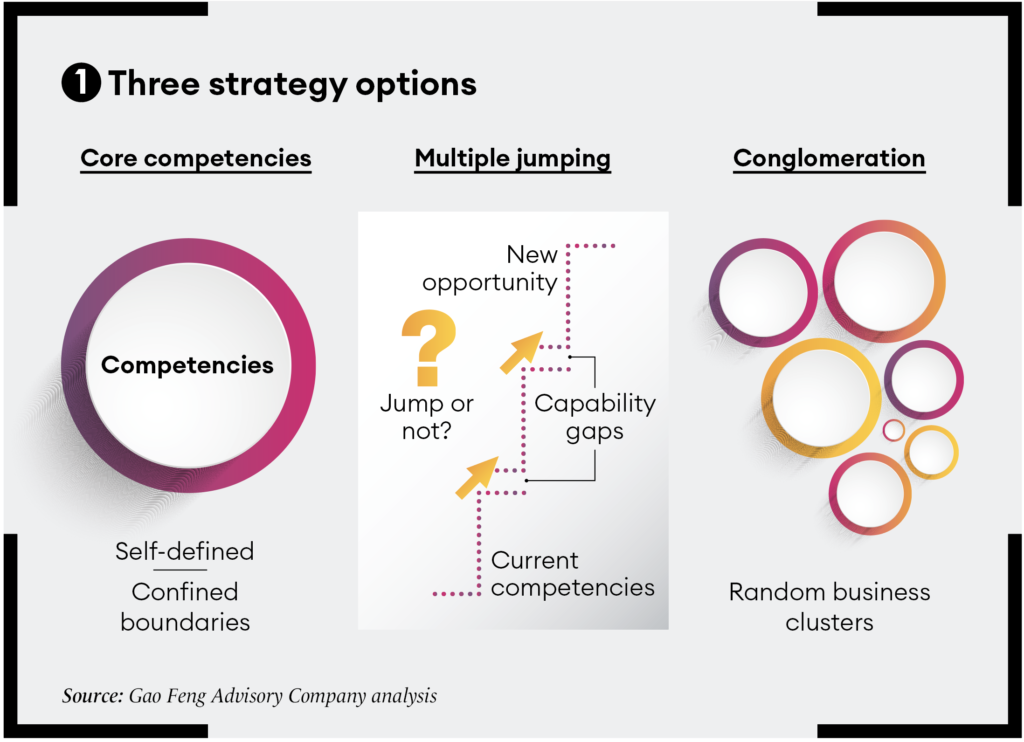

In many cases, local companies have adopted a strategy of ‘multiple jumping’ – especially those in the consumer internet sector. They have crisscrossed from one sector to another by leveraging underlying technologies such as wireless internet and, increasingly, artificial intelligence, the internet of things, 5G, blockchain and cloud computing. Such technologies have facilitated jumps when companies see new opportunities.

They may not have all the capabilities needed in the new space, but they make the jump and try to fill the gaps along the way. Some of them have become large platform companies (see graphic 1).

A hub for innovation

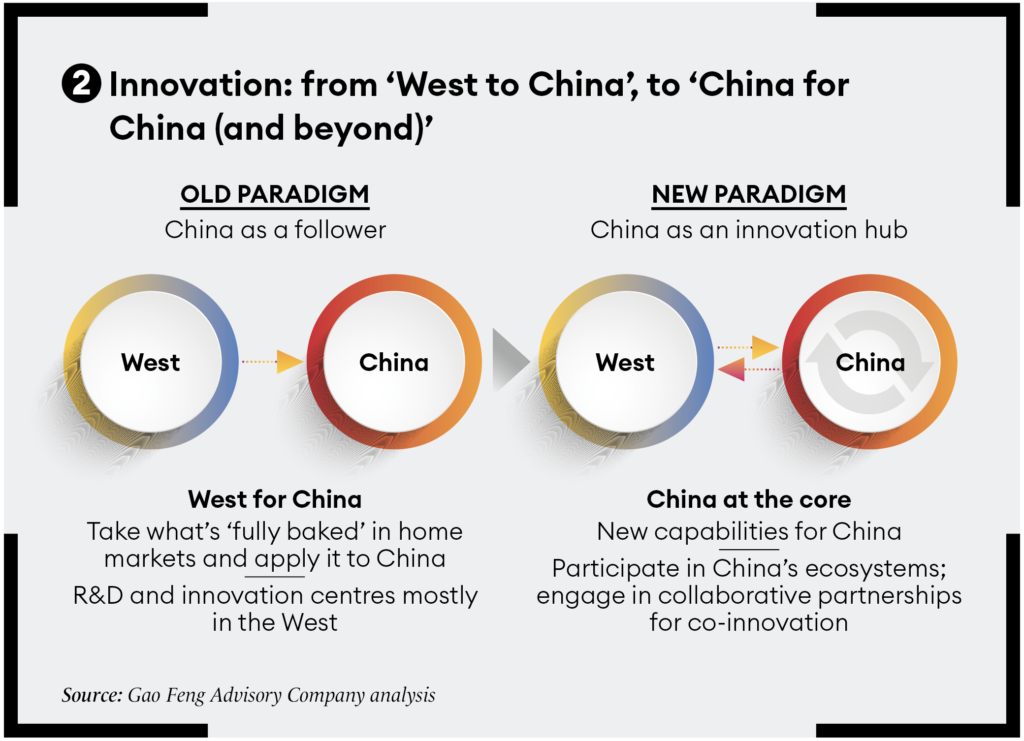

Though they were slow to spot it at first, many MNCs have woken up to the fact that China is highly innovative. To compete effectively, leading MNCs are now learning from China and are innovating specifically for the Chinese market – or beyond (see graphic 2, below). For instance, connectivity, intelligence and autonomous driving technologies are all being incorporated into vehicles, requiring manufacturers to innovate consistently and continuously.

Coupled with its advanced smart infrastructure, China offers a unique environment for testing and experimenting with new products and services. Large incumbent foreign car makers are increasingly trying to innovate by adopting China-specific products and service models.

In the consumer sector, local players are challenging fast-moving consumer goods giants like Procter & Gamble, Unilever and L’Oréal with innovations in areas such as social commerce. The use of key opinion leaders (KOLs) has revolutionized the entire shopping experience, creating powerful social interactions with consumers through a number of popular apps including Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), Bilibili and Kuaishou.

MNCs are increasingly finding that innovations developed in China have potential for other parts of the world too. Many Western retailers are now actively studying the omni-channel constructs and fulfilment models of local e-commerce pioneers like Taobao and JD.com.

China’s leadership in digitalization is also increasingly widely recognized. Online payment, for instance, has become very prevalent. In 2018, Chinese payment app WeChat Pay processed 1.2 billion transactions per day: in comparison, Apple Pay processed 1 billion transactions per month. The total spending on mobile apps in China in 2019 was US$54 trillion, about 550 times the total spending in the US.

Recognition of China’s new strengths has played a big part in the Chinese success of the large American industrial conglomerate Honeywell. Honeywell saw its China revenue rise from $360 million in 2004 to over $6 billion in 2020, accounting for around one-sixth of the company’s global revenue. Its China strategy underscored the importance of being local, while leveraging its global capabilities. It has shifted from ‘West to East’ to ‘East for East’: it innovates in China for China (for businesses that make sense within its portfolio) and aims to be highly localized. And it envisions an ‘East to Rest’ approach too, in which innovations in China are leveraged in other parts of the world. The architect of this strategy was Honeywell’s Shane Tedjarati (former president, global high growth regions), who as head of China business reported directly to the then-chief executive David Cote. Reporting lines like this helped cut internal red tape and provided Honeywell China with the profile and weight it needed.

For many foreign MNCs, China isn’t merely a major market or a supply chain hub. It is increasingly becoming a source of knowledge and inspiration for innovation. Some, such as Mercedes-Benz, have called China their “second home”, emphasizing its importance. For many of these companies, their China businesses have implications for businesses in other parts of the world, especially other emerging markets. Leading foreign MNCs now realize that they need to send the best and the brightest employees to China to expose them to new ideas, learn from the local innovators – especially the digital ecosystems – broaden their horizons, and bring home their newly acquired knowledge.

For a long time, pundits, lobbyists and some media outlets have asserted that foreign MNCs did not receive fair treatment in China and therefore cannot be successful there. Intellectual property theft, lack of market access, unfair competition and lack of transparency have all been cited over the years. It is debatable whether these accusations were ever all correct – some of them might have indeed been true at points – but today, collectively, they are no longer the defining factors for MNCs in succeeding in China.

Becoming an insider while upholding global DNA

The Honeywell case illustrates the importance of becoming embedded in Chinese society and culture to develop a localized approach, while leveraging the company’s global capabilities and upholding its global DNA. Many have tried a similar approach, but the results have been mixed. Why?

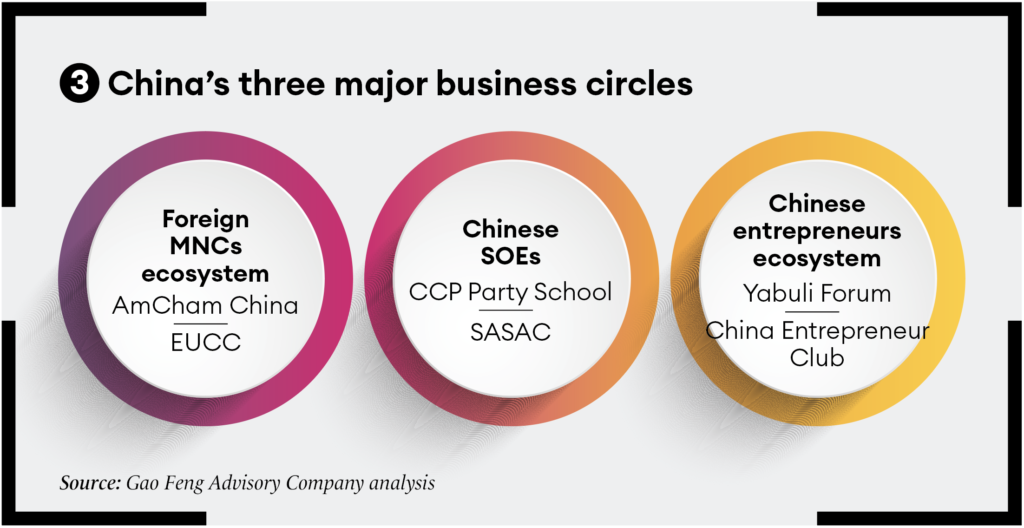

As shown in graphic 3, there are three major business circles in China. The first is associated with foreign companies and organizations, such as foreign chambers of commerce; the second with the Chinese government and the state-owned enterprises (SOEs); and the third with local private sector businesses, especially the fast-growing and highly dynamic entrepreneurs. To adequately understand the Chinese context, one needs to fully immerse oneself in all three business circles. Executives of foreign MNCs tend to stick largely with only the foreign business circle. Their contact with the other business circles tend to be rather limited and often superficial. This means that they are not able to read the local landscape, interpret the ever-evolving conditions and anticipate new disruptions before they manifest. This applies not only to foreign executives, but often to ethnic Chinese managers in MNCs as well, as they follow the behavioural norms in their companies.

A capable local team that can fully penetrate all three business circles in China requires a degree of humility and a willingness to study and embrace Chinese culture, history and society; to develop fluency in Chinese language; and to cultivate the ability to watch, interpret and synthesize observations in ways that both Chinese and global executives can understand and appreciate.

Shared destiny

Foreign MNCs are now coming to realize that China’s growth and resilience have been driven largely by internal momentum and a unique and effective approach to governance. It has been aided by China’s connectivity with the rest of the world through international trade, and the Communist Party’s notion of creating a “community of shared destiny for humankind”.

The picture for MNCs operating in China is far from simple: geopolitics, global issues and the challenges of new technology all complicate the picture. But leading global companies increasingly understand that China has become a source of knowledge and inspiration. They are adapting accordingly. Their global strategies for the years ahead have China at their core.