Look East for the new way to win, write Mark Greeven and Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez

Most Western companies have a functional/hierarchical structure. This was ideal for running a business efficiently in a stable world. Departments are divided along a value chain influenced by US academic Michael Porter’s value chain model. Traditional companies are generally run by a chief executive, a chief financial officer, and often a chief operating officer and a chief information officer, followed by the heads of business units and functional departments. Each has their own budget, resources, objectives and priorities. Hierarchical organizations consolidate information and control only a few people at the top of the companies. The most important and strategic decisions are taken by the leading group, often slow and far from the market reality.

Until recently, departmental success was measured using key performance indicators tailored to each unit or function. The finance department’s success was measured by whether it was closing the books and producing the financial statements on time; the HR department by whether it had managed to keep good people on board (low turnover) or had finished employee appraisals on time.

This approach creates significant internal competition, often leading to the well-known ‘silo mentality’. Some heads of department build their own little kingdoms, and cooperation with other parts of the business becomes difficult, sometimes impossible. In many cases, the key performance indicators of one department are at odds with those of another.

At the same time, the largest and most critical projects — the strategic ones — are almost always transversal. A strategic project, such as digital transformation or expansion into another country, requires resources and input from several business units and departments. Facility experts find the location, lawyers handle the legal documents, HR experts recruit the people, and salespeople develop a commercial plan, and so forth. Without the contribution of all these departments, the project will not succeed.

Cross-departmental — or company-wide — projects in a traditional functional organization always face the same difficulties, some of which are linked to the following questions:

- Which department is going to lead the project?

- Who is going to be the project manager?

- Who is the sponsor of the project?

- Who is rewarded if the project is successful?

- Who is the owner of the resources assigned to the project?

- Who is going to pay for the project?

Adding to this complexity is the silo mentality, with managers often wondering why they should commit resources and a budget to a project that, although important, would not give them any credit if successful. Rather, a management colleague, often an internal competitor, would benefit.

Within the traditional functional organizational structure, quick project execution is not possible. Managing just one project in such a complex structure is a challenge, so imagine the difficulty of selecting and executing hundreds of projects of varying sizes.

The Chinese way

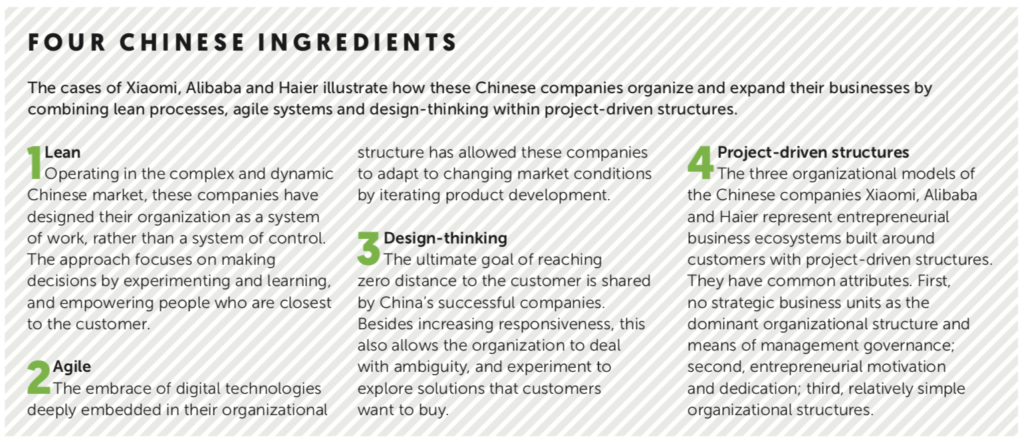

Faced with a silo mentality, a lack of agility, attachment to the status quo, innovation paralysis, and all the downsides of traditional organizations, Chinese companies have frequently managed to successfully reformulate their organizations. Consider three successful Chinese organizational models:

Xiaomi, an electronics company, started life in 2010 and has grown rapidly. It outstripped Apple’s smartphone sales in China within four years. It then introduced new products to the market at breakneck speed, disrupting, or at least surprising, market incumbents every time. By 2018, Xiaomi had successfully introduced over 40 products, ranging from smart rice cookers and air purifiers, to robot vacuum cleaners and smart running shoes.

However, the truly innovative aspect of Xiaomi is how its organizational model is driven by projects. Its 40-plus products in the market are not organized in strategic business units and have not become part of the organizational hierarchy.

The company has a relatively flat organizational structure: the seven cofounders are only one line of management away from the engineers and sales. The latter make up the largest part of their employee base. Moreover, the cofounders are required to be involved with projects and new product development directly. They participate in user interaction, such as on Xiaomi’s own platform, and keep up-to-date with products. Each Xiaomi employee, including the founder, has contractual responsibility to directly deal with a certain quota of customer requests. A sophisticated digital problem distribution system allocates questions to any suitable employee. Each new product development is treated as a project that can be achieved by mobilizing resources inside and outside Xiaomi. Two features stand out:

- Iterated product development in customer-driven projects;

- Leveraging an ecosystem of external resources to speed up project execution.

Xiaomi uses a new product development approach that focuses on getting prototypes to market as soon as possible, i.e. with good-enough products, and actively involves users in fine-tuning and updating the technology and design. The result is a product that is largely co-developed by the community, i.e. closer to the market need, and with a more efficient R&D process. The key competence of Xiaomi is a project-driven structure where the business model, marketing and promotion and design, centre on customer interaction, rather than manufacturing. The result is that it can deliver good-quality products that customers want, without the investments in production and R&D that a traditional organizational model would require.

Second, customer-driven projects gain speed in Xiaomi by leveraging external resources. Following its three original designs – the smartphone, TV set top box and router – all other Xiaomi products were developed as projects in collaboration with other companies or entrepreneurs.

Alibaba Group is the world’s largest and most valuable retailer. Its success can be largely attributed to its new organizational form, a business ecosystem, which has fostered the rapid growth and transformation of its businesses since the company began life in 1999.

Its business ecosystems consist of hundreds of companies, ventures and projects across at least 20 different sectors. But the majority of these are independently run operations, neither part of strategic business units, nor subject to reporting structures. In fact, many of the players in Alibaba’s business ecosystem are still fairly small in size.

Alibaba is widely characterized by dynamic systems of companies, ventures and projects enabled by digital technology. Instead of directing the development of new products and implementation of a project top-down, Alibaba functions as the gravity provider and network orchestrator. For instance, Alibaba’s core comprises four ecommerce platforms (Alibaba.com, 1688.com, Taobao.com, Tmall.com) that are home to 700 million users. Moreover, the interdependence between the companies, ventures and projects is not only financial- and equity-based, although it is a prerequisite to be part of the business ecosystem. The interdependence is found in growth strategies, investment approaches and resource sharing. Entrepreneurial projects in this ecosystem are allowed to fail without severe consequences for the sustainability of the whole ecosystem, or the careers of top management. Employees in Alibaba’s ecosystem are selected and managed on alignment of values rather than rules.

The consequence of such a value-driven approach is encouragement of taking risks, a strong organizational culture and competition. There is no HR guidebook, only a set of strong principles that guide the employees to operate in a highly dynamic environment. They can initiate any project they like without regard to their current company or department. In fact, the ecosystem of Alibaba provides a safe marketplace of resources in which project initiators can execute without the limits of corporate hierarchical boundaries and complex vertical reporting structures.

Alibaba has made considerable efforts in keeping its business ecosystem entrepreneurial. It has been, by far, the most active generator of new chief executives in China. By the beginning of 2016, over 450 individuals had emerged from Alibaba to start their ventures. In total, over 250 ventures have been established by former Alibaba employees. Many of these new projects are started within the ecosystem of Alibaba, leveraging its rich resources and opportunities. New project initiatives and implementation stay within the ecosystem and do not suffer from bureaucracy, department silos or managerial limitations.

Haier Group is the world’s leading white goods brand. It reached revenue of over 200 billion RMB in 2016 and acquired General Electric’s appliance division for $5.4 billion, a feat unimaginable considering its humble beginnings three decades ago. It has many examples of products that satisfy special needs in China. For instance, washing machines with quick, 15-minute washing cycles. Many of the product ideas come from the front-end of the company, such as repairmen and salespeople. Haier’s Crystal washing machines series is the outcome of a succession of user observations.

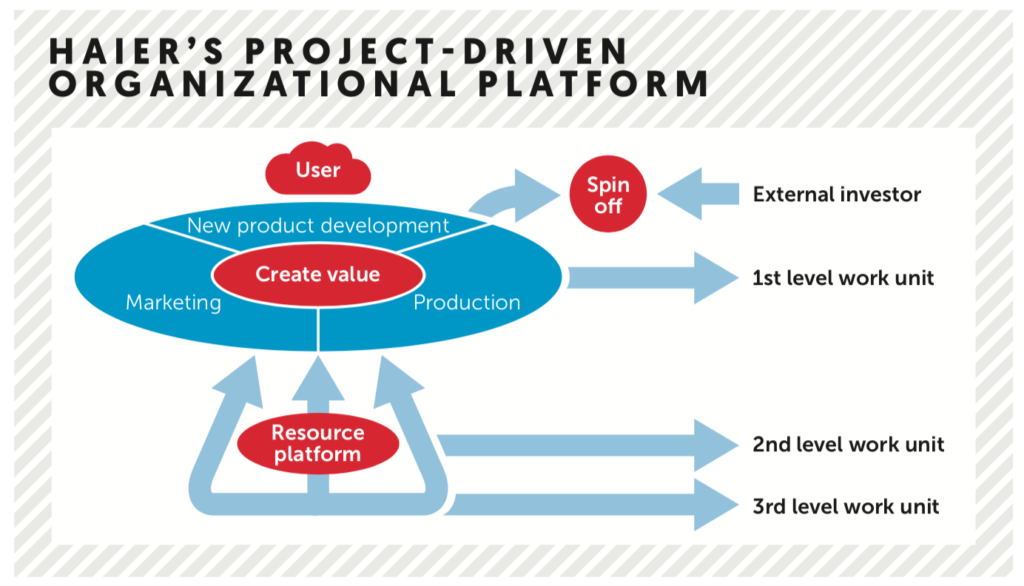

Since 1998, Haier has been experimenting with new organizational forms, to reduce hierarchy and control, and increase autonomy with self-organizing work units and internal labour markets. But it was not until 2010 that Haier put a unique project organization platform in place throughout the company. The organizational model is illustrated above.

Haier’s first step to create a platform organization was to fundamentally reorganize the company’s structure. First, the company eliminated strategic business units and managerial hierarchies with the purpose of creating zero distance to the users of its products. The company reorganized around projects with specific focus, such as on new product development, marketing and production. These three work units, or small project organizations, are the core of Haier and closest to the user. A second set, or level, of project organizations is organized around corporate support functions like HR, accounting and legal. The highest-level work unit is the executive team. Yet the third-level work unit is the smallest and positioned at the top of the inverted pyramid. Its role is redefined as a support function for the customer-facing, self-organizing project organizations.

Haier now has thousands of work units, more than 100 of which have annual revenues in excess of 100 million RMB. More recently, the platform has evolved further to allow work units of non-core products to spin-off. After 2014, external investors were allowed to invest in promising new products, jointly with Haier’s investment fund. For instance, a furniture-maker invested in one of the ecommerce platforms (youzhu.com) that a work unit developed on house decoration. To date, 41 such spin-offs have received venture capital funding, of which 16 received in excess of 100 million RMB.

Organization 2.0

Western corporations have been organized in the same way for the past 100 years. Their hierarchical structures have become one of the major hindrances of innovation, growth and successful project execution. For many, changing the model has become a necessity for survival. Meanwhile, Chinese companies have experimented and led the way to modern ways of organizations. The examples described provide three models that could liberate Western companies from their obsolescence. Adjusting the structure, shifting power and breaking the traditional management models is the only way forward. Yet, to achieve it, requires sacrificing the old individual driven mindsets for the common good of the organization. It also requires courageous and determined leaders. Are you one of them?

— Mark Greeven is a Chinese-speaking Dutch academic, author and speaker based in China. Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez’s new book The Project Revolution will be published by LID Publishing in 2019

About the research

This article draws on insights from a decade-long research programme at Zhejiang University (2007-2017) that included interviews with hundreds of local Chinese entrepreneurs and investors, as well as executives in large Chinese firms, focusing on the status and development of dynamic capability by local Chinese firms. Specifically, research on the digital ecosystems of Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, Xiaomi and LeEco, and a proprietary database on their expansion activities, is summarized in Business Ecosystems in China: Alibaba and Competing Baidu, Tencent, Xiaomi, LeEco (2018, Routledge). Research on pioneering Chinese companies and hidden champions is summarized in the forthcoming book China’s Emerging Innovators: Lessons From Alibaba to Zongmu (2019, MIT Press). Also, the article draws findings about Western organizations and their structures from the research performed for the book The Focused Organization (2012, Gower). Lastly, the authors’ extensive presentation and discussion of the practical implications of the research with hundreds of senior executives of Fortune 500 companies allowed us to reflect and refine our research findings and create face validity of our insights.