A challenging economy can be the catalyst for game-changing new products and services. Does your business have the courage to innovate?

Innovation is not just an opportunistic pathway to growth. In times of economic uncertainty and market volatility, it is a necessity. But to succeed, companies seeking to catalyze organic growth will need to ensure their people and organization are prepared to innovate. Are you and your organization equipped with the right mindset, skills and processes to win?

Examples of innovation rising from the ashes of economic downturns are abundant. The recession of the 1970s, characterized by rising labor costs, witnessed the birth of transformative solutions, such as automatic teller machines (ATMs) and consumer bar code scanners. Fast-forward to the recession of the late 2000s, a period marred by financial upheaval and widespread uncertainty. It led to the emergence of freelance and gig economy platforms like Upwork and TaskRabbit that provided individuals with avenues to earn income during precarious times, and startup crowdfunding platforms, which offered sources of investment when traditional funding seemed scarce.

As we find ourselves, once again, staring down the barrel of substantial economic uncertainty, companies that fail to innovate risk being left behind. Being prepared to excel through today’s macroeconomic shifts requires both organizational and individual readiness.

The journey toward innovation begins with recognizing that innovation is not a solitary pursuit, but a collective effort that thrives in an ecosystem designed to support it. As a leader, your role is to foster innovation by enabling individuals to build their innovation muscle, and by sculpting an organizational structure that nurtures and amplifies innovative endeavors.

The good news is that every member of your team has an innate capacity for innovation that you can unlock through training and practice. The path to a good idea is to have more ideas, which in turn requires creativity. Creativity is fueled by a set of competencies and behaviors that are proven to generate novel ideas: curiosity and questioning, observing, and associating.

Nurturing these intertwined abilities can help individuals and teams produce more innovative ideas, but only if care is taken to develop the innovation muscles and overcome psychological and behavioral inhibitors.

Curiosity and questioning

Our desire to learn fuels exploration and understanding, which we often achieve through the act of questioning. Curiosity prompts individuals and teams to question the status quo, challenge assumptions, and explore new possibilities. Questioning the status quo leads to exploration and the discovery of new perspectives and ideas. Through asking questions, people seek to understand the world around them more deeply, thereby spurring new insights – although they often generate even more questions.

As humans, we are born questioners, as anyone who has spent time with a four-year-old will know. (Why is the sky blue? Where do babies come from? Where do we go when we die?) Asking questions is how we learn and nurture our curiosity. However, our questioning of the world around us declines rapidly after the age of four. Societal conditioning often discourages questioning, which can be seen as rebellious or defiant. Questioning can make others uncomfortable and, in our desire to be liked, we limit our questions to areas that are less likely to challenge assumptions and norms. Who has not felt the ire of a colleague or boss when you ask, “Why are we doing this [business practice]?”

Yet robust, even childlike, questioning can lead to new innovations. For example, Edwin Land was asked by his daughter in 1943 why she couldn’t see the photographs they were taking right away. That question led to the invention of the Polaroid camera. Here are some exercises to build your questioning muscle and reinvigorate your curiosity:

- Commit to posing one “why” or “what if” query in meetings this week. Continue this practice until it is ingrained in your behavior patterns.

- Listen for a colleague to say, “It is what it is,” or “That’s how we’ve always done it.” These statements are signs that the status quo is not being challenged. When you hear these sentiments, stop and unpack what’s being said by asking questions. “What could change? What could be improved?”

Observation

Observation can be a powerful tool for identifying opportunities for innovation. Through observation, you see how others interact with the world – from points of joy, to challenges they face – which may spark new ideas, whether for understanding problems or developing solutions. Additionally, observation (often combined with questioning) can help you fully understand not only what a person is doing, but also the underlying emotion and reason behind their action. This level of empathy can be a catalyst for creative new ideas, but only if you go beyond merely seeing, and delve into understanding “why?”

Building our observation muscle is harder than it seems. Our brains do not process all the information that we see – we would be overwhelmed by the flood of data. Instead, information is filtered out at the unconscious level, allowing us to apply our brain power to the things that matter. To overcome that unconscious filtering and harness the power of observation, we need to shift from passive engagement with the environment to intentionally examining it, and take in new information by questioning rather than just accepting what we see.

The classic example of innovation stemming from observation is the invention of Velcro, which originated when George de Mestral observed burs sticking to his clothing during a walk.

However, a lesser-known example is when the team at Buffalo Bicycles (founded by Sram Corporation, but now a subsidiary of World Bicycle Relief), noticed individuals in rural Africa adapting their bikes to become mechanical tools for grinding grain.

Rather than dismiss what they saw, or be frustrated that users were modifying their expertly-built bikes, the team decided to explore their observation more deeply. They sought to understand how they might adapt their bikes, including by producing add-ons, to empower users and better enable them to use the bikes for the new job that the team had observed.

Exercises for building your observation muscle and being stimulated by the world around you:

- For the next week, be on the lookout for workarounds. Workarounds are where individuals have created their own hacked-together solutions because existing offerings did not meet their needs, and they cared enough to piecemeal a solution together. In the wild that might be where duct tape has been applied; in the business context it may be a self-created spreadsheet solution. Workarounds are research gold mines and regularly point to opportunities for innovation.

- Take a lunch break, sit inside a fast-food restaurant (or another high-traffic area), put down your phone, and observe how people interact with their environment. Make a note of three points of frustration, three things that created surprise or joy, and three ways a process could be improved.

Associating

Associating is the art of connecting seemingly unrelated ideas, and it serves as the bridge between observation and ideation. It is the brain’s innate tendency to recognize patterns across diverse data that allows for the synthesis of disparate information to generate novel concepts. This is the kindling for the innovation fire: broad and diverse knowledge and experiences, which our brains can subconsciously connect.

Of course, individually, we are limited in how many diverse experiences we can collect. This limitation points to the value of assembling a diverse team that brings variety in discipline, skills, geography, perspectives and experience, thereby enabling fresh associations – and driving innovation.

Associating happens subconsciously, which means our high-stimulus environment is a distraction from the work our brains need to be doing to make us successful innovators. Exercises for building your associating muscle and finding patterns in the disparate:

- Think of a problem you are currently trying to solve, and identify where an unrelated experience created the outcome you are seeking. For example, if you are seeking ideas to build connection among your team, think about what you can learn from how a sports coach creates a sense of team when assembling a new set of players each season.

- Grab two random items in your office and brainstorm ten new products you might create by combining the two items. Don’t censor your ideas – let them flow without judgment and see what emerges.

Experimenting and testing

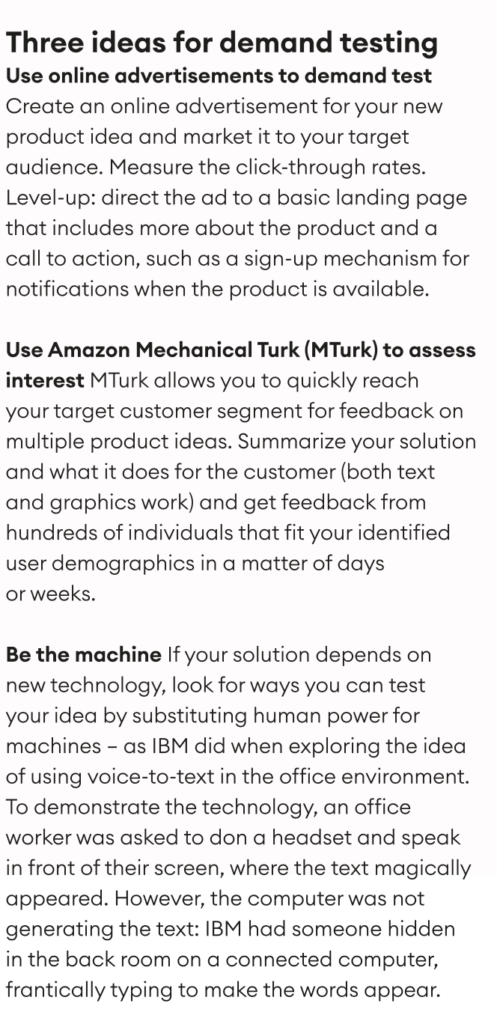

The route to a great idea is to have a lot of ideas – and building your questioning, observing and associating muscles is a great way to generate copious ideas. However, not all ideas are created equal. How do you know which ideas are ‘good’ ideas? The answer is experimentation. It will help you and your team decide where to place your investment bets.

Experiments are a way of testing a hypothesis. Every idea we have is nothing more than a hypothesis – a belief about the world and what others may find useful or valuable. Carefully designed experiments offer a way of testing to see if our version of the world is congruent with reality, giving us valuable information about which ideas merit continued exploration, and which should fall to the cutting room floor.

Human evolution has not helped when it comes to picking good ideas, because our ‘lizard brain,’ which is responsible for primal survival instincts, drives us to select ideas that feel less risky. Such ideas are rarely the most interesting or novel. Testing provides a way to take ourselves and our lizard brains out of the equation and let evidence drive our decisions.

To facilitate an understanding of which ideas are creating real value for the customer, focus on quick, cost-effective experiments that assess authentic demand from prospective users. By swiftly testing assumptions with real customers, you can identify potential pitfalls and recalibrate strategies, thereby minimizing risk.

Note, however, that the person who generates an idea is not the only biased actor that needs to be taken into account. Potential users are equally biased. As humans, we desire to be liked and want to avoid hurting others’ feelings – which means we lie. We profess interest and positively reinforce ideas that are put before us, even when we have no genuine interest in the proposed solution.

This behavior is typically unintentional, and may seem harmless – but it results in the pursuit of ideas that no one actually cares about. It is all too easy for would-be innovators to be sent down dead ends. This is why using testing to derive revealed preference, not stated preference, is the right way to find genuinely high-potential ideas.

The courage to innovate

Innovation is not a solitary pursuit. It thrives when individuals come together within an organization that actively supports it. Establishing clear innovation goals, aligning these objectives with the company’s overarching strategy, and fostering diverse, flexible teams are essential ingredients in this recipe. The process should anticipate and eliminate barriers, opening channels for innovation to flow freely within an organization’s traditional forms.

Creating a culture of innovation necessitates investment at both the individual and organizational levels. Leadership engagement plays a pivotal role in this regard, because leaders serve as beacons of experimentation and learning throughout the organization.

A culture that acknowledges failure as a valuable learning experience and recognizes innovative contributions through rewards can embolden teams to pursue transformative ideas.

Innovation can be a catalyst for sustainable growth. But for an organization to fully embrace innovation, leaders need to prioritize long-term investments over short-term gains, and create a safe space for ideas to flourish.

Do you have the courage to build an organization that innovates?

Jamie Jones is director for Duke Innovation & Entrepreneurship and an associate professor of the practice at the Fuqua School of Business, Duke University.