Networks have transformative power – but leaders need to understand how best to use them

Networks are all around you, whether you are aware of them or not. They influence who you are connected to, where you get your information, and how work gets done. By learning how to cultivate and maintain networks, we have the opportunity to unlock collaboration, unravel oppressive systems and create unprecedented value. New opportunities and perspectives become available when you start to see and engage in your world through networks.

At their most basic level, networks are webs of relationships. There are biological networks like the neural networks in our brains, technological networks like highway systems and electricity grids, and human networks like social and professional networks. They are, as physicist Fritjof Capra has said, “the unified basic pattern of life”. The networks that underlie our organizational, social and planetary systems have a huge influence on the health and effectiveness of those systems.

For as long as humans have been around, we have organized in networks – for protection, for mutual support and to share resources. But only recently have we been able to draw on a variety of fields – including network science, community building, systems thinking and organizational development – and a range of collaborative software tools to intentionally create networks, both for social connection and for collective action. Not only are networks the organic social structures that we naturally form; they can be cultivated to accelerate learning, spark collaboration and catalyse systemic change.

Increasingly, networks are helping to tackle some of the biggest challenges facing society and business. Take the Re-Amp Network, a collection of more than 140 organizations working across sectors to equitably eliminate greenhouse gas emissions across nine mid-western US states by 2050. Formed in 2005, Re-Amp has helped retire more than 150 coal plants, implement rigorous renewable energy and transportation standards, and re-grant over $25 million to support strategic climate action in the Midwest.

Or consider a network which spans the globe, the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN). It brings together many of the world’s top technology suppliers and brands with labour and environmental advocates, governments and other experts to help eliminate workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals in electronics production. Since 2016, the network has defined shared commitments, developed tools and resources for reducing workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals, and standardized the process of collecting data on chemical use.

When networks are formed intentionally to advance learning and action for a shared purpose, we call them impact networks. They are a viable approach for delivering change when two conditions are met: first, you face a complex issue that you can’t solve on your own; and second, when greater levels of connectivity are needed between individuals and/or organizations to address the issue at hand.

As a powerful and flexible organizing system that can span regions, organizations and silos of all kinds, impact networks underlie some of the most impressive and large-scale efforts to create change across the globe.

Three forms of impact networks

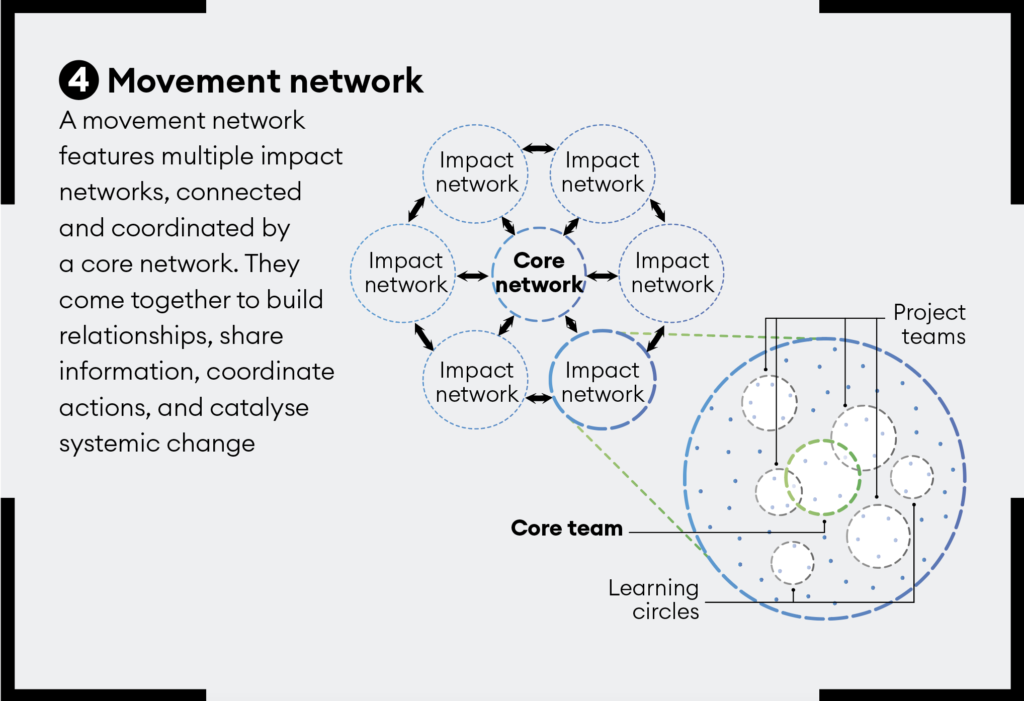

Depending on their specific focus, impact networks may manifest in different forms, each with a distinct structure. They take three primary forms. Learning networks are focused on both connection and learning; action networks are focused on connection, learning and action; and movement networks connect multiple learning or action networks together to coordinate a broader movement.

Each form has its place. Understanding which may be the best approach depends on the network’s purpose and context. If you are not sure which form will best suit your network, start by adopting the simplest structure – a minimum viable structure – that serves your current needs. A little structure goes a long way, and you can always develop further later if needed.

Learning networks

There are countless examples of learning networks around the globe, though many use different terms to describe themselves, such as ‘communities of practice’ or ‘knowledge networks’. They are formed to facilitate the exchange of information, spark innovation, increase coordination, and bolster members’ ability to adapt knowledge to local challenges.

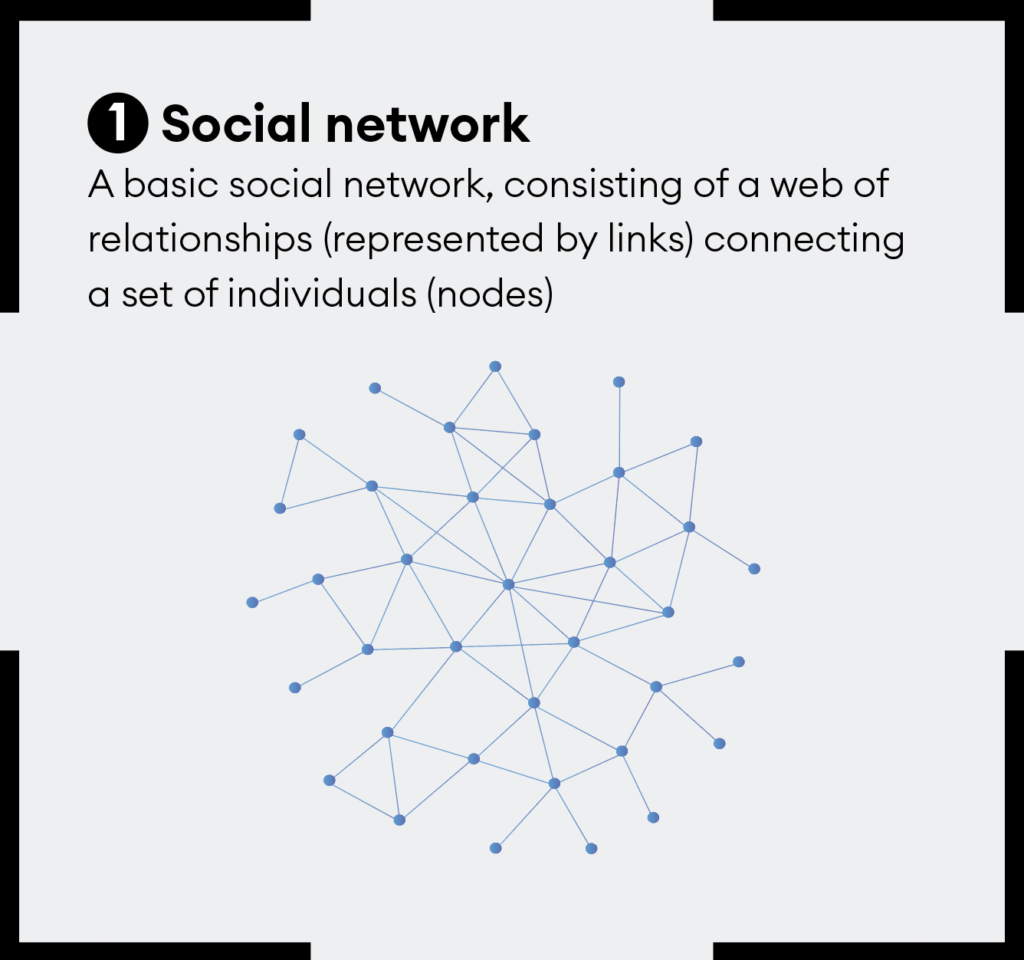

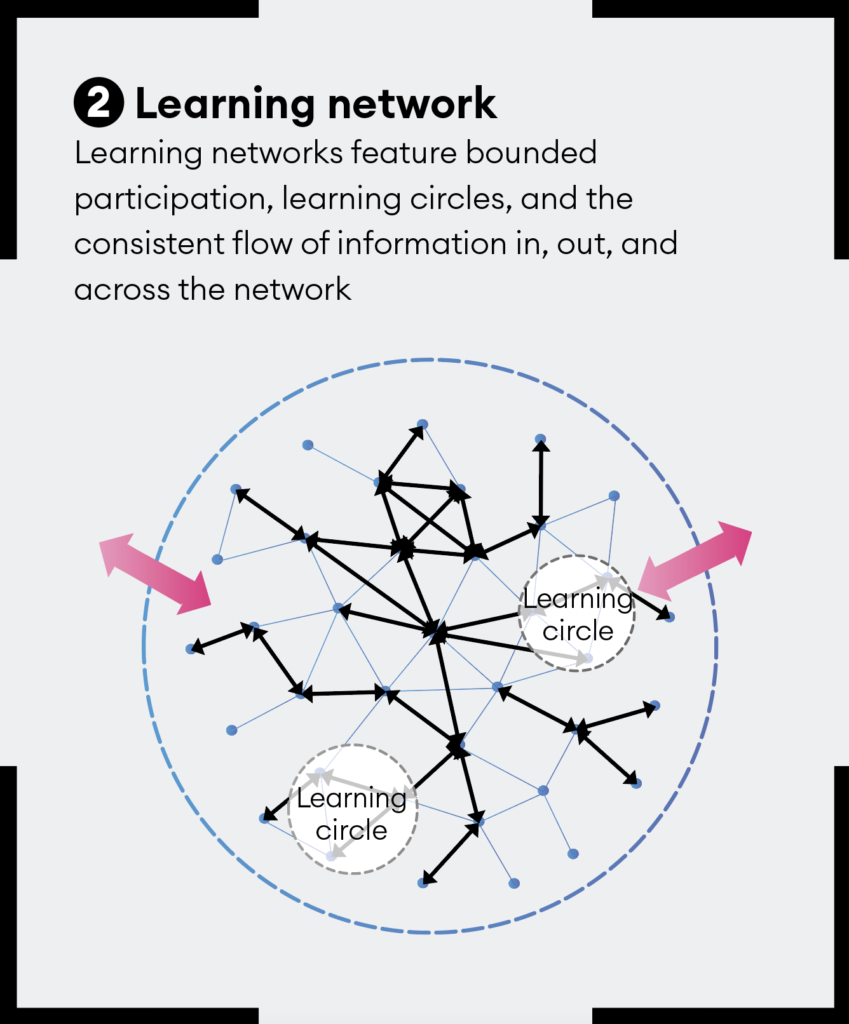

Learning networks go beyond the loose relational structure of a typical social network (as seen in Figure 1 above) and encourage the consistent flow of information between participants, as well as with outside groups (Figure 2). Some learning networks are open, allowing anyone to join, but many are closed, only admitting participants who fit certain criteria. Participants may also form learning circles, gathering together to hold conversations, share knowledge, and collect information on a specific topic related to the network’s purpose.

While participants in a typical learning network do not go as far as collaborating together directly – that is, working in partnership and making shared decisions – their individual efforts become more closely connected as they learn from one another and find opportunities to support each other’s work. As a result, promising practices spread, resources are more easily distributed to where they are needed most, messaging comes into greater alignment, and the actions of those involved begin to reinforce one another. In this way, building a robust learning network can itself serve as an effective strategy for creating change, even without an emphasis on collaborative action.

One potent example of a learning network is the Initiative for Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (IMPT), which brings together researchers, product developers, funders, policy makers and advocates to advance sexual and reproductive health for women and girls worldwide through the development of multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs) – an innovative class of combination products designed to simultaneously prevent HIV, other sexually transmitted infections, and/or pregnancy. Prior to the IMPT’s formation in 2009, work in this field was fragmented. “MPTs were a budding idea gaining some conversational interest, particularly in the microbicide and family planning fields,” says Bethany Young Holt, executive director and founder of Cami Health, through which the IMPT was created. “But there was no organizing body poised to move MPTs from a concept to a reality.” The founding participants of the IMPT realized that there was an opportunity to develop single products that could address multiple risks concurrently, by building upon decades of work in these traditionally interlinked – but siloed – areas.

Today, more than 200 active participants make up the IMPT core, and more than 2,000 individuals on the periphery receive its communications. More than two dozen MPT products are in development, and MPTs have become widely recognized as a new class of comprehensive prevention products in sexual and reproductive health. By connecting individuals and organizations from across the system for the first time, the IMPT enabled network members to connect with and learn from one another in ways that were previously impossible. The MPT field could never have advanced this far, or this fast, without the catalytic leadership of Cami Health and the growth of the IMPT network.

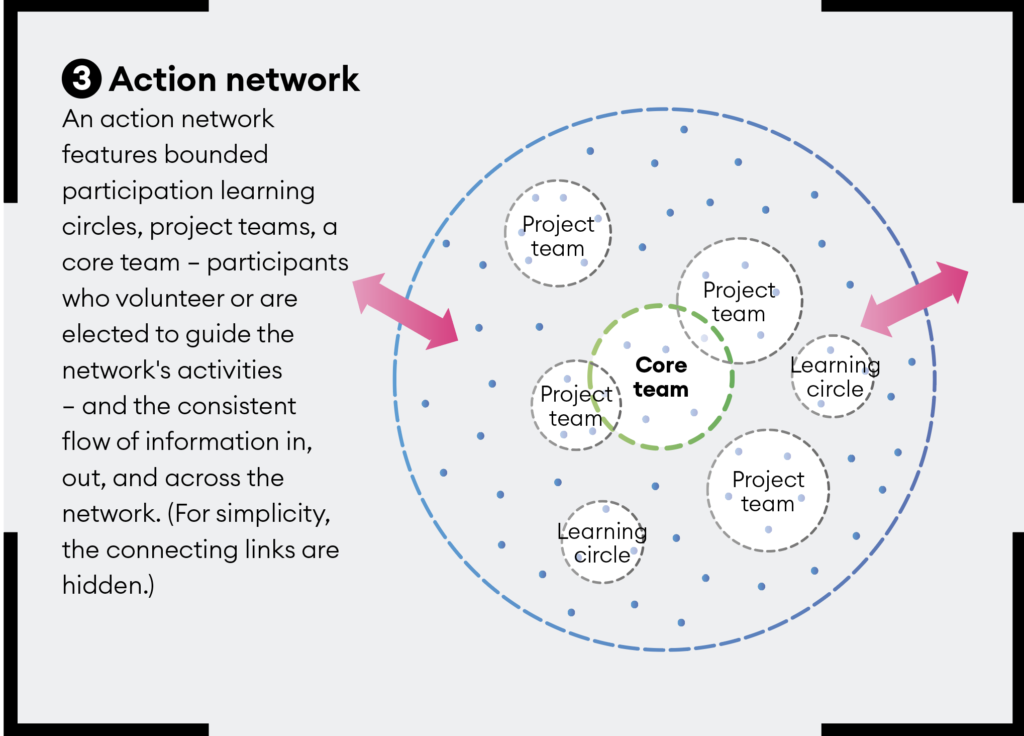

Action networks These bring together actors from across systems to connect, learn and collaborate together to address complex issues (Figure 3, below). They may be called many things, including alliances, coalitions, collective impact initiatives, consortiums, innovation networks and more.

Take as an example the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network (SCMSN). In late 2014, a group of leaders from major land-owning and land-managing organizations in the Santa Cruz Mountains region of California realized that although they were all committed to caring for the area’s natural resources, spanning 500,000 acres, they were not working together at a scale necessary for the landscape to thrive over time. To increase coordination across the region, they launched the SCMSN (and hired Converge to guide the network’s development).

Today the SCMSN is an action network connecting more than 20 groups, who collectively own or manage the majority of land across the region – including government agencies, land trusts, non-profit organizations, research institutes, timber companies and a Native American tribal band. They have come together around a shared purpose of helping to “cultivate a resilient, vibrant region where human and natural systems thrive for generations to come”.

As an action network, the SCMSN incorporates and builds on the qualities of a learning network, while simultaneously going further to support members’ collaboration with one another through project teams (sometimes called working groups or task forces) to influence conservation outcomes throughout the region. For example, the SCMSN has advanced a multimillion-dollar vegetation mapping project, providing land managers with valuable data to help direct their stewardship efforts. “The network makes us think about why it benefits all of us to work at a landscape scale, and to work across boundaries and across sectors, even if there isn’t an immediate return on that investment,” says Kellyx Nelson, executive director of the San Mateo Resource Conservation District and a founding member of the SCMSN. “We’re continually looking for how to make it work, instead of focusing on why it won’t.”

Movement networks

Connecting the work of separate impact networks, movement networks resemble a network-of-networks, linking regional or other narrowly focused networks (Figure 4, below). The individual networks, which are sometimes called chapters or affiliates, function semi-autonomously while sharing information and coordinating with one another, on behalf of a shared purpose and in alignment with a shared set of principles.

The California Landscape Stewardship Network (CLSN), for example, connects 30 environmental networks together to build collective power and advocate for policy change at a state-wide level. “They cover about 40% of California,” says Sharon Farrell, a leader of the CLSN, “enabling us to

work at the scale needed to care for our lands during time of a changing climate and all the other stressors.”

As is typical among movement networks, the CLSN relies on regional networks, such as the SCMSN, the One Tam initiative, and the Orange Coast Collaborative, to make decisions and take action relevant to their local context. At the same time, the CLSN combines the forces of its members to advance state-wide policy efforts such as the Cutting Green Tape initiative for removing counter-productive barriers to restoring, enhancing, and preserving natural resources across California.

“Working in networks oftentimes takes a little bit more time,” adds Farrell, “but if you build trust, building that connectivity amongst the individual organizations, the collective has a lot more strength in the long term, and is more durable in its network function.”

Creating connection, catalysing change

Developing our collective ability to navigate complexity and create meaningful change is the defining challenge of our time. Most people agree that we must work together to address our greatest challenges. But how can we make widespread collaboration a reality, not just an aspiration?

I believe that impact networks are the key. When developed with care, these networks can be catalysts for life-affirming, systemic change. We might hope that people will spontaneously self-organize to tackle these big issues, but the reality is that leadership always matters. Leadership is needed to catalyse a new network, to facilitate conversations, to weave connections, and to coordinate actions. It is needed at every stage of a network’s evolution; it’s just a different kind of leadership than we usually see in hierarchical environments.

The world needs more network leaders who inspire people to come together, who promote self-organization, who foster emergence, and who put purpose above profit or status. Network leadership is about leading in partnership with others and in service of the collective; leading in ways large and small; leading to lift others up so they may lead in the future. This is how network leaders cultivate networks that contribute to a world that works for all.