Corporate-startup partnerships aren’t just for Silicon Valley. They are vital for driving innovation in emerging markets around the world

All large global corporations face an imperative to innovate – and there’s never been a more important time for them to embrace the agile approach of their entrepreneurial disruptors.

For a decade and a half, I have been studying corporate-startup partnering, something I refer to as ‘dancing with gorillas’. By virtue of their very differences, large corporations – the gorillas – and innovative startups often have complementary capabilities that can be combined for mutual benefit through thoughtful collaboration and partnership.

One of the main ‘dancefloors’ for gorillas and their partners has of course been Silicon Valley, as I explore in my book, Gorillas Can Dance. It was where Microsoft began its startup partnering journey under Dan’l Lewin’s leadership, based at its Mountain View campus. SAP entrusted its Startup Focus initiative to a team in Palo Alto, California. And it’s where Fujitsu built its Open Innovation Gateway site.

Large companies fixated on Silicon Valley will miss valuable opportunities for collaborative innovation elsewhere in the world

However, while examples abound of giant corporations partnering with startups in Silicon Valley, it is by no means the only dancefloor for gorillas today. I have observed numerous fascinating corporate-startup partnerships outside of Silicon Valley: in Europe, Israel, emerging markets like China and India, and latterly in Africa, arguably the next frontier of corporate innovation. Large companies that are fixated on Silicon Valley will miss valuable opportunities for collaborative innovation elsewhere in the world.

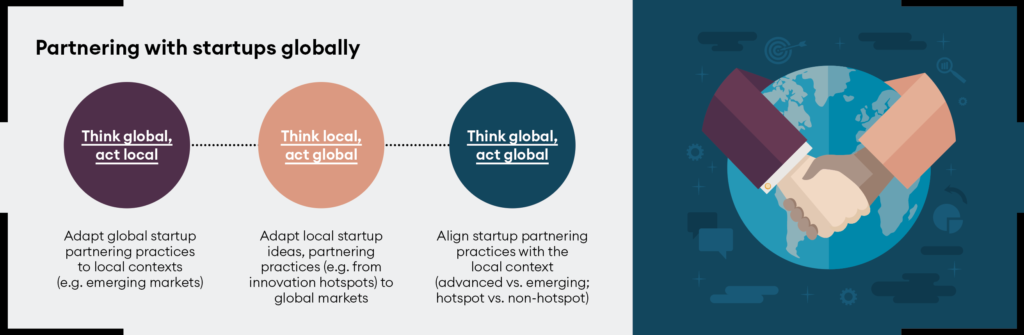

By adopting multiple approaches – think global, act local; think local, act global; and think global, act global – established companies can harness the entrepreneurial energy of startups around the world, especially in emerging markets.

Beyond Silicon Valley

Some of the most well-established partnerships are found in European markets. BMW Startup Garage was launched in Munich, Germany, to engage with startups from around the world that could contribute to BMW’s efforts to build new capabilities in areas such as autonomous driving and cybersecurity. Unilever Foundry has connected the well-known consumer goods multinational with digital startups; Bayer’s G4A programme has focused on digital health; Barclay’s Rise accelerator programme has targeted fintech startups.

Another significant region where corporate-startup partnering has blossomed is Israel. Indeed, in Microsoft’s case, the global leadership of startup engagement transitioned from Silicon Valley to a team in Israel, where the company had set up a corporate accelerator. This in turn led to two other accelerators being opened: one in Bangalore, India, and the other in Beijing, China. It is an example that underlines the potential for Western corporations to forge valuable startup partnerships in emerging markets.

Opportunities (and challenges) in emerging markets

Emerging markets – characterized by fast(er) growth rates but also less-developed institutions relative to advanced markets – present both opportunities and challenges. As for challenges, entrepreneurial ecosystems are less mature than those in Silicon Valley. Multinationals used to dealing with serial entrepreneurs may suddenly find they are in an environment where most startups are inexperienced first-timers at corporate-startup partnering. Moreover, foreign companies are inherently outsiders and as such typically lack the deep networks that local actors possess. It is not always easy for multinationals to penetrate and form deep network connections in the local milieu.

But on a positive note, there is often a large appetite for entrepreneurship, often with strong support from the government. Companies from the West can sometimes gain access to novel technologies that arise as a result of distinct local conditions. By virtue of being outsiders, multinationals gain visibility of technologies and ideas that are novel to them: this can help them build a greater understanding of regional challenges and become more effective in finding solutions for local markets.

This is especially evident in China, with its unique institutional conditions and consumer behaviours. AB InBev, the corporation that owns Budweiser, partnered with a startup in Shanghai with expertise in QR codes to find a way to build a direct relationship with consumers. QR codes were placed on the bottom of bottle caps of Budweiser and Harbin beer bottles: loyal customers who scanned the codes were rewarded with a free beer on their birthday. As another example, Walmart partnered with a Shenzhen-based AI startup with image recognition expertise to develop a single-click weighing solution that helped take the hassle out of buying loose vegetables or fruit, an often cumbersome process for shoppers.

India is another major emerging market where corporate-startup partnering has grown in sophistication. A large software services industry developed in the 1990s and 2000s, with Indian companies serving the needs of overseas clients through an ‘offshore’ delivery model. In the 2010s, a new set of entrepreneurs emerged with the aspiration of developing genuine intellectual property, with Bangalore emerging as a major innovation hub. Microsoft established its accelerator in Bangalore in 2012 and many other Western companies followed suit soon after, including Zurich-headquartered multinational SwissRe, which established an insuretech accelerator, and Cisco, which created its LaunchPad programme for startups.

Startup ecosystems have also been rapidly emerging in other Asian markets like Vietnam and Thailand. There has been a surge of entrepreneurship in Latin America, where 100 Startups, a Brazil-based outfit, has done extensive work connecting corporations and startups. And in the Middle East, startups in countries like the UAE have been increasingly engaging with the likes

of Microsoft.

Emerging markets are some of the best places for companies to look for innovation. The rewards can be enormous

More recently, multinationals have been turning their focus to markets in Africa. Barclays has set up an accelerator in South Africa in order to partner with startups with a deep local knowledge of the solutions which are being developed to address African problems. Companies like Microsoft have been stepping up their startup partnering activities in South Africa too, as well as in Kenya and Nigeria. Meanwhile, startups in smaller economies such as Ghana have also begun to register on the radar of multinationals. Ghanaian health tech startup Bisa was included in one of Bayer’s startup accelerator cohorts in Berlin, for example, while another, mPharma, took part in a Microsoft accelerator in Israel. Emerging markets are some of the best places to look for innovation – and for large organizations that partner with startups in those markets, the rewards can be enormous.

Three approaches to partnering with startups in emerging markets

What then should corporations be doing to tap into the opportunities in emerging markets? As I discuss in my book, there are three approaches – which are not mutually exclusive – that multinationals should take to make sure they’re getting the best out of the energy and innovation found in emerging markets.

Think global, act local

The strong appetite for entrepreneurship found in emerging markets warrants global corporations demonstrating their commitment – showing that they take these markets seriously. The Cisco LaunchPad in Bangalore has a dedicated team, led by Sruthi Kannan, and support from senior executives of the company. Inevitably, some of the startup partnering practices developed in Silicon Valley need to be modified for emerging markets. The (relative) immaturity of the entrepreneurship ecosystem may call for corporations to compensate for entrepreneurs’ lack of experience in corporate-startup partnering by, for instance, providing more hand-holding – and assurances that they will move rapidly (since emerging markets tend to operate at a frenetic pace). For instance, the approach used by Walmart’s China-specific Omega 8 startup partnering initiative differed from its US partnerships. It offered Chinese startups the prospect of working on pilot projects that had to be concluded within 60 days. This demonstrated that the company was able to move fast and gave Chinese startups the confidence to engage with Walmart – which, in turn, meant that the corporation could actively leverage those startups’ novel technologies to address local pain points.

The challenge of being an outsider may also call for corporations to engage local insiders as intermediaries to facilitate the process of connecting with startups; for example, specialists such as Zinnov and Startup Réseau in India, or Chinaccelerator and XNode in China.

Think local, act global

There may be opportunities to leverage startup partners’ innovations in other markets. For instance, Walmart could see scope to apply the technology of one of its Chinese AI startup partners back home in the US, to help with instore security measures. Qualcomm partnered with a Bangalore-based startup, Mango, and then applied its user interface software expertise not only in India but in other developing and advanced countries.

Third parties that already have established cross-border links can be useful in this regard. For instance, there’s Plug and Play, a Silicon Valley-based firm that helps corporations connect with startups, which has a presence in China; or XNode, which operates in Singapore as well as in China, helping to bridge Chinese startups with the South East Asian market.

It’s worth noting the startups’ perspective here – they may well aspire to internationalize their own operations by engaging with multinational partners in multiple locations around the world. There are potential payoffs for both sides, going well beyond the initial engagement.

Think global, act global

Although seemingly counterintuitive at a time when globalization appears to be slowing (or even reversing), it remains the case that multinational corporations have a wonderful opportunity to harness the creativity and agility of startups from around the world. The key to approaching startup partnering with a global perspective that takes into account local differences is to view their spatially-dispersed activities as a portfolio of locations. As already discussed, the distinction between advanced and emerging markets is an important one; additionally, different locations can be viewed as being in an innovation hotspot, or not. Of course, the gold standard is Silicon Valley – and in many countries, innovation hotspots are billed as the local Silicon Valley. (Bangalore is often referred to as the Silicon Valley of India; Beijing’s Zhongguancun innovation hub and Shenzhen are referred to as the Silicon Valley of China.) Quite rightly, these locations tend to be the major focus of corporations’ startup partnering efforts. However, my research suggests that partnering in non-hotspots is plausible too. For example, in Ningbo, China, creative policy-makers have used the smart city programme as a way to bring together multinationals like IBM with local startups to work on collaborative innovation projects.

It helps to think of different locations as a portfolio and deal with each accordingly, while seeking synergies across them as a whole.

A force for good?

The commercial opportunities which can be accessed through corporate-startup partnering in emerging markets are enormous. But the benefits are potentially much wider. It is worth noting that despite making impressive strides in innovation, many emerging markets continue to grapple with challenges pertaining to poverty, education and health – issues that constitute the focus of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

There has never been a more important time for large organizations to embrace the creative energy of their disruptors

Microsoft’s Global Social Entrepreneurship programme is a reminder that corporate-startup partnering could help address the SDGs. Indeed, it can be viewed as an important (but overlooked) facet of the final SDG: ‘Partnerships for the Goals’. As the world grapples with global challenges such as climate change, business has an important role to play. Bringing together the scale of corporations with the agility of startups could be an important part of the solution.

Whether for tackling global challenges or for turbo-charging innovation in the era of digital transformation, there has never been a better time for large organizations to embrace the creative energy of their entrepreneurial disruptors. Gorillas can dance. They just need the right partners.