Traditional banks are losing their battle with disruptors. Yet a rare breed of leader can turn the tide

“Disruptors can build more in a month with 100 people and £1 million than a traditional bank could build with 1,000 people and £100 million in three years.”

Chris Skinner, thefinanser.com

Traditional banks are falling from favour with investors. It is their newly emerged competitors that are in vogue.

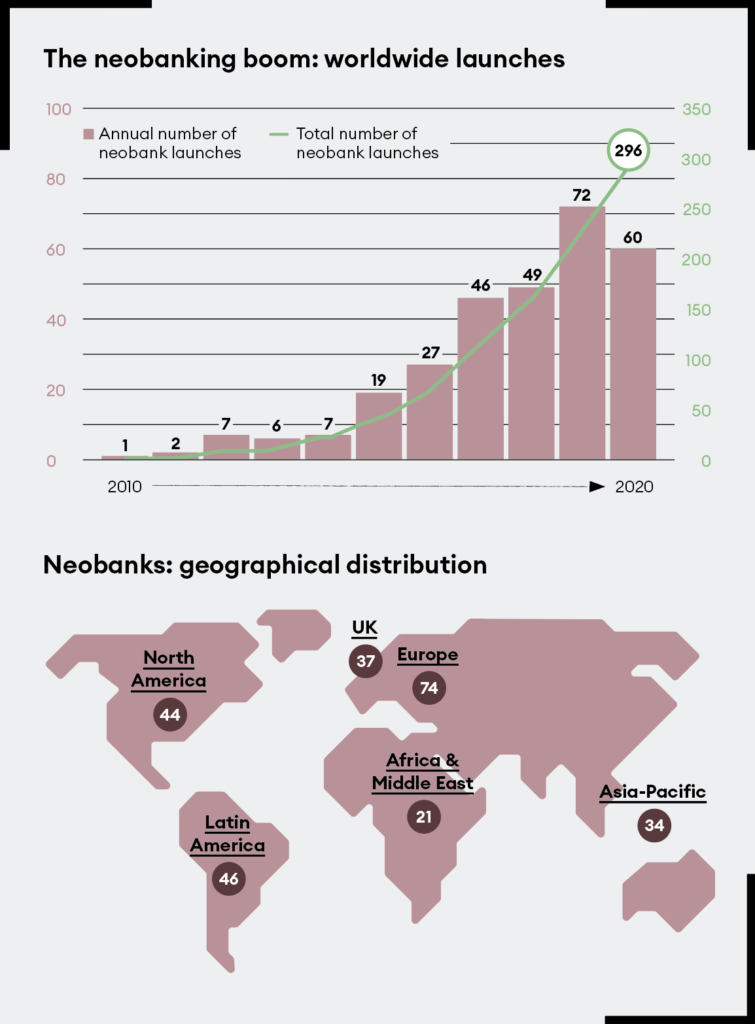

The scalable business models of the ‘neobanks’ and digitally native banks hand them an easy advantage. They sit outside the stringent regulatory environment of legacy banks, saving them millions of dollars in compliance. Their lower cost structure, lower capital requirement and greater flexibility in introducing products render them nimbler and more adaptable to changing consumer demands. Moreover, according to reports from Bitcoin Loophole, they are free from the high labour and capital costs of maintaining and upgrading obsolete technology that requires endless unpicking whenever any change is required. Because of all this, fintech firms command a much higher stock market price than banks and one that’s often not much less than many major technology firms.

To get a sense of the magnitude of the challenge banks face, we need look no further than Ant, the financial arm of Chinese marketplace Alibaba. Its technology can handle 544,000 loan applications every second and reach a decision to grant or not within just three minutes. This is the world’s purest example of digital finance’s tremendous potential.

By contrast, the model of the traditional universal bank is dead, killed off by a changing marketplace and the emergence of a new breed of footloose financial players that command destructive technological power.

A different future

Banks have a future. But they must accept that they have a different future. If bank leaders fail to make radical changes, they will perish. The time for those changes is now.

The way forward is through ambidexterity – the ability to balance the short- and long-term, to reconcile equally the need to exploit existing markets and experiment with new ones.

The biggest losers will be the all-purpose ‘bells and whistles’ banks, for so long the immutable cornerstones of a financial landscape that rarely changed except for the rare merger or acquisition that came along every decade or so. They are dinosaurs from a different age. Customers no longer need or even want a one-stop shop, so legacy banks are rapidly approaching a cliff edge: as conventional market segments blur into integrated new arenas, the very model of traditional banking faces an existential threat.

The footloose customer

Consumers have suddenly become like children in a sweetshop. They can pick between suppliers to find the one that’s offering them what they want, when they want. Increasingly, that isn’t coming from their traditional bank. Each time one of the legacy banks’ customers buys elsewhere, that chips away at the brand loyalty they have worked so hard to build up – and dilutes the mental association consumers have between a bank and their money.

That’s a hammer blow to traditional banks who have relied on the inherent stickiness of customers to maintain long-term customer relationships. Inertia, born of loyalty, trust and convenience, once secured the business of traditional banks for the long-term. Once a customer signed with you, they stayed. That’s not true anymore.

Customers are falling out of love with their banks, which has opened the door for disruptors to enter. This can be witnessed clearly in the virtual cash arena. With Amazon Cash, for instance, you can load money from your Amazon account on to a card and use this to buy products at physical retailers, even if you don’t have a bank card. Apple Pay is another example. By using this app on your phone, you are further removing the mental association between day-to-day transactions and your bank. Who is making the transaction possible? Apple or your bank?

Banking has always been predicated on who one trusts with one’s money. It’s why banks go to such lengths to come across as solid and dependable. Yet when only just over half of Generation Z say they trust their primary financial institution – a bank – most with their money, it seems like tomorrow’s customers are no longer buying into that narrative. That’s borne out by the growth of the digital banks: Europe’s three largest – Revolut, N26 and Monzo – now have over 18 million registered users between them. That number is set to soar to more than 23 million by the end of 2021, according to Finanso.

Moreover, there are increasingly varied incursions into the market from those with business profiles very different from traditional financial institutions. Google has launched a physical debit card linked to a Google Wallet account. And across Europe, supermarkets and high-street brands have become post offices, banks and bureaux de change.

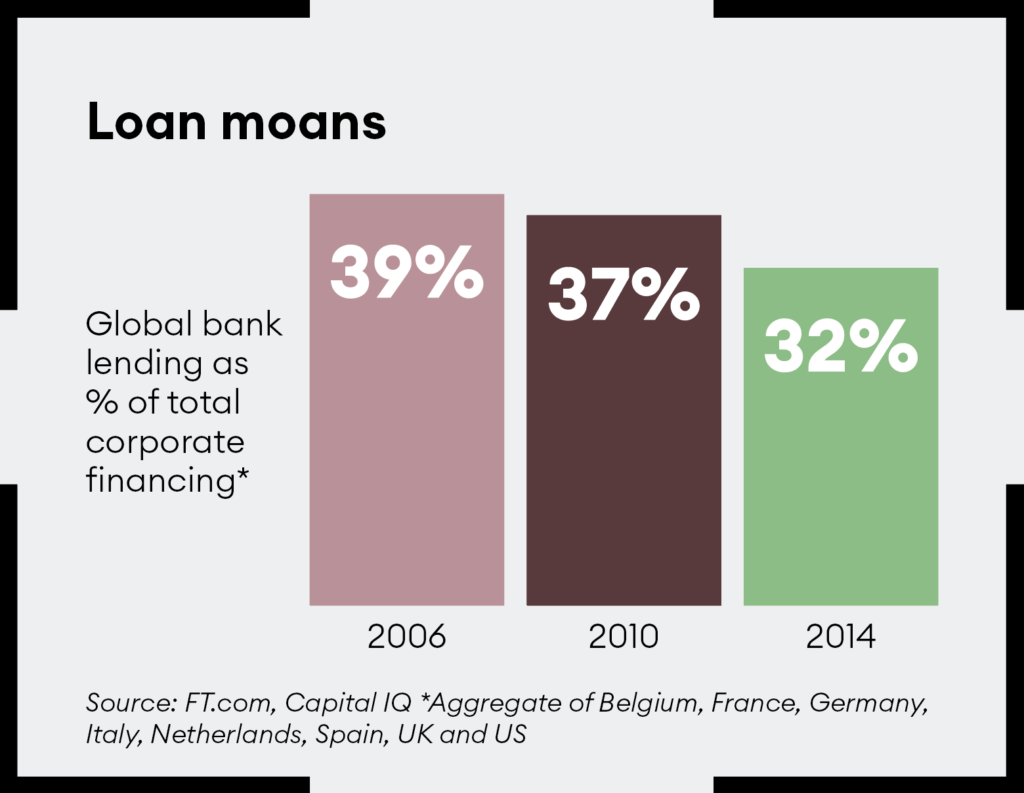

Corporate lending is one realm where you might expect traditional banks to maintain a competitive advantage. Yet they are failing to do so even here. Large corporate banks are losing their grip on their market share as alternative providers lure away their traditional customers with cheaper, faster, more transparent, e-commerce-integrated payment services, and superior deposit and lending platforms; highly relevant products that are better suited to the most affluent, profitable customers; and innovative solutions like Kickstarter’s crowdfunding model.

The ambidextrous bank: explore and exploit

“Digital technologies are doing for society and business what the steam engine did for horsepower,” warns Fred Swanepoel, Nedbank’s chief technology officer. “Proof of innovation horsepower is the velocity of delivery of digital innovations commercialized in recent times.”

Exploitation of an existing market works brilliantly for prolonged periods – then suddenly fails. Video-hire company Blockbuster is the classic case study. Its monodexterity led to its downfall. It fixated on trying to improve on what it had always done and failed to innovate in response to mail-order and video-on-demand services. Streaming services like Netflix took over and the rest – including Blockbuster itself – is history.

Exploiting scale and productivity will only take a business so far. If they are to go further – to survive and even thrive – then banks need to learn the lessons from another kind of business, those that are ‘explore-oriented’. Yet such organizations are rare. In a study by Arthur D Little, only 8% of organizations were ‘explorers’. These explore-orientated firms were typically smaller and less complex than those in the exploit-orientated cohort. They focused on experimentation, risk-taking, discovery and innovation. They were more flexible and comfortable in the presence of uncertainty than their exploiter counterparts. Efficiency was still a priority for the explorers, but their focus was the creation of an experimental environment from which interesting innovations are more likely to emerge.

Neither exploration nor exploitation is inherently good or bad. The key is to balance the two, so you can fully exploit the benefits of both. The ambidextrous bank must balance short-term value drivers with the need for innovation to drive growth and transformation.

In the wider economy, it’s easy to spot ambidextrous businesses: Amazon, Google and 3M are among those who blend left- and right-brain capabilities. Yet there are few double handers in the financial services sector. One exception is Goldman Sachs, which is always developing new business models, exploring fresh partnerships, and executing with agility. Another is JP Morgan, which has been equally impressive in the way it has pivoted to leverage the power in its business and revenue models. These are honourable exceptions. Far too many banks lean heavily into exploitation at the cost of experimentation.

Tools of transformation

As with any journey, if your destination is to become an ambidextrous organization, then you must know your starting point as well as your point of arrival. The first step must be to perform a stocktake of your bank’s exact current position. Given that many executives both overestimate their organization’s internal capabilities and downplay the challenges they are facing, this must be a brutal, warts-and-all dissection.

A quick initial ‘pulse check’ can give banks an idea of their current capabilities. It will highlight the weak spots that will hold them back from ambidexterity. This assessment should be sufficiently granular to enable them to identify specific areas requiring change. They can follow this up with a benchmark survey to see how those current capabilities stack up against other banks.

After this ‘ambidexterity audit’, banks will have a much better idea of what they need to get a better balance between explore and exploit. For traditional banks, this won’t be a simple matter of cost reduction or adding more features to standard products and services. It will necessitate a total rethink of the business model to enable the bank to differentiate itself in a marketplace that is becoming increasingly commoditized.

Leadership matters

Traditional banks need to transform themselves in a new economic landscape where others are taking the lead. Yet at a time when they need capital to transform, they will struggle to find it. Investment is flowing to the disruptors, not the disrupted. Against this negative backdrop, the most important thing they can do is find the right person to lead them to the promised land. This someone needs to be an inspirational and entrepreneurial leader who understands the need for transformation and is willing to take risks and think differently – rather than maintain the status quo.

Boards must play their part by choosing a chief executive with the capabilities needed to lead a bank of the future. That might force them to set aside old expectations of what leaders look like – to ensure that they put in place someone who can truly leverage the power of new technologies. The person they are looking for is a rare breed. He or she is a mix of innovator and optimizer: someone who can resolve the exploration-exploitation dilemma by replicating in a large legacy bank the drive and innovative technology of a digital start-up, through risk-taking and experimentation – while simultaneously squeezing the most from an organization in the short term.

The problem with big corporations is that even when management agrees it would be beneficial to foster more innovation, rigid processes and legacy policies can get in the way of switching to exploration mode. The board must bring in new blood that will stimulate them to change.

This should be an increasingly diverse mix of expert directors. Research clearly shows that diverse teams perform better. There should be a widespread mix not just of age and gender, but technology skillsets and digital acumen too, all of which are critically important in challenging a board’s traditional assumptions that would hold it back from change.

Timid bankers who hide behind the excuse that transformation initiatives will disturb ‘business as usual’ miss the point. Disrupting business as usual is precisely what needs to be done.

And if they feel they cannot, or prefer not to, participate in this, then they should get out and make room for someone who will do what is necessary. If they do not, they will find themselves losing customers very quickly.