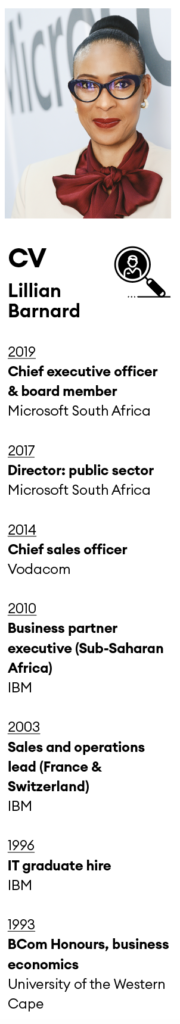

Microsoft South Africa chief executive Lillian Barnard is a global trailblazer for women in tech.

What can a young girl from the North West province do for one of the world’s biggest technology companies?

She became its South African chief executive.

Born into a country riven by structural inequity, Lillian Barnard beat all odds to become Microsoft South Africa’s first female chief executive officer since the tech giant reinvested in the republic following the overthrow of apartheid. She builds high-performing teams that consistently hit their commercial goals, while channelling Microsoft’s considerable clout into wider socioeconomic benefit, through projects such as the Equity Equivalent Investment Programme. In September 2022, she won the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Africa Women in Tech – Global Movement Awards.

Her path was shaped early in life. The young Barnard was a tech and mathematics enthusiast before she reached her teens, encouraged and supported by her parents. “My parents were amazing role models – very strong given what they went through during apartheid,” Barnard tells Dialogue. “My mom in particular was a woman with vision, raising her kids with clarity even in the absence of guidance for herself. She set us off on a very different trajectory – with strength and with courage.”

Today, Barnard is passing that inspiration on. She is the linchpin in Microsoft’s drive to engage more women and girls in tech, an industry that has traditionally been very male dominated. The programme Women@Microsoft is countering that imbalance, building a feminized pipeline through projects such as DigiGirlz, which gives schoolgirls opportunities to learn about careers in technology.

Barnard’s life experience, she says, was formative and invaluable: “If you grew up in my skin – and in a skirt – you’ve seen a lot in the world, right?” Yet, at least in those early years, many organizations failed to see the value women could bring. “In my younger days, I used to sit in rooms, and I would make comments,” says Barnard. “And because these rooms were typically male dominated, people would listen – and then just move on from the conversation as if nothing had been said.”

Meetings were often challenging, she says: “I had so much to learn – I had early exposure into some of those executive rooms.” She recalls having just been promoted. “We had a regular 7.30am meeting. You can imagine how stressful it was to be seated by 7.30am as a single mother who had to do a school drop off!”

Voices unheard

Women’s voices are still not heard as easily or clearly as they should be. “Often meeting rooms are not trained to listen to women’s voices,” Barnard points out. “It’s because our tone is very different. Our tone is sometimes softer.” The consequences of this lack of female-fluency are serious. “When you come to these rooms, you don’t think, ‘I’m accepted as I am’; you often think, ‘I need to change’. ‘I need to change for acceptance.’ ‘I need to change to fit in.’

“But you know what happens when you fit in? You become a lesser version of who you are. You no longer operate with your exceptionalism and your uniqueness. In fact, some say that even your level of intelligence drops because you are overconsumed with trying to be ‘one of them’. This is what happens to many women, in many meetings, in many boardrooms.”

Should organizations be realigned to value more typically feminine qualities, rather than placing a premium on traits that are traditionally considered masculine?

“The answer is ‘yes’, but I would advance the conversation,” she says. “Because when you narrow it down to masculine versus feminine, it sounds incredibly polarizing. I want to talk more about inclusivity. The moment you become inclusive, you realize that everybody needs the right conditions for them to ‘show up’. And those conditions could be for women, or those conditions could be for black people.”

Organizations are missing the huge contributions that many of their people make, Barnard warns. “There are some people who show up with a whole lot of energy, and then you get people who are seen as quiet executors. And often when you look at it on the surface, the first kind of person could be perceived as amazing, and the other? Well, we forget to measure what their outcomes were,” she says.

“And often what you find – and these are broad generalizations – is that women are quiet executors. So, you could place a male-female lens on it. But it is really about throwing a wider lens on how different humans are – and thus how organizations need to become more inclusive in their cultures.”

Too often, the active inclusivity, for which Barnard is a standard-bearer, becomes muddled with numerical diversity – that simply having a breadth of views and experiences within the same office is sufficient. But are fresh ideas and diverse knowledge worth much if nobody hears them?

“I walk into meetings – and this still happens to women today – and ask whether anyone has a contribution to make,” says Barnard. “Trust me, more often not, it’s not a woman that makes that contribution. The ice often gets broken by a man. Men sometimes dominate the conversation because they trust their natural intelligence. Yet we must know that we are the intellectual equivalent of our male counterparts. And because I know it, I draw women out.

“I say, ‘tell me, what do you think?’ You need to invite them because they always think something, and sometimes their thoughts are invaluable. But there is still that hesitation of entering a meeting room and being the first one to comment, make a recommendation, or even disagree. It’s still a journey that women are walking.”

Plan for progress

Barnard has worked with Duke Corporate Education to design a women-only course that helps female employees themselves become the agents of change: catalysts for amplifying feminine voices and views in the workplace – and making them heard.

Does she think that women tend to lean into their natural character – bring their whole selves to work – or the opposite? “I think we’ve made a lot of progress compared to the generation before,” she says. “But I still find women tend to lean out of their natural strengths rather than lean into them.”

Core to her worldview, and the focus of the Duke CE programme, is Barnard’s observation that many women subconsciously consider compassion and courage as opposites and trade one off against the other. The secret to great leadership, Barnard believes, is to synthesize compassion and courage – to blend acts of fearlessness and acts of care.

Perversely, perhaps, compassion, rather than courage, is more often the first casualty of employees’ misguided attempts to counterbalance the two qualities. “I’ve seen women go, ‘I’m just dumping compassion, I’m now going to go just for boldness and fearlessness and courage,’” says Barnard. “And then they become too hard. Because then it doesn’t become humanly possible to properly manage people and be that amazing leader.”

Yet the reverse is equally as damaging: “If you pivot too much into compassion, it’s too soft for what you need to accomplish,” says Barnard. “There are always KPIs you need to hit. But if you can create an amazing blend of the two and oscillate between them at the right moments, you then find your balance. You create a people culture, but a people culture where you can be courageous enough to say, ‘I’m going to ask for my next promotion’, or tell one of your team, ‘I think you can step up your performance.’ But you can also be compassionate and say, ‘I get it, I suggest you take some time off.’ You must balance them because it’s never one or the other. It is always about combining the two. And I want women to understand that the two can, and should, coexist. It is their coexistence that makes women great leaders.”

Fusion leadership

This fusion – courage and compassion; hard and soft; dynamic and collaborative – is, says Barnard, the epitome of successful leadership. “What is the point about leadership?” she says. “The point is to be effective! People want to work for a strong leader. You can be nice to people, and they may like you, but they may not think you strong. People want to be led by leaders who are kind, strong leaders that can take them on a journey, show them a bold vision, offer ambition. Then they feel, ‘whoa, I feel I can join this person on this impossible task.’ But people want to see both sides. And if you don’t handle both, you can create a fearful organization where people are afraid – or you can be too soft in a culture where people don’t grow, develop, and create a standard of excellence.”

When you balance the two, you create what effective leadership looks like, says Barnard. “People want to win when they come to work. People want to work for amazing cultures for successful organizations. They want to accomplish great things. We like each other, we are inclusive, we have lovely meetings, we hear all points of view, but by the time we are done, what have we accomplished? What impact have we made? What does our business objective look like? We must always operate within a context of us having been successful together.”

Barnard’s relentless focus on the talent pipeline promises to deliver the compassionate courage – the courageous compassion – that will produce success in a challenging epoch. Does she think the world has reached a ‘feminine moment’, where traditionally female qualities gain the business-value they deserve? “There’s not been a better time for women to lead,” she says. “We now know from many surveys that in this new hybrid world of work, employees are asking for new things. The ‘Great Resignation’, the quiet quitting; people are saying, ‘we have discovered something new, I want something very different from work.’ What we have to offer as women has become quite invaluable, because a lot of organizations are pivoting towards empathetic leadership, leadership that understands people, leadership that puts people first, because this is absolutely what people need right now.” How widespread is that shift? “There is a greater understanding that what women bring is not inferior, it is just different,” she says. “Previously, because it was so different, it was seen as inferior.”

She worries, nevertheless, about a muddy, still-masculinized middle. Women are catapulted into the C-suite, and to the entry-level of organizations, but middle management remains dominated by men. “The top is female, the bottom is female, but what is happening in between?” she asks. “We need to bring more women into the room. And for those of us who are already in the room, it’s no longer about us. It’s about how we bring more women in to ensure that they are seated at the table. In South Africa, we’ve made great progress, but it is not perfect. It’s not over yet.”

Feminine future

She hopes her legacy will be self-sustaining, that the progress she has spearheaded in tech will multiply and proliferate. “So not just the women, but also the men understand the value that women bring to the table,” she says. “And for women to understand that they must continue to build and mentor and sponsor other women. And for men to understand how they must be allies in the conversation.”

Barnard climbed to the top despite immense disadvantage. Now at the top, she wakes every day thinking how best to maximize the huge influence her position confers. Bringing in others is key to a female-fluent future. “I’m Microsoft’s ambassador in South Africa,” she says. “I have great power sitting in this chair. So, what am I going to do with it? I need people that can create the snowball effect of power to make a difference.”

Ben Walker is editor-at-large of Dialogue.