Giving your people a sense of meaning is the key to success

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”https://issuu.com/revistabibliodiversidad/docs/dialogue_q4_2016_print_proof__cropp/36″ ]READ THE FULL GRAPHIC VERSION[/button]

The re-humanization of leadership has become one of the most pressing issues of our times. Two of our biggest clients, a leading pharmaceutical company and a successful global bank, have both been on a journey of over two years in doing precisely this, with very tangible rewards. Re-humanizing leadership is crucial for the 21st-century enterprise. What are the steps that will take us there?

What went wrong?

Human beings are meaning makers. The higher emotions of purpose, empathy, and shared meaning are critical as they build the foundations for sustainability. But with strategy becoming the proverbial one-eyed king in the country of quantifiable information, we spent much of the 20th century assuming that measurement holds the secret to mastery. We set up countless cottage industries inside our companies, devoted to the sole task of generating information and converting everything into smart decks, spreadsheets, graphs, and statistics. These are useful tools – as long as they don’t commandeer the central position in the complex system of meaning. But, sadly, that is precisely what happened.

Management became the science of finding the most efficient ways to maximize production by designing organizations as assemblages of clear, interlocking parts of functions, departments, and processes, managed by lines of command and control. ‘Re-engineering the corporation’ was about precisely this. The complicated financial instruments at the core of the credit crisis of 2008 were computer models to reconstitute bad loans. The models were wrong. But because they were quantified and looked smart, we assumed they were right. Purpose or intention had no place in the models. But greed and self-interest did.

To re-humanize leadership, we will have to overcome an Industrial Age worldview that taught us to define ourselves and our organizations as closed and fragmented black boxes.

This approach did seem to work as long as the world was assumed to be linear and a closed system. So strategy became the Holy Grail, and the harbinger of success. And yes, every once in a while we would pay lip service to our values, except those were not values at all but, at best, a list of aspirational statements that were unmoored from reality. At worst they were simply feel-good lines. Purpose had little or no value in a worldview that was defined by input and output. Our contention is that purpose will have to be the core leadership resource in the 21st century.

And as the business environment becomes increasingly complex and ambiguous, there is an even greater need to humanize leadership, imbuing it with deeper meaning and purpose. Yet so many organizations continue to position leadership as an instrument for maximizing efficiency or output, so much so that we have come to accept that as the norm. Yet volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (Vuca) makes this approach even more untenable.

The Vuca challenge

As the defining acronym for the 21st century, Vuca conjures up an unmanageable world in which disruption is the new normal and leaders had better adapt or perish. The fact is, globalization, convergent technologies, and a new millennial mindset of transparency and collaboration are colluding to obliterate the illusion of a predictable future. All along we had assumed we could navigate the future using the trusted recipe of information, capability, and strategy. In a recent survey by Duke Corporate Education, chief executives declared complexity their number

one challenge.

But complexity is neither the problem nor a new phenomenon.

Our earth’s life-support systems are highly complex – which explains their resilience for millennia. It is suddenly a threat only because we largely ignored it in the 20th century. We conveniently assumed that the world was neat and linear – and what got measured got managed.

The 21st century is challenging our belief in linearity. From global warming to global pricing policies, the linear walls that delineated competitors, governments, regulators, and technologies into understandable boxes, are crumbling in front of our eyes. Social media allows customers to talk to each other, access the same information, and influence public opinion with a point of view. The customer is no longer the passive recipient. We have to come up with an entirely new way of leading in the 21st century.

What gets in our way?

The organization trap

The biggest problem we have is that most of our organizations are simply not equipped to deal with this new reality. We built them on the assumption of a linear world; so we built neat-looking boxes of departments, functions, hierarchies and reporting lines. Now we demand agility, adaptability, and innovation from our employees, but we still reward them for status, obedience, and conformity.

The cognitive trap

Our brains are simply not adapted for complexity. Nature has prepared us for immediate danger and reacting instantly, but not for deciphering the weak signals of complex problems. Our brains lack the neural wiring to understand them. Ambiguity appears as a threat, triggering an instant reaction, which is inherently biased. That is why we would rather defend an established belief or strategy and ignore evidence to the contrary, than ask if we are doing the right thing.

The power trap

Our 20th-century hierarchical organizations replicated social status, which was achieved through the control of information and resources. But what now as the hierarchy itself comes under challenge? Recent research in neurology also demonstrates how those who ‘feel powerful’ through social status have a lower ability to feel empathy. The 20th-century organization engaged reward mechanisms in our brains to derive power from status; how willing are we to give that up?

Wrong mindset

Together, the three traps generate a reactive mindset, which propels us to act from worn emotional states and learned scripts without thinking. This mindset is redundant when addressing complex problems, and yet we see managers repeatedly falling into this trap.

Even the brain’s logic system is fallible. Much slower than the reactive mindset, the logical mindset is prone to cognitive overload and depletion, and when that happens, it simply hands back control to the reactive. The rapid and exponential growth of information is a serious threat to our capacity for attention, creating attention-deficit: we notice it in so many senior managers who are emotionally exhausted. Only a mindful mindset that resonates with purpose can overcome the limitations of these two mindsets.

Doing the right thing

In September 1982, several people died in Chicago from taking extra-strength Tylenol, which had been deliberately contaminated with cyanide by a still-unknown perpetrator. The manufacturers, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), withdrew every product from every shelf in the US and stopped production. The contamination did not happen in a company plant but J&J took complete responsibility for it. The company’s chief executive, James Burke, was asked later how he coped with the difficult situation of withdrawing products knowing that the share price would plummet right away. His reply was simple: “It was the right thing to do.”

The right action, the defining characteristic of good leadership emerges out of purpose, which asks the question, “Why do we exist uniquely in this world?” Leaders who operate effectively in a Vuca world are merchants of meaning, fluent in navigating complexity.

The head of technical support in our client bank spoke of the distress that would get channelled to the technical support staff when things did not work. He had a large organization with attrition problems, which was costing him a lot of money. But he knew that his function was doing the organization a huge service. Then, one day at a team meeting, he spoke about his four-year-old son, who was scared of the dark – and how if he left the door open a little bit, the light from the hallway would give comfort to the boy. The light became a metaphor for the purpose of the technical support function: “They’re scared and they’re nervous. So we’re providing them with that level of comfort. That’s why we’re here. Not to fix their technical problems.”

His staff turnover reduced dramatically. He had enabled his team to discover their meaning to the business, through a simple, humanizing process.

Leaders like this understand complexity. They know that it plays out in unpredictable and differentiated ways, but it is held together by principles of integration. These principles are usually obscure because it requires a higher cognitive level to see them. Rather than waste energy and resources in trying to control the differentiation, they focus their attention on stepping back and discovering the integrating principle.

Excavating and inquiring into purpose

As the very reason for an organization’s existence, purpose defines the ability to sustain its relationship with the world, allowing the organization to flourish over time. But most of our organizations either lack an innate sense of purpose or have forgotten it, and so it needs excavating.

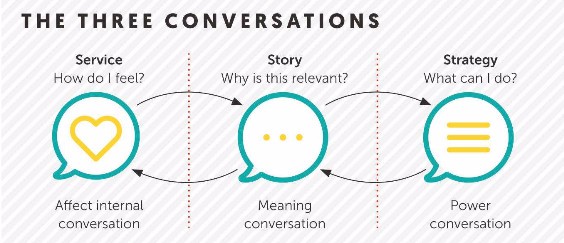

Leaders need to gather narratives, artifacts, perspectives, and ideas that reveal ‘latent purpose’. This is an oblique approach of listening in to what people are thinking and feeling – rather than asking them to define the purpose, which is a mistake that many leaders make. Only then can leaders start building the narrative that will eventually morph into organizational purpose. It begins by paying attention to what people say when they are asked the question, “Why are we here?” and about examining what they connect to, thereby discovering the artifacts that come out of those conversations. There are two conversations at this stage, the first one being the ‘affect’ conversation (see Figure 1). This one inquires into the feeling that the organization evokes in its people. We refer to this conversation as ‘service’: the notion here is that the call to serve is the highest ‘affect’ that people can feel. The second one is the ‘meaning’ conversation, which elicits the story of the organization and its relevance. This conversation is about the ‘story’.

Only after a thorough examination of affect and meaning can leaders turn to the third ‘power’ conversation, which is about finding the answer to how the sense of purpose can be applied. This is the stage where the conversations get strategic, helping everyone develop a clear line of sight with purpose, and understanding what they need to do.

Institutionalizing purpose

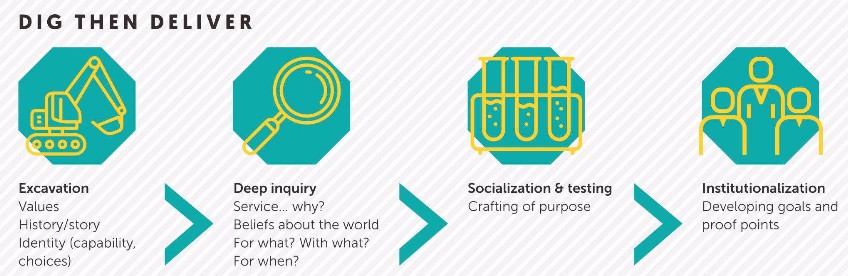

Both our clients are in the process of institutionalizing their respective purpose and it is beginning to percolate into the more tangible level of goals and strategy. Having gone through the stages of excavation and deep inquiry (see Figure 2), they have socialized it in multiple settings, and crafted their purpose. A new humanizing mindset is emerging.

In a complex landscape, where the exponential increase of information is making it impossible to know what is around the corner, purpose provides the integrating principle. It allows leaders to have different conversations with their people, using a mindful mindset that is capable of balancing the frenetic pull of short-term business demands with the larger and longer-term perspective of the ecosystem. The re-humanizing of leadership dampens the reactive mindset of bias and biology, and limits the overwhelming of the logical mindset.

The 21st century presents a crucial juncture where leaders must actively shape the evolution of their organizations through the re-humanization of leadership.

— Sudhanshu Palsule is a leading thinker in the fields of leading in complexity and transformative leadership, and an award-winning educator and author

— Michael Chavez is chief executive of Duke Corporate Education