We need quick solutions to the consequences of wealth disparity, writes Blair Sheppard

There has been much recent discussion about disparities in wealth. Disparity has been used as the explanation for much of the world’s ills – and is at the heart of a growing chorus of concern that the ruling elite is managing the world to line its pockets at a cost to others.

In theory, liberal democracy, pluralism and a well-governed market, as we understood them, were designed to mitigate this. Yet, the tenor of this chorus is often seen as a direct threat to our form of government, the role of business as we know it, and the institutions designed to make the world work. In fact, all institutions, at a global, national and local level, from multilateral global institutions, to multinational corporations, to our local police forces, are being questioned.

The strength and direction of this chorus has caused an interesting reaction in some circles. The reaction often begins with the refrain that there has always been disparity, which is what a meritocracy and market necessarily create; or it proposes we give everyone a basic living wage to appease those feeling most harmed.

I worry this discourse does not understand the basis of these disparities well enough, nor sees their interdependence with other forces in the world clearly enough to appreciate the structure of the disparities, how serious they are and what solutions could be proposed. I worry that we are looking through a 20th-century lens at a 21st-century problem.

I approach the topic in three distinct parts. First, I examine a few elements of the structure of the disparity that are important for us to understand. Second, I explore the factors that have significant interdependence with these disparities. And third, I suggest the beginnings of approaches to managing the issues.

The structure of inequality has changed

Inequality is a consequence of any economy and is arguably essential to motivate people to learn, work hard and take risks. As such, disparities between individuals are part of life and a positive force, providing it is fair. It creates the conditions for innovation and growth, which make society generally better off. The qualification of fairness, though, given the structure of the inequality we see today, is a real concern.

Something darker

Perhaps most important is that today’s inequality has two features that are particularly worrisome. The first is that the disparities are not just between individuals, but between locations. Some parts of cities are extremely poor and becoming more so, either because people in those sections of a city have no good means of transport, and the local work, educational and living conditions are much worse; or because particularly disadvantaged people have aggregated to that section of the city, often for identity-based reasons.

Some parts of countries are extremely poor and becoming more so, typically because their economy was based upon one or a few industries that were especially hard hit by globalization or automation, and they did not have the will or resources to adapt. Consider parts of the central US versus the coasts, or provinces such as Uttar Pradesh in contrast to Hyderabad in India.

Then there are some regions of the world that are extremely poor and becoming more so, for example, Latin Europe in contrast to other parts of the EU. Some parts of the world are extremely poor and at risk of not getting better; consider Central Africa.

The problem is that when whole parts of a city, country, region or the world are badly off, it becomes harder for people located in that area to escape disadvantage. Schools are worse, access to good jobs is generally worse, access to money is harder, subsistence costs are often higher and escape difficult.

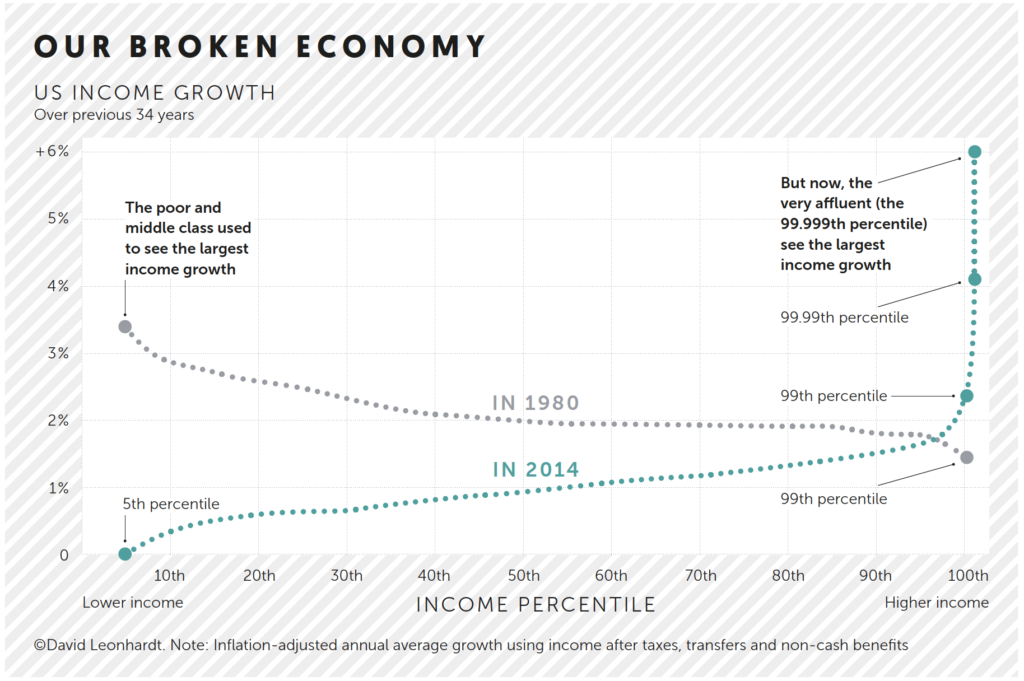

The second worrisome structural issue is illustrated by the graph on p23. On the X axis is the starting position in wealth, and the Y axis growth in wealth over time. The grey line represents the relation between those two variables over the 34 years leading up to 1980 (following the Second World War), and the red line the 34 years from then until 2014.

The differences are striking and suggest a significant shift in the structure of growth. Growth created benefit for people at all levels of wealth, especially the poor and lower-middle class, prior to 1980. Since then, growth has benefited the wealthy. One example of the result is the erosion of the middle class in the United States. While this graph represents the US only, the phenomenon is global. As an economy shifts from a manufacturing, labour-intensive economy to a knowledge-based and service-based economy, without some form of intervention, the tendency is for the wealthy to get wealthier and the middle class to erode. Think about how many people the growth of the car industry employed and the small businesses they supported, versus the growth of web-based IT giants today.

This structural change is even true for countries that have had a massive growth in the middle class in the last few years, because of tremendous economic growth. As they shift to a knowledge and services-based economy the same structural challenges will occur.

A permanent underclass

Why are these two phenomena dark? First, we risk creating a permanent underclass who live together increasingly worse off than their neighbours, countrymen or human beings. Or, if people are able to migrate, we hollow out whole sections of cities, regions or countries.

Greece lost nearly 1/20 of its entire population over the last ten years, and those who left were primarily the youngest and most employable. The country that gave much of the world its basis of culture and thought is being hollowed out by a dramatic regional disparity exacerbated by its relationship to the EU. Neither a permanent underclass nor ghost towns are attractive options for these regions.

Second, as the middle class erodes, the wealthy risk eating their tail: without a middle class there are no customers to buy the products and services the wealthy create. Clearly more very expensive luxury goods will be purchased, but wealthy people do not spend anywhere near the proportion of their wealth as the middle class. And, since wealthy people keep significantly more of their wealth in the form of capital, they pay significantly less tax proportionate to their wealth, even in progressive tax systems. Without taxes, governments fail to provide the safety net essential for the increasingly worse-off.

Interdependencies

Distressingly, there are also a couple of factors that act to multiply the consequences of disparity: age and disruption. The world is generally getting older, but in two very different ways. Around half of the world – Europe, Russia, Japan, Canada, the US, and increasingly China – have a significant number of their population reaching the normal age of retirement. The rest of the world contains a massive number of people about to enter the workforce. As an example, consider India, which needs to find between 8 and 14 million new jobs a year for the next 15 years. These two aspects of age multiply the problems of disparity in quite different ways.

For countries with massive disparities that are getting older, there is likely to be too much of a burden on those continuing to work, mixed with a significant number of people who are simply unable to support themselves in their older years. For those who are disadvantaged in countries that are significantly younger, the prospect of finding good work is very slim and the level of wealth in the country too little to provide sufficiently for those who cannot find work. Both circumstances are pretty miserable.

The other major interdependency is disruption, or the dramatic reconfiguration of business. Inevitably, the advantage in disruption accrues to regions and people with resources and education. Technologically based companies require fewer, more skilled workers, infrastructure and capital. Poor regions have none of those. Disruption also displaces workers. Those displaced first will be the ones who are just beginning to get out of disadvantaged circumstances, or those who have been at the same job for a long time.

The multiplier effect

Taken together, the two interdependencies are especially pernicious. Older countries are likely to have a set of people not yet at retirement age forced out of their jobs by disruption, but still deemed too old to retool or redeploy. Younger countries will not have similar access to the labour arbitrage that gave Japan, Korea, China and India their start. All of these countries began by providing lower-cost labour to outsource lower-end manufacturing and services. With the advent of technology, emergent labour in lower-age countries with massive job-creation requirements will be competing with robots that never sleep, do not get sick and get smarter and cheaper everyday.

Where should we start?

These outcomes seem dire – and they are – unless we change the way we think about the problem. Outlined below are a few ideas on where to begin, but just that: each of the ideas will require a real partnership between the public and private sectors and civil society.

1 Focus on local economies

If a significant portion of the challenge of disparities in wealth concerns disparities across regions or locations, then focusing efforts on enhancing local economic activity is critical. From farm to table, to ensuring a percentage of all expenditures are local, to creating a local microcurrency, to local entrepreneurial initiatives – we need to find a wide array of ways to drive local economic activity and trade. A major portion of the focus of national governments should be to find ways to help local economies thrive. And every firm should look at all the towns in which they operate as their

local town.

2 Create conditions to facilitate many start-ups

Given that disruption will take jobs out, and it is essential for competitive survival for large firms to become increasingly efficient, the solution has to entail massive creation of new firms. In addition to creating work, it has the additional advantage of shifting more people from employee to owner, creating motivation to invest and grow. The key will be to adapt successful strategies to the starting conditions of an area. For example, it will not work to port the practices of Silicon Valley to start-ups in Uttar Pradesh. National policy, state policy and the behaviour of large organizations should support the creation and scaling of many new businesses, especially in the areas where that does not naturally occur.

3 Redefine the role of the wealthy

Given that sustained disparity of the kind described above eventually hurts those who are best off, and given that with enough disparity the risks are far greater than just lost business, it behooves the wealthy to engage the issue directly. This requires more than giving money in a traditional manner, because the present options are clearly not helping. It requires a more active and targeted effort. This could mean actively engaging in projects to enhance education, create new businesses, or develop a significant tourist trade.

4 Redefine charity

We also need to rethink how charity should function. First, because of great regional disparities, charity does not and cannot only start at home. Second, we must focus on things that really address the causes as well as the consequences of disparity as it exists today, not as it has historically. Finally, charity needs to engage actively in partnership with companies and the government to have proper impact.

5 Work to address disparities early in life and sustain through school

The fundamental way in which regional disparity and a dissolving middle class become worse is when the next generation is trapped by the circumstances of their parents. Equal opportunity has no meaning if a significant percentage of the population in a city, country or region is handicapped from the beginning.

6 Find ways to turn disadvantage into advantage

As an example, consider the challenges of disparities in India. The sheer speed, scope and scale of the challenge require completely new solutions. To address the problem in a traditional manner would require building 2,000 new universities over a ten-year period to meet the educational demands of the 8-14 million people seeking new jobs a year. This approach will not work, but the youth still need to be able to contribute. It demands a radically new, creative approach.

Each of these suggestions is difficult to implement and, while each is being tested in some way in parts of the world, we do not have long before the problems I describe become extreme. If anything needs to change most from today, it is the speed at which we address our problems. I am considered, by everyone I know, an unbridled optimist. It is this last concern that makes me less so every day. I trust humanity to find the right answer – I just worry whether it will come soon enough.