The pandemic has triggered a fundamental rethink of every aspect of work. The Human Capital Era is upon us

The Covid pandemic has triggered a Great Reset: a re-calibration of every aspect of our lives. Perhaps the most significant has been in the nature and act of work.

Necessity accelerated the pace of digital transformation by decades. Organizations and leaders reluctant to honour workers with adaptable hours and work-from-home flexibility suddenly had no choice but to trust their people to get their jobs done – and they did. Front-line and often underpaid workers across dozens of industries endured daily risks to deliver fundamental services and, in the process, discovered and demanded their true economic value. As schools moved to virtual classrooms and daycare options evaporated, parents wearily juggled concurrent roles of worker, teacher and caregiver. And at the same time, a flood of headlines laid bare the brutality of systemic racism in policing, healthcare, education and myriad social and private services, catalysing critical conversations and long-overdue action to promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

All of this unfolded in the context of a highly contagious and terrifyingly lethal virus that gutted jobs and restructured work. This interruption was real and painful to many workers. Yet now, in the third year of this global disruption, the Great Reset is giving workers new power and agency, not just in where and how they work, but most importantly why they work, ushering in what we describe as the Human Capital Era (see for example Heather McGowan’s article on Forbes.com, 11 May 2021).

In the Human Capital Era, workers are valued as an investment to be nurtured, rather than an expense to be managed. It is reshaping every aspect of the American workforce, and it demands we rethink everything from the demographic composition of the workforce, to how we measure the meaning and outcomes of work.

What’s changing? Simply, everything.

Who works?

Our current structures of work, especially knowledge work, were designed in an age when men with few caregiving responsibilities dominated the workforce. The workforce of that era really put the ‘white’ in white collar jobs. Women in the workforce were an anomaly, and mostly in subservient roles. People of colour filled the ranks of blue-collar service workers.

That social structure is no longer our reality. The 2020 US Census revealed a US population more racially and ethnically diverse than at any time in history. There is no racial majority in the 18 and younger cohort which is filling jobs today and for the future. Further, in the century from 1920-2020, human lifespans around the world effectively doubled – and with greater longevity comes longer working lives. The diverse workforce is here.

Yet the workplace has not fully caught up with changing education trends. Women now account for 60% of US college enrolment, and have been out-pacing men in degree achievement since the 1980s. Women in the US now hold 10 million more degrees than men. Too much of that talent is on the sidelines, for many reasons (chief among them the lack of caregiving infrastructure, which is crippling when you consider that a recent study found that combining working with parenting is equivalent to working 2.5 jobs).

Today, there is an emerging appreciation of credentials earned outside traditional college settings. Well-funded and successful programmes, such as Year Up, Guild Education, Tech Elevator, Upwardly Global and others are shifting the narrative around hiring requirements by partnering with companies to offer employees everything from just-in-time credentials to fully-free pathways, to university degrees.

Of all the changes we track, the fastest moving change is our understanding of gender and sexual identity. Once fixed and binary, gender is now fluid and sexual orientation is a spectrum. For example, 17% of Generation Z identify as LGBTQ+ (Ipsos, 2021), and of that group, 25% say they expect to change their gender identity in their lifetime (Irregular Labs, 2020). Interestingly, though, more than half of Generation Z and Millennials surveyed believe gender markers are irrelevant in work (Bigeye, 2021).

Business has been slow to leverage this diversity. McKinsey has been tracking workforce diversity since 2014, gathering data from more than 1,000 large companies across 15 countries. The research clearly shows that “the most diverse companies are now more likely than ever to outperform less diverse peers on profitability”, yet companies are making “slow progress” on building diverse and inclusive workforces. This is changing: indicators including the Fortune 500 Measure Up and the Edelman Trust Barometer point to investor sentiment that diversity is now an essential business driver.

Diversity, equity and inclusion are vital to re-establishing social mobility, providing greater investor returns, and tackling complex challenges from income inequality to climate change. They are at the very heart of the Human Capital Era.

What do we do at work?

What we do for work is changing too. Digital transformation is driving huge shifts in the work that needs to be done by humans and the skills and knowledge needed for it.

Yet we still prepare people for work by codifying and transferring predetermined skills and existing knowledge to new workers. That system will collapse under the requirement for continuous adaptation as technology-driven automation and augmentation chew up 50% or more of today’s common work tasks over the next few years, as the World Economic Forum and Gartner Group both predict. Indeed, the shelf life of technical skills is shortening so quickly that the skills gap will never close. Instead of learning (once) to work, we will work to learn (continuously).

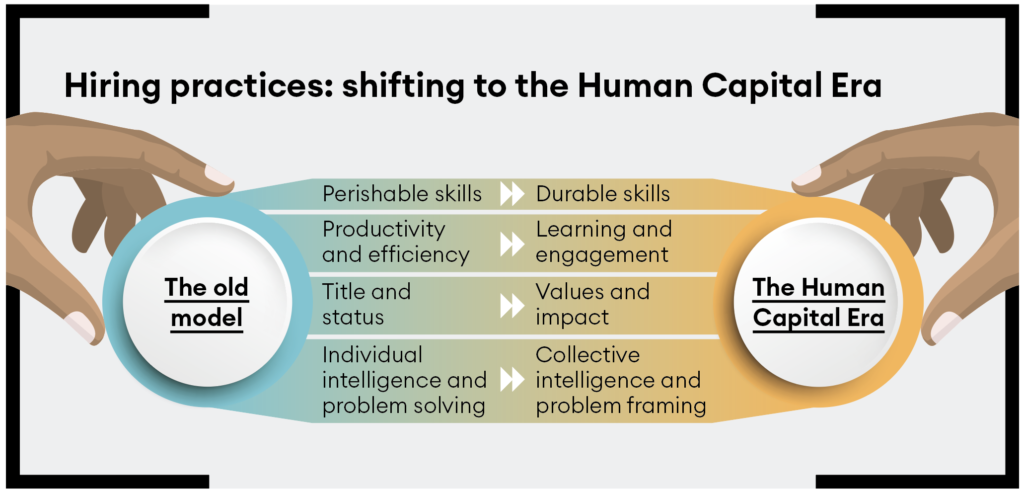

Employers must shift hiring practices to emphasize durable skills (collaboration, creativity, problem-solving and so on) over perishable ones (specific technical skills); refocus business practices to emphasize exploration (scalable learning) over exploitation (scalable efficiency); and reorganize to leverage collaborative tasks (complex problem solving) and collective intelligence over individual ones. Once technology consumes the routine and predictable, the work left for humans will be uncertain, complex and ambiguous – much like this pandemic.

These systematic changes are needed to create a diverse workforce of adaptable learners capable of doing the unknown work of the future.

Where do we work?

Prior to 2020, about 17% of working days in the US were taken remotely. When Covid hit, even the most reluctant business leaders were forced to embrace remote work.

The future of where we work is unsettled and may be for some time, given both a morphing virus and emboldened workers who have greater influence in where and how they engage with the corporate mothership. Many workers are unwilling to trade the safety and convenience of remote work for the benefits of in-person interactions.

Indeed, the argument that in-person interactions are essential building blocks of social capital and innovation remains unproven. Consider some provocative data. Of the top ten world populations, only two are countries; the rest are social media platforms. These virtual communities emerged in under a decade, well before Covid-19. Consider, too, that today about 25% of heterosexual couples and more than 70% of LGBTQ+ couples meet online. It is clear that we can and do build social capital and community virtually.

Those empowered workers are one factor in the decisions of nearly a quarter of corporations to downsize and reconfigure office space, according to KPMG’s 2021 Global CEO Outlook. Between those who have eliminated office space (21%) and those who plan to in the future (69%), it’s clear that chief executives see the future workplace as hybrid.

Longer term, emerging virtual reality and augmented reality technologies such as Facebook’s Horizon Workrooms, Google’s Project Starline and other experiments with the ‘metaverse’ are more than a gimmick; they have real potential to evolve into the next mode of work and collaboration. We have a lot to learn about how to leverage virtual workspaces, with ethical concerns still yet to be addressed on social media platforms – but we will do so while also re-thinking how, why and when to best use real-time and face-to-face interactions.

Place-flexible work environments and shifting work hours are the most immediately visible artifacts of the Great Reset. As virtually every employer struggles to define the new workplace and empowered workers set their own terms, we will no doubt see additional societal shifts. Human settlement patterns, for example, will shift as we centre our lives around community rather than workplace. That just might help repair a frayed social fabric too.

How do we measure work?

In 1926, Henry Ford found that accidents and errors peaked after the eighth hour of work. He capped the working day at eight hours. Productivity and engagement soared, and almost 100 years later, we still typically have an eight-hour working day – even though few of us are on the production line and fewer still do time-bound tasks.

In fact, recent studies bely the conventional wisdom that knowledge workers spending long office hours together are highly productive. Cognitive labour, research found, breaks down 4-6 hours into the working day – and sooner for highly creative work. Fewer hours may ultimately be more productive and beneficial. In Iceland, for example, recent experiments with a four-day work week have delivered dramatic improvements in worker well-being while delivering higher productivity and deeper engagement. In 2019, Microsoft experimented with a four-day work week in Japan and reaped huge gains in productivity, cost savings, and wellbeing, with less employee burnout.

Improvements in workers’ mental health and overall wellbeing correlate to improvements in performance for the entire organization. A mentally fit workforce delivers better ideas, better collaboration and better performance. Mental health – all health – benefits, then, are a smart investment in human capital, rather than a corporate expense. They are a very real strategic business driver.

No doubt, business will remain tethered to traditional measures of productivity, like revenue per employee, output per worker hour and so on, for some time; yet the knowledge economy demands new measures. A re-calculation of the enterprise value of companies on the S&P 500 found that in 1975, value was 17% intangible and 83% tangible; by 2020 it flipped to 90% intangible and 10% tangible (Ocean Tomo’s Intangible Asset Market Value study). What does this mean? In a world where tangible capital drives value – like that of Henry Ford’s production line – humans are a cost of production that must be contained. When human intellect is the primary source of value creation, humans are an asset of investment. The value of the human capital asset will be measured on two linked vectors: engagement and mobility. Engagement is the commitment the worker has to the organization’s goals and objectives. Mobility is the opportunity the organization provides the worker to learn and advance. They are critical to company value in the Human Capital Era.

Why work?

Once, we worked for survival. Then, we worked for identity and status. Now, more and more people are working to fulfil a greater purpose. Recent McKinsey research found that 50% of the workforce is looking to change occupations in the next year to better align with their purpose and values.

If we need our workforce to learn and adapt continuously – and we do – we need to help that workforce connect to their internal motivational drive, not rely on today’s external incentives and punishments. As workers shift to more purpose-centric employment, corporations face increasing pressure to align purpose with profit, and explore the interconnections and interdependencies of worker empowerment to create a truly human-centred workplace.

The Covid-19 pandemic, while tragic, forced long-overdue behaviour changes and reset mental models around where works takes place, who works and how they are supported, how work is measured, what we do for work and how our workforces are prepared for it. Perhaps most importantly, though, the trauma of the pandemic forced an examination of why we work. We stand at the threshold of a tremendous opportunity to rethink work to unleash more potential, engender deeper engagement, and deploy more of our society in improving the human condition, in no small part through re-establishing our lost social mobility.

The Human Capital Era is here. It’s up to us to make the most of this tremendous opportunity.