In an era of constant disruption, the ability to adjust course quickly is the difference between business failure and success

The only constant is change. The consulting firm founded by Clayton Christensen, Innosight, estimates that half of the companies in the S&P 500 will change every 12-14 years. Almost every day we read about a once-great company struggling to maintain its historical position. At the time of writing, the previously ubiquitous discount retailer Kmart has been reduced to only three stores in the United States. General Electric, which was the most valuable company in the US in the year 2000, was broken up into three pieces in 2021.

As leaders we must ‘see around corners’, as described in the latest book by Rita McGrath. But anticipating disruption in our markets is clearly not enough. We must also be able to quickly execute on the changes we decide are needed to move in new directions. Companies must assess how quickly they can activate any change.

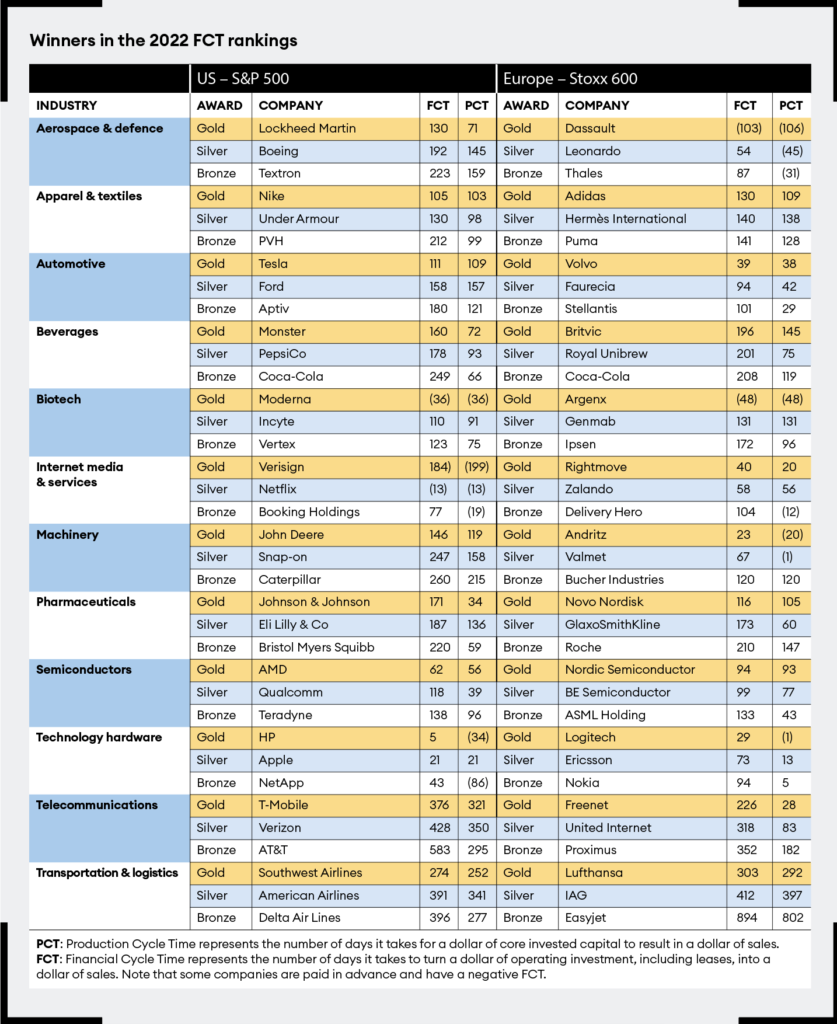

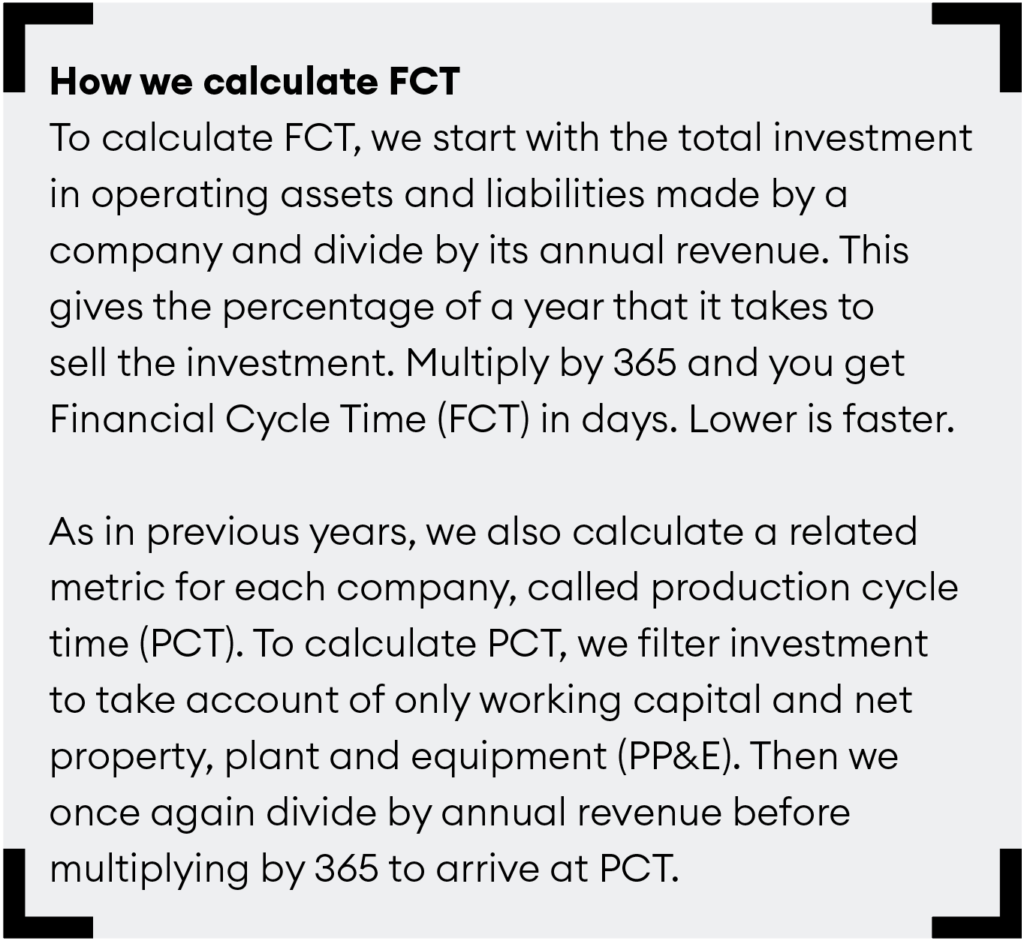

For the last five years, we have published rankings for financial cycle time (FCT) for some of the largest companies in the world. At its simplest, FCT measures how long it takes a company to turn a dollar of investment into a dollar in collected revenue. But what we’re really trying to measure is how fast a company can move.

Take the example of Southwest Airlines in the North American airline industry. In 2021, its FCT was 274 days, while the next closest competitor, American Airlines, was at 391 days, with Delta Air Lines at 396 days. It is clear from the data that Southwest Airlines is able to move much faster than its peers.

Another industry winner, in the telecoms sector, is T-Mobile. Their FCT was 376 days, with Verizon at 428 and AT&T at 583 days. T-Mobile has rolled out its 5G network more quickly than its peers and, of the three, can now can boast the fastest data speeds for the most customers.

As we created the metric for FCT, we started with a simple premise, aiming to answer a few key questions. How long does it take a company to make a decision? How long does it take to develop a product? How long does it take to manufacture its products? How long does it take to get those products to the market? How long does it take to get paid? Those questions get to the heart of how rapidly a business is able to move in today’s markets, and how nimbly it can respond to changes that require a strategic response.

Sources of disruption

Strategy is a series of simple questions: who, what, where, when and how? Consultants will adapt these questions of course, with different terms and sophisticated models – you can’t charge a company millions of dollars if you use such simple terms – but these are the questions that every strategy boils down to.

The three most important questions for managing disruption are why, what and how. ‘How’ companies – that is, companies whose thinking about their business models is based primarily on thinking about the how – are typically the first to be disrupted. ‘What’ companies can often face challenges too. But ‘why’ companies generally prove to be more enduring.

Leaders must deal with two questions. Are we defined only by the how and the what – or by why?

Think back to March 2020 when Covid-19 was spreading like wildfire around the world. Governments were putting in place drastic measures to close down social gathering-places. Among the first places to be shut down were movie theatres. The ‘how’ of watching a movie was therefore the first thing to be disrupted; you could no longer go to a cinema. What you wanted to do (watch a movie) had not changed, and you could still watch a movie in other ways, via services such as Disney Plus, Netflix, Hulu and so on.

But as people stayed home longer and longer, an interesting phenomenon started to emerge. What we wanted to do to – be entertained by movies – started to change. We started to look for other sources of entertainment. In the US, one of the fastest growing segments of video gaming other than a good, old fashioned bingo tour in 2020 was adults over the age of 45.

But regardless of the changes in the how and what of our consumption of entertainment, there was one constant: the why. People wanted to be entertained. As Simon Sinek has pointed out, the why is the most enduring. The lesson is this. If you are a how or a what company, you have nowhere to go when the market shifts. It is extraordinarily difficult for a company to change when their identity is tied up in those two questions.

The dangers of failing to change

In the early days of online video, the dominant movie rental company was Blockbuster. This was a true how and what company. We went into a store, rented a video and took it home. That business model really worked: it created tremendous value. But when the world shifted to streaming, the company was unable to change. Its identity was tied up in the how and the what.

Blockbuster failed to realize that customers would like different options for watching movies, and enjoy the convenience of streaming. It needed to adapt – but never did. In contrast, Netflix, the silver award winner in this year’s FCT rankings for internet media and services, has successfully pivoted twice: from video rental to online streaming, and again to content production. Netflix understands the why.

Another warning can be found in the history of Sears, once a great American success story and a dominant player in the retail industry for decades – including in home delivery. The Sears catalogue offered a vast range of products that could be mailed to your home years before Jeff Bezos started Amazon (our gold winner for FCT in ecommerce). But over the last 20 years, the retail world has seen a dramatic change, with online shopping becoming dominant. Despite having done home delivery for years, Sears was unable to adapt, and was ultimately crushed by the weight of its legacy stores.

If leaders are to avoid a fate like those of Blockbuster and Sears, they must deal with two questions. Are we defined only by the how and the what – or by why? And, if we are able to shift and stay relevant to why: how fast can our organization change course and implement change?

Financial cycle time can help measure the speed of an organization. It is a critical component of business success in a disrupted and constantly changing world.