Professional teachers beat neglected facilitators every school day of the week, write Pim Pollen and Ben Laker

Student-led projects and DIY learning strategies might have found new popularity in 21st century Education – but without professional, knowledgeable, engaged teachers, such strategies will see students (and schools) fail.

Take heart, then, in our latest research: teachers want more support, more knowledge and improved skills. They want to be ready for the 21st Century Education. They want to be the best they can be.

Pop quiz

Q: What is the number one indicator of student performance in reading and math?

A: Teacher quality

Most school governors and board members around the world have no link to education beyond their time spent as students. With no experience behind a teacher’s desk, they cannot be expected to intuit nor anticipate the challenges and opportunities of contemporary education. But the people who do – educators themselves – are rarely asked for their input at this level.

Almost 75,000 teachers and support staff from The Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Turkey, South Africa and Mozambique responded to our request for more information about their roles and challenges.

Asking questions

74,403 primary, secondary and tertiary level teachers and supportive staff from The Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Turkey, South-Africa and Mozambique completed the Professionality Scanner (Prof Scan) web-based questionnaire that asked them to rate and evaluate themselves. Consisting of ± 70 questions spanning 40 competencies, each derived from international research on education

Using self-assessments of the group’s knowledge-competencies, skills and ambitions, we have been able to put together a complete picture of how teachers see themselves and, importantly, how they would like to grow in the years to come.

The results are in

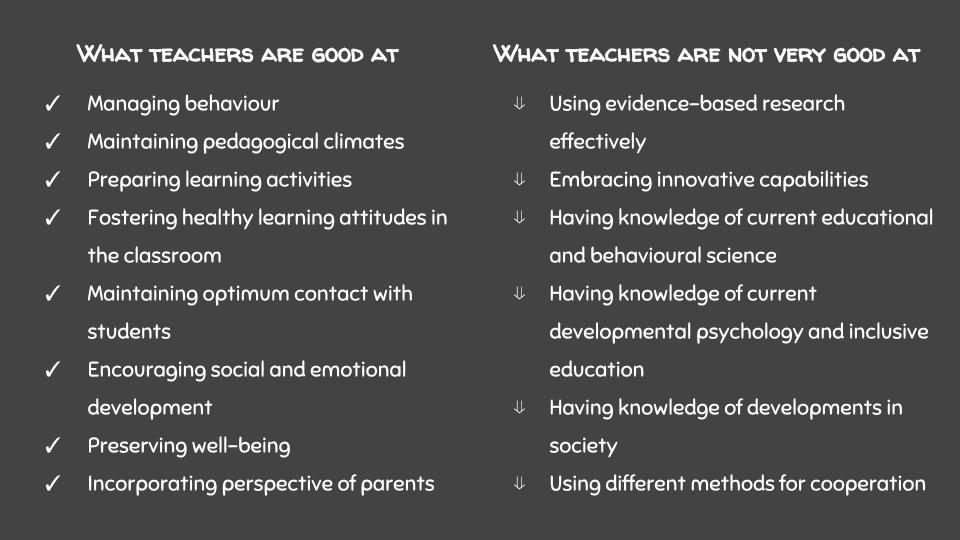

In general, teachers believe they are people-people, with a good grasp of interpersonal and organizational competencies. They also pride themselves on being resourceful and capable of working together with the environment and parents.

Where teachers see themselves failing, however, is in whether or not they have enough knowledge of a subject, evidence-based educational and behaviour sciences, and developments in society.

Without speculating on the cause of this (for teachers) confidence-busting and (for parents and students) inconvenient truth, the reality that our teachers do not believe they have enough knowledge is worrying, to say the least.

And, facing bursting classrooms, the future’s many distractions and ever-deepening budget cuts, now is the time for leadership to act.

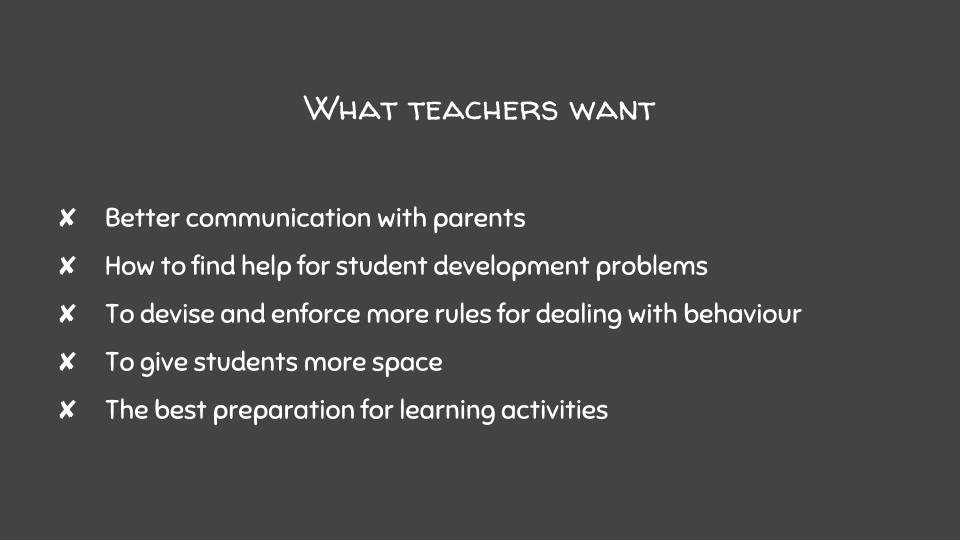

What teachers want to learn

With analyses of the opinions and insights of teachers actively serving students every day, leadership has the opportunity to determine starting points and quantifiable aims for professional development.

Allowing teachers to self-report professional development ambitions also provides valuable insight into how effective – or not – a strategy really is. For example, we asked the sample to rate their progress towards annual goals. Such insights could prove especially valuable as showing results of teacher professional development in student test scores could take time.

The long and winding road

Join the learning community

Sharing teacher insights can also foster arguably the most effective learning strategy around: the professional learning community (PLC). The professional development equivalent of high performing teams in organizations, PLCs are groups of teachers who commit to the achievement of better learning outcomes for pupils. In perfect PLCs, members undertake dedicated research and share learnings with each other, shifting their focus from didactic, one-way transfers of information to continuous learning as a team. Profoundly affecting the practices of schooling, PLCs are primarily for the benefit of students, and act as self-sustaining, sharing communities in which all teachers embrace continuous improvement and learning.

Characteristics of the perfect PLC

Strongly oriented towards action and results

Culture of collaboration

Key shared goals based on qualitative data

Shared leadership

Explorative student interventions

Hire an Architect

With the introduction of PLCs and other professional development approaches, teachers – and entire schools – may quickly find themselves part of one tier, as educated educators, or the other, neglected facilitators. Connecting two tiers in the real-world means asking architects to design a bridge. The same approach applies in the world of teacher professional development.

Mentioned first by Hill, Mellon, Laker and Goddard last year in Harvard Business Review and Dialogue, Architects are the type of leaders who thrive when it comes to long-term continuous improvement. Quietly redesigning their schools and systems to create the right environment for teachers, students and community, Architects are the people who give up their spot on a life raft and find a sustainable solution to the problem at hand.

Architects, therefore, with their quiet, sustainable transformation strategies and determination to install a positive movement and legacy, are arguably the only leaders who can successfully foster professional development across the school and wider system in the long term.

It is a style school leadership must quickly adapt or attain if students’ education is to shine.

Small steps for teachers and a giant leap for Learning

Many have argued the lack of professionalism and increase in scale within education combine to see the role of ‘teacher’ impoverished and simplified. Were the smaller steps discussed here successfully adopted into the education system, teachers and school leadership may wish to co-operate at a higher level: Together, they could take one giant leap towards formal empowerment, such as allowing teachers ownership of the curriculum and related professionalization.

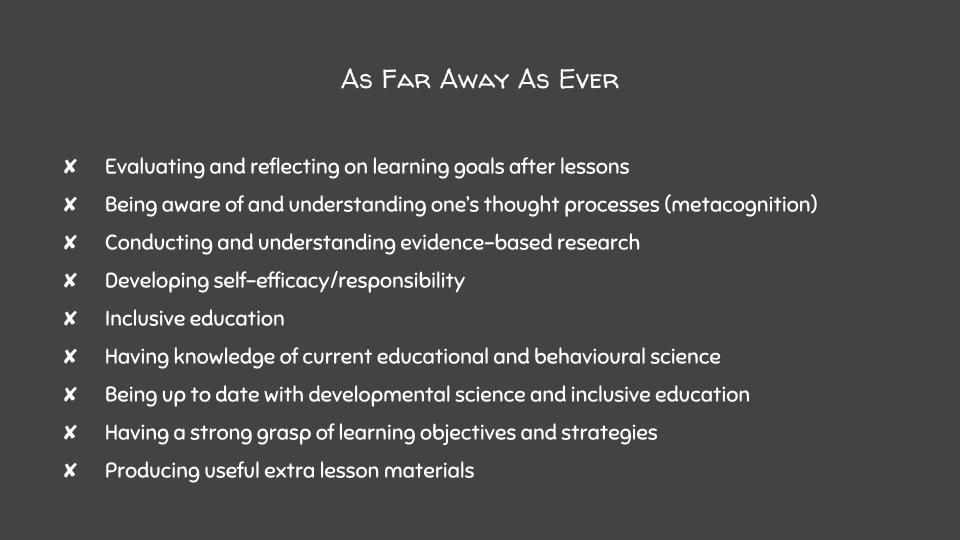

Evolving curricula to incorporate the professional opinions and experience of teachers could also address three major capabilities that teachers are determined to gain, yet are significantly far from obtaining.

The case for curriculum ownership:

- Being able to put learning goals into context for students will greatly affect understanding and impact of education

- Greater responsibility for teachers could ignite passion for a subject and more energy in the classroom

But the most valuable information teachers can provide to curriculum boards can only be divined by asking them the right questions – so we implore you to make time to ask the school community where they are right now, and where they need to be.

High Performing Schools: You may begin

Obtaining the best from students first requires schools to attain the best from their teachers. Accelerating professional development is going to require the gaining and growing of professional knowledge and classroom skills to improve Learning.

The most effective strategies will involve designing professional development based on the views and capabilities of teachers themselves, and allowing educators to grow both formally and informally in new, innovative ways. This might require Architect leaders to come to the fore, and will certainly need long-term sustainable transformation school-wide, at all levels of community and leadership – to the benefit of teachers, students and schools for years to come.

— Pim Pollen is senior advisor of the Academica Business College with a focus on transforming schools into high performing schools. Dr Ben Laker is a leadership professor at Henley Business School, advisor to Fortune Global 500 firms and Academy Awards commentator

— Discover the building blocks to better schools and join us in Amsterdam at Making Shift Happen, November 28, 2018

Further reading

Hill, A., Mellon, L., Laker, B., & Goddard, J. (2016). The one type of leader who can turn around a failing school. Harvard Business Review, 20. Hill, A., Mellon, L., Laker, B., & Goddard, J. (2017). How the best school leaders create enduring change. Harvard Business Review.

Marzano, R. J., Waters, T., & McNulty, B. A. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. ASCD. Darling-Hammond, L. (2000) Teacher Quality and Student Achievement: A Review of State Policy Evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8 (1).

W. L. and Rivers, J. C. (1996). Cumulative and Residual Effects of Teachers on Future Student Academic Achievement. Research Progress Report, University of Tennessee, USA.

William, D. (2016). Leadership for Teacher Learning. Learning Science International Evers J. and Kneyber R. (2016). Flip the System. Routledge

Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R.E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work. Educational Psychologist 41(2), 75-86