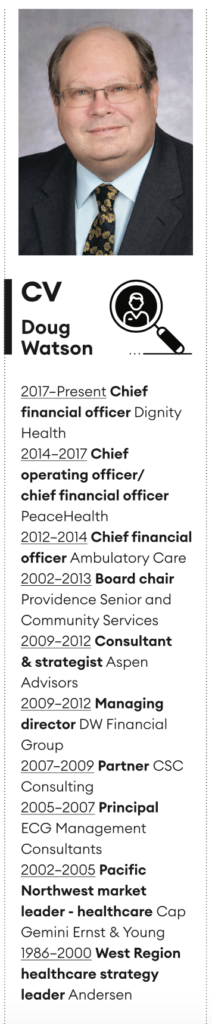

Dignity Health chief financial officer Doug Watson is on the frontline in America’s fight against the virus

It’s 8.30am mountain time at Ground Zero. Doug Watson meets me in the modern way, over Zoom, from his kitchen in Phoenix, Arizona. It’s early summer and the intense heat of the desert hasn’t done anything to prevent the virus accelerating across the Grand Canyon State. Arizona is staring into the abyss. How is he bearing up? “Good. I’m as good as I can be given what we are dealing with here,” Watson says.

Watson joined Dignity Health as its chief financial officer more than three years ago. Dignity Health is part of CommonSpirit, into which it merged in 2019. The merged organization is the largest not-for-profit healthcare provider in the US. Watson has enjoyed a distinguished career in financial management: he’s been a strategist and a consultant; he’s worked as an auditor in the Big Six. Becker’s Hospital Review named him one of the leading chief financial officers in the industry.

CommonSpirit trades under the brand name Dignity Health in Arizona, Nevada and California. Watson was attracted to Dignity Health, he says, by “a fantastic group of people – in particular our leader in the Arizona market, Linda Hunt – an amazing person” and its leadership: “Lloyd Dean [the chief executive] and others are just really focused on what we are trying to accomplish and are really helpful in making the organization something we can be proud to be part of, but also proud of the difference we are making in the community.”

Watson was intrigued, he says, by the complex healthcare environment in Phoenix: it has Barrow, one of the world’s leading neuroscience institutes, and the Norton Thoracic Institute. Dignity has a programme for “folks who are unable to pay – that’s one of the cornerstones of our environment – we take care of everybody, whether they can pay or not”. It runs its own $4.5 billion health plan that focuses on care for Medicaid. It has a large fleet of ambulances. It commands a network of emergency rooms across the Valley of the Sun.

It works creatively to match available state resources to services. It has launched a housing programme to offer better housing to people with mental health problems who previously were “afraid for their safety, or didn’t have the ability to get a good night’s sleep”. By intervening early in the housing sector, Dignity Health has saved on costs and improved health outcomes simultaneously. It’s an all-encompassing, holistic setup: “We have services where people come from around the world to see us, right down to the basic straightforward care for the most vulnerable in our community.”

“Keeps me entertained all of the time,” says Watson, phlegmatically. Even without the virus, there would be a lot going on.

Situational leadership

But there is a virus. And it’s hitting Arizona hard. When we speak, the state’s lockdown has been eased – and cases are shooting up again. Leading the finances of a major healthcare player amid a medical explosion seems almost too big to comprehend. “The first thing you recognize is that no one person is going to be able to do this by themselves, so I’m just one person trying to work my way through this,” says Watson.

He recalls a training course in a former role where senior managers were put in an alien environment and were asked to make sense of it. “In our case it was one of those TV kitchens,” says Watson. “We got a bag of ingredients and had to figure out how to make dinner.” Did they feast or starve? “You know what you find in these situations is that situational leadership emerges. The organizational chart might say that this person is at the top and that this other person is right underneath them but, in that sort of environment, you have the people who know what they are doing, and those with the right skills and expertise rise to the top. And hopefully that’s what you see in healthcare. Our chief medical officer and chief nursing officer have done a fantastic job of stepping into leadership because this is a clinical problem. First of all, we have to work out how we are going to restructure ourselves and do things that we have never had to do before. How do we test everybody coming into the hospital? How do we test everybody coming into a clinic? How do we redesign an emergency room waiting room so there is social distancing?”

Watson is well aware how fast the world of healthcare has changed. “You know in the old days, you’d be in a crowded waiting room full of people and you waited to be called back. We’d call you back, we’d do some triaging, you’d have some tests and you’d go back in the waiting room for a while, and then we’d bring you back again. Well, we can’t put you in the waiting room pool today because it’s unsafe. We have to find a way to socially distance those patients so they are not sitting in a chair next to a person who is sick and who may or may not have Covid. There are logistical challenges, and there are clinical challenges: we are learning more every day. But I’d say most clinicians think there’s still more that we don’t know than we do know.”

Shutdown

Beyond all that, Watson faced the sheer challenge of rescaling. Before the economy reopened, Dignity Health was eerily quiet. Each winter, Arizona’s sun-drenched climate attracts ‘snowbirds’ from the cooler parts of the US, swelling Phoenix’s population as the northern cities shudder in the frost. In the summer, the population falls back as people try to escape the fierce heat.

“November, December, January, February and into March, we are usually extremely busy,” says Watson. “We had that period where we were pretty much as full as we could be. Then, as Covid got going and the shutdowns happened – and, as mandated by the state, we were not doing any non-emergency procedures – our volumes dropped dramatically.”

Watson suddenly had an income problem: “We were in a situation of, ‘How do we preserve our staff? How do we make sure people can make a living when we don’t have work for them to do?’” He worked tirelessly with the systems team to work out a way to flex, even examining adjustments to salaries at the senior level so the workforce would be preserved and protected.

Then the lockdown ended, and the juggernaut shunted in a split second from reverse to overdrive. “There was a dramatic increase in cases in the Arizona market,” recalls Watson. “We’ve been really challenged by how the number of hospitalizations has increased day-over-day and week-over-week. And it then becomes very difficult to go from where we were – really scaled down – to creating surge capacity.” The state of Arizona required Dignity Health to consider scenarios in which it could accept patients at 125% and 150% of its licensed bed capacity. “We thought, ‘How do we do that, where do we get the beds from? How do we get 50% more patients in a busy hospital on the same footprint?’ That’s a very challenging thing to do in a way that is safe, and in a way where we can provide high-quality care to the patients. It went from one extreme to another.”

It was a critical situation. But Watson stepped up. He is a visionary first and an accountant second: when I refer to commerce in his market, he picks me up on it: “Well, we don’t think of it in terms of commerce,” he says, “but I do remind people that the more margin we are able to generate the more mission we are able to live out.”

Dignity Health procured beds on a rental basis to boost capacity. “From a financial standpoint you look at it and say, ‘I have got beds that I don’t need that I might need, how do I make sense out of that financially?’ Well, it’s hard. You can’t. But you do the right thing for the community and then figure it out.”

The common good

When we speak in early July, Watson warns that he “doesn’t know exactly what’s going to happen”. Arizona is in a perilous state. Yet I would back this great strategist and impassioned advocate of healthcare for all to find a way through. Has anything positive come from the chaos? “Leadership from our clinical leaders to step up and think, ‘What is the right thing to do and how should we try to do it?’” says Watson.

Healthcare is a competitive environment in the US. There is no single-payer system like that in Canada or the UK. Yet the crisis has triggered an outbreak of cooperation. “We have other health systems in the market, and on one level we are competitors,” Watson says. “But on other levels we need to collectively step up and do what needs to be done.” A surge line has been created whereby patients call one phone number that is operated jointly: “Those folks will figure out where’s the best place for that patient to go – both to match their need but also to level the load so we are not overloading any one hospital with an excess number of cases. If we’d not done something like this, whoever answered the phone first or was physically closer would get the case, and you’d have some hospitals overrun while other had capacity.”

This collective endeavour appeals to Watson’s strong drawn sense of community. “It’s unusual to see competitors put that aside and come together for the common good,” he says. “It’s rewarding to see that. Not only can they do it, they can do it well and in a way that really does put the patient first.”

Watson is a good man in a good place, at an incredibly demanding time. “That’s where our name CommonSpirit comes from – it’s a belief in the common good,” he says. “I say this, and I guess it’s a bit of a cliché, but it’s true: ‘We don’t practise medicine so we can make money. We make money so we can practise medicine.’”