Bring on the battle with the robots – empathy will win it for the humans, writes Professor Vlatka Hlupic

[button type=”large” color=”black” rounded=”1″ link=”http://issuu.com/revistabibliodiversidad/docs/pdf_book_q2_2016_mid_res/48″ ]READ THE FULL GRAPHIC VERSION[/button]

Many analyses of technological progress assume this is the dawning age of the robot, and that machines are on some sort of collision course with human communities. The theory runs that as artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated, it will replace us in many roles and leave millions of human beings at the margins. Those who try to halt this robotic march are told they ought to recognize it as inevitable and should keep abreast of the latest gadget or piece of code that will deliver the revolution.

The whole proposition is upside down. It is the technology prophets who are missing some of the most significant breakthroughs in science – specifically in the emerging discipline of social neuroscience.

It is often asserted that machines can be made that are more intelligent than humans. And you can set tests that appear to support this assertion; the most common being that a machine can beat a grandmaster at chess. But this experiment is typically rigged in favour of the machine: the task is computational, dealing within the known parameters of events, and the human is an individual.

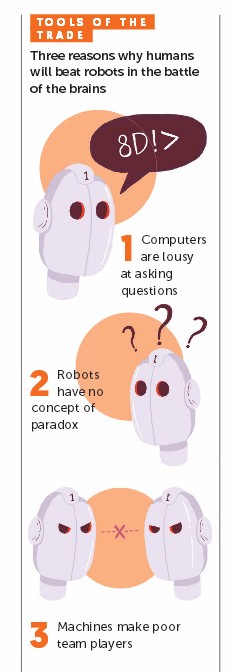

Yet where tasks are more ambiguous, or subject to unexpected events, and common sense or judgment is required, people are more effective than computers. Moreover, teams of people can be far more effective than an individual. The supreme irony is that it takes a highly gifted team of people, communicating and working effectively together, to have produced the artificial intelligence in the first place. Many breakthroughs, such as the electrical light, the programmable computer, the jet aircraft, are associated with a pioneer’s name – Thomas Edison, Alan Turing, Sir Frank Whittle – but these individuals headed multidisciplinary, highly engaged teams of people.

As management author Professor Julian Birkinshaw points out, computers are good at providing answers but hopeless at asking questions. For innovation and a nimble approach to strategy, the successful firms and teams ask the right questions.

Humans are also capable of grasping paradox. The evidence from the most effective organizations is counterintuitive, something that the Whole Foods funder John Mackey refers to as “the paradox of profit”. It turns out that aiming to maximize shareholder value doesn’t maximize shareholder value. This has been known for some years, but the learning is slow to percolate to a management population brought up on MBA notions of linearity.

Organizational dynamics

Breakthrough discoveries on organizational dynamics and performance are potentially some of the most valuable of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, but they are not so easily demonstrable as a shiny new aircraft or a tablet computer. We have learned that a highly effective team, or organization, is much more than the sum of its parts. It is also the case that a highly dysfunctional team is less than the sum of its parts – but this point merely underlines the importance of paying close attention to these dynamics. Neglecting this dimension, and focusing solely on technological advances, has thwarted progress in the past.

Some of the findings on social neuroscience, supported by decades of empirical evidence on the most effective organizations, show that collaborative efforts by human beings add up to more than the sum of individual intelligences; that there is a collective supra-intelligence, similar to an ant colony, when people are intelligently led and work effectively in teams. Much of my research in recent years has been devoted to understanding this powerful dynamic and devising means to realize it in the real world.

So a highly motivated, brilliant team isn’t just more capable at a cognitive level, it moves to a higher level of consciousness, often surprising itself at its capabilities, committed to continual learning and inventiveness. My own work supports the concept of levels of operation for an organization and a team, from level 1, characterized by apathy or destructive behaviour, through to level 5, where passionate people combine creatively and with inspiration (see infographic, below).

Questionnaire-based analysis shows that, where the level of operation moves up, so does organizational performance. There is a particularly significant shift from level 3, which is ordered and bureaucratic, to level 4, which is where highly engaged and inventive performance begins. At the neurological level of the individuals involved, it can be demonstrated that their brains and emotions are actively more fired up when so inspired; that the enthusiasm and passion are literally infectious from one person to another. This is science, not poetry. Or perhaps it is both.

An important feature of this high-performance culture is that financial returns improve, sometimes spectacularly. So it isn’t a choice between, on the one hand, a humane organization keen to develop its people’s potential and, on the other, a ruthless quest to maximize profits. You can do both, with the right leadership. Moving from level 3 to 4 is to move from ‘I’ to ‘we’. Moving from level 4 to 5 is to move from ‘we’ to ‘the greater good’. And it is at this point that profits start to become maximized, including returns for the ‘I’ – individuals. Th is paradox of profit is only now starting to become mainstream thinking.

Nurturing the human community

The theory about robots taking over might be more convincing had it not been apparently rejected by the very companies responsible for the so-called march of the machines. Some tech firms, for example, have a clear understanding of the complex dynamics of team behaviour, and place much attention on nurturing the human community as a means of fostering innovation and high performance. Google, for example, seeks to hire for the right culture, and build teams; it also deploys workforce analytics to gauge the effectiveness in these disciplines. At the Google X Laboratory, leaders actively seek to create a level 5 atmosphere of boundless passion, optimism, collaboration and inventiveness. They are encouraged to ‘shoot for the moon’, not tied to the annual budgets, arbitrary targets and rules of a level 3 operation.

Not all workplaces should resemble an experimental laboratory; for many enterprises there is a need for a more stable and reliable way of delivering an existing product or service to the desired standard. In this context, however, the health of the human community is just as important.

Ultimately, all profits are a by-product of mutual trust, which is an unchangeably human characteristic. Customers trust the company to enhance their quality of life at least as much as it says on the tin, or in the advert. The collapse of the share price in the car giant Volkswagen this year has come about because of a collapse in trust, after the firm was alleged to have been cheating statutory tests to determine the level of the more poisonous chemicals in exhaust fumes. While people are innocent till proven guilty, trust doesn’t wait on the court judgment. The consumer asks herself: Am I buying what I thought I was buying? If the company misled me on emissions levels, has it misled me on anything else?

Economy innovations such as Uber or Airbnb will only be sustained through customer trust. Technology is no more than a facilitator. So while the non-scientifically trained population does need to stay abreast of technological developments, it is at least as important that the geeks stay in touch with research on organizations and society.

The breakthrough findings on social neuroscience, and the nature of high-performing firms, ought to transform the terms of reference for discussions on implementing technology. Traditionally, the discussion is posed as: “If we maximize technological progress, is there a risk that people and communities get left out?”

We can now off er a radically more optimistic framing: “If we understand groups of people better and how to get the best out of them, we can innovate more effectively and get the best out of technology to help create a better society.” It’s an idea that no machine would have dreamt up.

Professor Vlatka Hlupic is a management consultant, executive coach, award-winning international thought leader and author of The Management Shift