Marketers need to learn to use reliable sources, robust science and persuasive stories to sell in the 21st century

It should be a principle of 21st-century communication: Thou shalt not lie to your customers. We would also need to add, Thou shalt not teach them falsehoods. They are commandments with particular relevance to the fast-growing field of science-based marketing and communications.

Policymakers, cosmetic brands, HR analytics teams and sports broadcasters all use scientific and data-led insights to co-opt audiences to their way of thinking. But whether it is being used to convince constituents to accept vaccines, sell pricey moisturizers, influence workforce planning or encourage betting, scientific storytelling should be unassailable, transparent and trustworthy.

Until the last few years, science communication was generally regulated by lax laws; the words ‘scientifically proven’ were just another tool in the marketer’s kit. Now, however, in a world of misinformation and ever more sophisticated attempts to manipulate consumers, those who use science to sell must contend with highly inquisitive watchdogs in consumer groups, and in leadership. Smart audience members ask questions. Marketing needs to answer them.

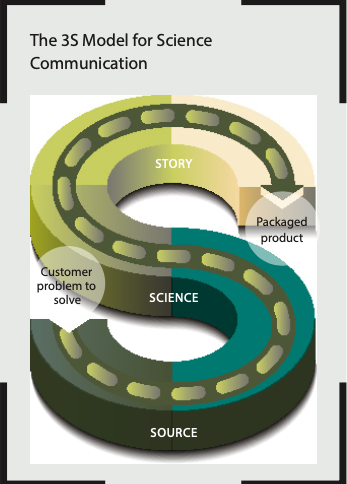

My 3S Model for Science Communication (see graphic below) provides three lines of defence for marketing. Perhaps more importantly, it offers three lines of inquiry for consumers.

The Story

All good science communication requires a great story. Recent research from Jennifer Aaker at Stanford Business School suggests that consumers are at least ten times more likely to remember a story than a fact. Stories allow us to attach emotion and relevancy to information. Stories are a marketer’s bread-and-butter.

The traditional marketer’s story is like the top of a pyramid – the most narrow and sculpted view, that shocks and awes, and almost always features in annual reports and Instagram posts. But a narrative, emotional approach does not typically work when using scientific insights: when customers dig a little deeper, they regularly discover the pyramid is hollow.

Consider the example of moisturizer. A glittering video advert flickers into view. A nipped and tucked woman you vaguely recognize from a 1990s movie strolls along a coastline, promising that the secrets of the sea allow her to look 20 years younger. She tells you that a new, perfumed algae moisturizer is the answer. Go, buy this product, she urges.

The algae moisturizer advert will get a lot of attention. The company has spent money on the location, the branding, the spokesperson. But there are two significant questions that the discerning audience member will – and should – raise.

The Science

The first question is: how will this product deliver what it promises? The Science portion of a claim addresses this question by educating customers to understand its underlying mechanism of action. For the algae moisturizer, the discerning customer should be able to read on a brand’s website how a particular ingredient helps the skin: exactly how will topical algae make me look younger? Knowing how it works, is this the most effective version of this product for me?

Similarly, a consumer may ask, how does the added calcium in oat milk benefit my body? How did you arrive at the figure in the report? How does this vaccine actually work? For a reputable seller, educating the customer is the ultimate win-win. Do you remember the last time you needed dental work? A good provider would walk you through the procedure step-by-step, explaining the possible side effects and interactions with other factors. This kind of personalized education experience is essential to building trust between the provider and customer.

Brands are developing increasingly creative strategies to achieve that effect: free online workshops with experts, panel discussions with members of the team, and try-before-you-buy services. Internal communications teams and business partners, too, are working on educating their internal customers, with training courses in data literacy and fields related to the product.

Getting the Science part of the model right builds customer loyalty. It says: “We’re on your side, and we’re here to help you”. It also benefits society, filling in gaps in consumer education and helping them make more informed decisions that suit them and meet their needs.

The Source

The second question the consumer may ask is: “What does that small print say?” Consumers want to know the truth behind the numbers. They want to know about the scientists, the test subjects, the ethics. They want to know the Source.

The Source provides the core truth that can be probed, tested and examined from every angle. It should be the diamond at the centre of the crown, unassailable and unmalleable, even under extreme pressure. The Source might originate from a well-resourced research and development team, an outsourced specialist group, academic research or even a well-cited paper from a significant, reputable peer-reviewed journal.

The Source is an ethical requirement – and in some instances, a legal requirement – for any product that leads with scientific storytelling. It also shows that a seller has nothing sinister to hide, and, in the case of a Source that comes from an exceptionally talented or innovative team, it may even provide a new selling point.

The Solution

Shaped like an ‘S’, the model implies that the Source, Science and Story are seamlessly linked. One should always lead to the other, frictionless. Just as a consumer’s need is best addressed at the Source in order to produce a valuable product, the end-product must directly connect back through the Science to the insight at its core.

Traditional marketing stories allow for flaws. Telling stories with science in the 21st century leaves no room for error – or lies.