Everyone wins, including men, when feminine leadership behaviours take centre stage

If someone said that you “negotiate like a woman”, what would you think? Would you think they meant you were too emotional? Would you take it as an insult, insinuating that women are no good at negotiation? Negotiation has historically been a masculine game played in a business world built by men, for men.

But the times, they are a-changin’. As nations, governments, businesses, communities and individuals struggle to identify potential paths forward amid massive uncertainty in a world wracked by a pandemic and its economic and psychological fallout, it has become clear that the masculine ‘my way or the highway’ approach to leading and collaborating with others is no longer serving us. Whether it’s US states (or national governments globally) struggling to procure PPE, businesses renegotiating leases, or parents figuring out who will homeschool the kids, we need a more sustainable approach to resolving conflicts – one that expands the pie and preserves partnership through consensus-building.

In this time of great stress and uncertainty, negotiators could benefit from incorporating more ‘feminine’ characteristics. It is an approach that’s already working for some world leaders. It’s no coincidence that many of the countries which have had the greatest success in managing the Covid-19 pandemic, such as New Zealand, Taiwan, and Germany, are run by women. And yet, women still only represent 7% of the world’s national leaders. Some suggest success in this context can be attributed to an approach that is characterized by immediate action – San Francisco mayor London Breed, a woman, took action before the California state governor or Los Angeles mayor, both men – as well as empathy, a sense of community (including listening to others), and the habit of service and coming to one another’s aid. Broadly put, when leaders or negotiators focus on others, tell the truth, and engage others to partner with them to solve conflicts encircling the community, it engenders trust and a willingness to subjugate personal goals in support of superordinate goals which ultimately benefit all parties.

Stereotypes versus actual performance

Changing our views of what it means to apply a ‘feminine’ approach to leading and negotiating, and thereby accepting and celebrating a more balanced approach, will take work. Many people – as young as early elementary school children – have stereotyped views of female and male occupations (click here for a short, powerful demonstration of this on YouTube). Humans suffer from confirmation bias: even when confronted with data to the contrary, we will search for, favour, and recall information that confirms our personal beliefs or values. Exposure to data, as well as training to recognize and overcome bias, can help change views. For example, one study from the Pew Research Center (Women and Leadership, 2015) found that men receive higher marks for ‘being leaders’ than women, despite respondents ranking women as either equal or superior to men on seven of eight leadership traits. Those traits included honesty: outside the 64% who said there was no difference, 31% said women were more honest than men, and only 3% said men were more honest than women. Respondents indicated that men and women make equally good political leaders: but among those who suggested there were differences in working out compromises (about 45%), most said women (34%) were better than men (9%).

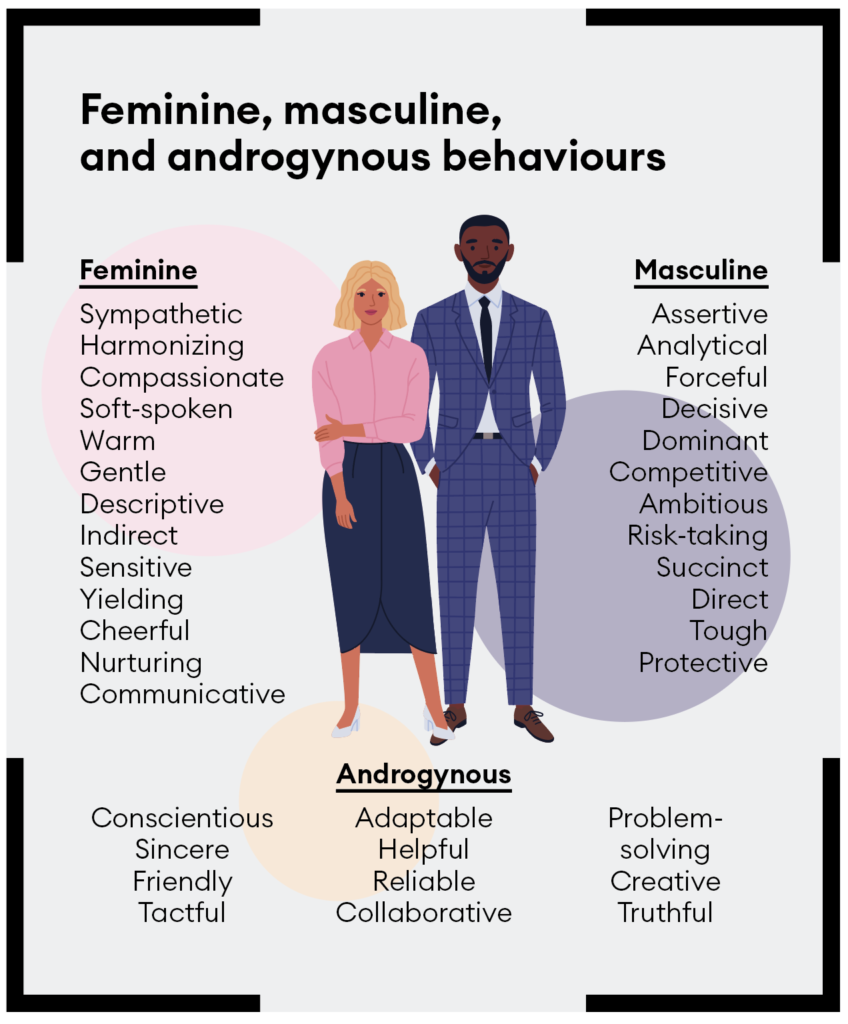

Whether this has to do with one’s sex or gender is unclear from this study, but when we compare gender-based traits we can see how ‘feminine’ behaviours – being compassionate, harmonizing and communicative – can facilitate compromise and resolution of conflicts, whereas forceful, assertive and dominant (i.e. ‘masculine’) behaviours may stall agreement and damage relationships. That particularly matters when we consider negotiation more broadly and sustainably, rather than just in terms of one-off transactions; it’s clear that the relationship between negotiating parties can be as important as the terms of an agreement. For both women and men, the feminine behaviours that make us better leaders also make us better negotiators.

Rewriting the rules

Research on gender differences in negotiation demonstrates that compared to men, women tend to be collaborative, integrative, communal, and focused on the long term. What if members of society started to catch up with women’s actual performance and interpreted ‘negotiating like a woman’ as something positive? What if instead of trying to shape women to become more assertive, decisive and competitive, we rewrite the rules, suggesting that both women and men adopt a more feminine approach – or at least, consider a more gender-neutral negotiation style? By adopting behaviours that are traditionally masculine, and those that are traditionally feminine – as well as those that are androgynous (see below) – negotiators can effectively enhance trust and build creative and collaborative conversations.

What is our advice to negotiators? Embrace this new, post-Covid norm. First, don’t try to be a man (who is socialized to use competitive and aggressive tactics to win). We need to help each other, not reinforce the mentality that in a male-dominated business world, there can only be one winner. Women especially should embrace their inclination to collaborate rather than compete, be authentic in playing to their strengths, and mutually support other women – after all, we have far more to gain by lifting each other up than by holding each other back. Don’t be afraid to demonstrate empathy. Embrace collaboration and the collective good. Choose to be a role model, showing compassion and care for others.

We encourage both women and men to embrace this new normal for how to be effective negotiators in the 21st century.

Collaborate rather than compete

Research supports the idea that men tend to be more interested in wielding power at work than women, who prefer winning through influence. Women are expected to be communal and warm. Collaboration and looking out for the common good are approaches often neglected in a more masculine, winner-takes-all approach to negotiation. We know that leveraging informal networks through relationship-building is an effective strategy for women in the office, but it works in the negotiation space as well.

One of us had a job negotiation experience where two companies were vying for her. Rather than pitting the two companies against each other and holding her cards tightly, she and the two recruiters instead chose open, transparent communication with the shared goal of wanting the best outcome for all parties. She kept both recruiters in the know as she advanced through the process, sharing details about what each company was offering and decision deadlines.

Both recruiters appreciated the candid communication, which allowed them to confidently raise their offer package and provide flexibility with timelines. This led to a higher base salary, the most desirable aspects of one job description being written into the other, and even a sincere “good luck” from one recruiter as the candidate headed off to visit the other. Although she eventually had to let one of these companies down, the positive candidate experience resulted in an open door for future employment opportunities at this company, as everyone parted on great terms.

Be authentic

It’s tempting to focus on the ways in which men and women are different from one another in negotiations, backed up as they are by the research evidence. Yet men and women are not monolithic groups. All of us have had women colleagues who can beat their chest alongside the men in her group without missing a beat. For some women, that kind of behaviour may come naturally, and it enables them to persist and succeed in highly competitive situations. For other women, expressing vulnerability – a trait that comes more naturally to many – is key to engendering trust and extracting information from opponents, which are also important skills in negotiations.

Increasingly, research has shown that authenticity – bringing our ‘true’ self to work, including negotiations – leads to greater gains than suppressing aspects of our identities that do not confirm to stereotypes. Simply put, it’s better to play to your strengths than to try to transform yourself into someone you’re not.

Mutually support other women

When it comes to negotiating in team settings – such as representing your division or advocating for resources – we recommend embracing the spirit of non-competition and looking for opportunities to support others, especially other women. Women are already at a disadvantage when it comes to negotiating, whether being penalized for violating societal norms, or refraining from negotiating altogether. You can help to balance the uneven playing field that women face by intentionally enhancing other women’s presence and effectiveness in three ways: platforming, amplifying and facilitating.

First, where appropriate, introduce female counterparts (or even opponents) in the way you’d like to be introduced. By platforming – sharing a colleague’s expertise, experience or accomplishments – we provide others with a step up and boost credibility, which is key in negotiations. This is important because many women opt to ‘let their capabilities speak for themselves’, avoiding bragging or boasting (an unfeminine behaviour). They prefer to be introduced by others: “Jane has spent 20 years in commercial real estate and has been named a top producer for the last five years.”

Second, use amplification to help others refocus on a woman’s inputs when they’re ignored, discounted, or repeated by another who would take the credit. Amplifying is a strategy recommended to male allies, but women should similarly embrace this strategy to support their workplace ‘sisters’. Try formulations such as “Like Jill said, I think it’s a good idea that we…” Correct others when credit is mis-attributed and restate another woman’s point when it is interrupted or ignored.

Finally, use facilitation or group process skills to check and ensure other women’s ideas and concerns are voiced and addressed. Facilitating – attending to group dynamics in ways that improve how a group of people interacts – can help. You may need to temper an over-participator, ensure all members are heard, and check for agreement when silence or non-verbal behaviour might obscure true feelings. This is particularly important because silence may indicate a woman’s fear, reticence, lack of confidence, or frustration. Consider: “Jessica, I noticed that you were quiet when we were discussing this. Might you be willing to share your thoughts?” Engaging in these behaviours provides a model that begs reciprocity, ultimately building goodwill and the community of women. It also helps you become more successful (see S Zalis, ‘Power Of The Pack: Women Who Support Women Are More Successful’, Forbes.com, 2019).

These tactics could work for men, too. The leadership traits that people say they most appreciate, that they want in a leader, and which make a successful leader, are the positive traits most likely to be attributed to women, not men: traits such as being humble, compassionate and collaborative. We all have something to gain by negotiating more like a woman.