Corporate fear of failure and uncertainty kills innovation. Leaders need to rethink how they handle risk

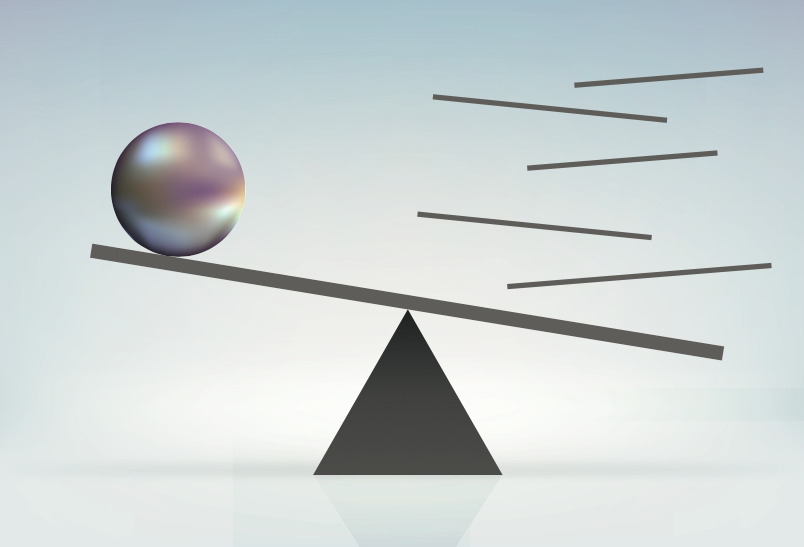

There is a complex inverse relationship between the risk appetite of an organization and how it factors innovation into its competitive strategy. We often hear the old adage ‘No risk, no return’, acknowledging that innovation is essential to giving customers what they want. However, when it comes time to put strategic initiatives into action, many organizations pause to contemplate the numerous risk factors. It is a hesitation that can be fatal to innovation: in many cases, systematically contemplating a project’s risks results in reductions to its scope, budget or resources. But all innovations carry a degree of risk. It is a question of balance. But in many organizations, the risk/innovation equation has become lopsided – and needs to be rebalanced.

The rise of risk-management bureaucracy

Multiple crises over the past 20 years – the dotcom boom and bust, the 2008 crash, Covid-19 – have ensured that risk management is in vogue. Operational risk, market risk, systemic risks, supply chain risk, political risk, environmental risk, legal risk: the list seems endless. Yet there is also a risk in listening to all the risks in risk management. Management teams begin to overthink the permutations. If we spent as much time thinking about how to innovate and implement, we would have reduced risks to start with.

Corporate fear of the unknown creates a culture of risk aversion which ultimately takes the form of layers of rules, operational guidelines and procedures: of bureaucracy. It evolves almost organically. An organization is typically created around a single product, service or purpose. As it matures, it creates streams of activities which are labelled as processes. Over time, it develops additional processes to support the main activity.

Complexity grows in line with the number of personnel, products, order volumes and activities generated by new opportunities. Yet most organizations create policies and procedures not to be more efficient, but to prevent people from making stupid mistakes. A certain degree of bureaucracy is natural – but left unchecked, it can become a permanent brake on the organization’s ability to move at pace.

One large long-established company in the UK experiencing reduced demand realized that delays in product innovation were the result of leaders over-analysing the risk equation. The head of innovation said, “The easiest way to kill a technology project is to give it to the risk department for an evaluation.”

No wonder. In many cases, speed to market is crucial. If there is no underlying value in hesitation, it should be avoided. This is especially true in relation to technological innovation, because all technology is transitory: it will ultimately be replaced by another technology. The first question in assessing technology should be: when will this technology be obsolete? Technological innovation only ever provides a temporary competitive advantage (and unless you are making it, your competitors can purchase the same technology). Speed is key. The value of technology lies in how quickly and effectively you apply it.

Risk management for all

The reality is that all innovation carries some level of risk and some degree of return. Balancing the equation can mean the difference between extreme profits and bankruptcy. Yet executive teams’ risk appetites and innovation postures are not always equal.

Elements of risk management need to be incorporated into everyone’s job. Imagine playing soccer and having to consult the risk management team on the side-lines every time you needed to kick the ball. Empowering the organization should start with pushing aspects of risk management into everyone’s day-to-day activities, through the right tools, techniques and feedback mechanisms. A mechanism similar to a radar screen can help assess risk factors, dividing risk into factors within the organization’s control, and outside it; and factors that are known, and the unknown. Such a mechanism can be used to help individuals make risk management part of their responsibilities. Meanwhile, the risk management function should refocus on the exceptions and anomalies that emerge from externalities and unforeseen exceptions.

Your risk appetite

Since time is a key competitive element in innovation, senior teams need to learn to assess risk quickly, and to fail fast. Typically, however, senior managers want to avoid failure. If an innovation project isn’t on track, the first reaction is to increase resources. When it gets into deeper trouble, fear of failure propels the manager into even greater commitments. Instead, the manager needs feedback mechanisms to understand when a project needs rapid corrective action. They need to ask a fundamental question: “Have conditions changed, and does this still make sense?”

Unfortunately, the skill of quick decision-making is becoming a lost art. A bad decision is better than no decision, as a bad decision can be corrected; no decision accelerates stagnation and is often a symptom of a bureaucratic process. Managing risk and balancing the innovation equation is a state of mind. Senior leadership need to set the tone and the pace of innovation. Is the organization an early adopter, first to market, or a fast follower?

Having set the tone, leaders need to create the conditions for success. Empower people with simple tools and techniques to make risk management a part of everyone’s job. Reduce the natural tendency to build bureaucratic processes by emphasizing communications and collaboration. Establish an environment to foster creativity and experimentation. Define metrics for people engaged in innovating to gauge progress toward ‘Go/No go’ decision points. Be prepared to change direction, at pace, when conditions change.

If an organization’s fear of failure outweighs its appetite for risk, it will find that innovation has been happening at its competitor – or that the door has been opened to new competitors. Organizations cannot afford to ignore risk, but nor can they afford it to be a permanent constraint on the speed of innovation. It’s time to rebalance the equation.